Local Color

John Haberin New York City

Archibald Motley, Folk Art, and American Modernism

Could America's most overlooked folk artist have had serious academic training? Archibald Motley took pride in his skill. At his best, though, he throws caution to the winds, packing his canvases with local color. Meanwhile, for the American Folk Art Museum, it took folk art and Modernism to sustain each other. But was there a distinctively American Modernism—or a distinctly modern America?

In truth, Motley was an outsider in exactly one sense: he lived and worked not in New York, but in Chicago and its black community. It is hard to say which of those two locations has done more to keep him or anyone else out of the history books. When the Whitney takes his retrospective as its first loan show ever in its new building, it is making a statement.  He comes as close as anyone to an alternative tradition within Modernism, of a popular art form. Long before Pop Art and the graphic novel, he sought an art about and for the people.

He comes as close as anyone to an alternative tradition within Modernism, of a popular art form. Long before Pop Art and the graphic novel, he sought an art about and for the people.

For the people

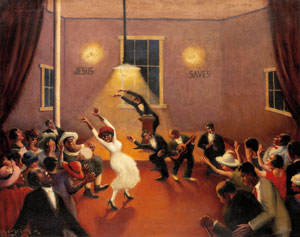

Of course, to Archibald Motley that meant black people, but not without turning a sharp eye on them as well. His paintings from the 1920s and 1930s revel in stereotypes, and they are not pretty. He proclaims them in his titles—Barbecue, Getting' Religion, The Boys in the Back Room. They include the overweight and overindulgent, the country folk and the city slicker, the unholy liar and the Holy Roller in an ecstatic dance. They include big red lips and big white teeth. Were his subjects beyond embarrassment, or was he?

Did he realize that he was feeding the damaging stereotypes himself, and just what was he up to? The Whitney calls its retrospective "Jazz Age Modernist," but Motley was never fully at home with Modernism. Born in 1891, he studied at the school of the Art Institute of Chicago, and he went to Paris in 1929 thanks to a Guggenheim Fellowship. He was not in search of Pablo Picasso and not about to drop in on Gertrude and Leo Stein. No, he was again heading for the action, to him all but indistinguishable from late nights in Chicago. He could not help noticing, too, the black doorman at the Jockey Club.

Had Paris made a difference, with its early jazz rhythms? Had it brought him to the brink of a uniquely American Surrealism, like others in New York? Had it brought him closer in spirit to Romare Bearden in collage and abstraction, James Van Der Zee, Winold Reiss, and the Harlem Renaissance that he never really knew? Or had it only confirmed his apartness? Did it lead him despite himself to a genuine outsider art? Or did it only confirm the academic beginnings that he could never quite leave behind?

The curator, Richard J. Powell of Duke University, proceeds by theme—a museum fashion that risks obliterating an artist's character along with chronology. It works well enough for a small show and a short career. Almost everything falls within a decade, starting just before Motley's departure for Paris, and it quits, as did he, well before his death in 1981. It also bodes well for the Whitney's new home, where it fills the smallest of four levels for exhibitions. Will the bulky Renzo Piano architecture dwarf the barely forty paintings, will its walls look silly painted with the dark colors of an earlier age, and will the skylit rooms fail to keep up with changing weather? No, no, and no again.

Yet it also works because the themes supply their own chronology—from Chicago to Paris and back, plus Mexico in the 1950s, but opening with portraiture. A self-portrait from 1920 has Motley as obsessed with style as with painting, in a pencil mustache and horseshoe tiepin. It is also as stiff as the surrounding walls. A later self-portrait gives him the beret and stance of a proper bohemian, but still obsessed with his brushes and fine art. Only a serious artist, it seems to say, would pose next to classical sculpture while a woman comes to life on his easel, as in the myth of Pygmalion for Tom Anholt. The wall behind him also bears a cross, and this Roman Catholic will keep moralizing among the evangelicals and the heathen.

The painting within a painting is of his wife, who was white—and other portraits cover a range of skin tones, their titles taking care to identify the "mulatress" and the "octaroon." A grandmother has her humble habits. A "cultured lady" and Chicago's first black art dealer share something greater still. The artist who went by the name Archibald J. Motley, Jr., is concerned for virtue, education, high style, and the entirety of blackness. The range will appear in all his work, and pride will war with all that it must embrace. The portraits never get past the leaden realism of the Ashcan school, but something else is still at stake.

Leaping over Modernism

That something kicks in around 1929, and it translates into tenser and more delirious art. On the one hand, he is celebrating the energy of a community. He liked to say that he hung out in pool halls and dance halls to "study all the characters." He packs his canvases with them, in overlapping layers and stories. In one painting, a pool table tilts sharply upward, but this is not Man Ray, his pool table receding into a breathtaking Surrealist sky. It merely allows Motley to leave out nothing, not least the easy jokes and the action.

On the other hand, Motley is documenting the strains within a community. Yet the tensions lie not just within Chicago's "black belt," but also within him. Unlike Jacob Lawrence, he rarely depicts the Great Migration, the flight from the American South, or the American struggle explicitly—the fearful, dangerous course of African Americans from the South. When he does, as Town of Hope, he omits neither a cloudy sky nor an equally symbolic ray of light. More often, though, the strains of migration appear in his attention to social hierarchies, from the decorous ladies of the "old settlers" in Cocktails to a wilder and raunchier Saturday Night. He has equal sympathy and equal scorn for both.

Colors intensify, with acid purples in contrast to still more acrid reds. They add their own jazz rhythms, greens rippling from women's skirts to drawn curtains. More startling, they may soak into a canvas almost like spray paint. They allow the action to pierce more deeply and strangely into the canvas as well.  Horizons sometimes drop away entirely, as a car drives directly into the light. More than ever, Motley seems most at home in the night.

Horizons sometimes drop away entirely, as a car drives directly into the light. More than ever, Motley seems most at home in the night.

As Motley breaks free, he begins to identify with something less decorous, with his eye first and foremost on people. Yet he carries with him the sense of virtue and unease—and knowledge that even a black who need apologize for nothing remains an outsider in America. Even then, he can never quite encounter Modernism, at least on its own terms. He can only leap over it, to something more akin to folk art. It appears in the caricatures and the colors. It allows him to abandon academic realism without abandoning his people.

The search for a popular art dogged others before World War II, too. Critics who claim outsider art as an influence on the American modern miss the real story. The American Scene of Grant Wood and Thomas Hart Benton declares a folk realism, like Motley's goat that might pass for a unicorn with two horns, while creating American myths. So does a more modernist city for Edward Hopper—like Motley's, abolishing the border between day and night. As Langston Hughes wrote of Chicago, "midnight was like day." The wine here never stops flowing, and a well-dressed waiter is always on hand to deliver it.

Motley cannot tune out the pimps and the whores, but neither can he stop himself from wanting to live among them. Here Sunday in the Park becomes a parade of fancy horses and balloons, and a carnival in art is always in progress. His farewell work, his one direct commentary on racism, brings him closer still to myth. The packed canvas, which took him nearly ten years ending in 1972, depicts one hundred years of freedom as a compendium of the Klan, a lynching, a burning cross, and the devil himself. The disembodied head of Martin Luther King, Jr., floats before a building out of gothic fiction and an icy blue sky. Banners for racism and radicalism belong to a decade that a jazz age modernist could never really know.

Folk music

Modernism in America had many beginnings—more than a few of them in Europe. The triumph of American painting, in Abstract Expressionist New York, was also a triumph of American immigrants. And few did more to nurture that history than Alfred H. Barr, Jr., the first director of the Museum of Modern Art. Yet the very idea of MoMA, not to mention the cash to back it up, began with Abby Aldrich Rockefeller and two of her friends, Lillie P. Bliss and Mary Quinn Sullivan. (David Rockefeller is still the museum's honorary chair, a post shared with Ronald S. Lauder, a noted collector of Cubism.) And she also founded the Folk Art Museum in Colonial Williamsburg, to preserve a thoroughly American past.

The American Folk Art Museum would like to claim both as kindred spirits, even as MoMA obliterates its traces from midtown. With "Folk Art and American Modernism," it makes a game effort to bring those spirits together. It opens in 1938 with Bernard Karfiol's Music Lesson, and this is one lesson without a teacher. Two boys, one with an accordion and one with a guitar, play out their nascent sexual energy, while a vase in the shape of a hand reaches for its flowers. Do their provocative poses owe more to American Surrealism or to folk portraits above their heads on the wall? To help you decide, the museum has hung two of them to the painting's left.

What does it mean to be modern or an outsider art? The question is everywhere these days, as boundaries fall and genres run together. Maybe they always did, for Modernism can fairly lay claim to the most cosmopolitan art ever, but also an obsession with "the primitive." American folk art is just a part of that obsession. Karfiol was visiting Ogunquit, Maine, for the Summer School of Graphic Arts, established there in 1911. It offered every chance, the show argues, both to experiment and to recover New England traditions.

Maybe, but hold on a minute. Karfiol is a mere footnote to Modernism, as forgotten as the artists that he quotes. Besides, his very quotation underscores his break with folk tradition. The colorful boys have way more to do with Balthus than with the prim characters up on the wall, dressed in black and white. The curators, Elizabeth Stillinger and Ruth Wolfe, are not out to overturn modern art's primacy, although they include their share of provocations, too—such as Mary Ann Wilson's almost surreal mermaid from 1815 and Oliver Wright's stiff but sophisticated portrait of a stiff but sophisticated Massachusetts gentleman. Rather, they are documenting the dissemination of folk art in America.

They see Modernism as essential to that dissemination. Sure, the story includes modern artists, but almost as an afterthought. Charles Sheeler uses the clean lines of Shaker furniture for his 1926 interior, like Cubism before the letter. Marguerite and William Zorach prefer instead the brute outlines of old toys, as inspiration for their sculpture. Elie Nadelman points in both directions, with his own music lesson, with the delicate craft of carving in wood. However did the Whitney call its 2003 Nadelman retrospective "Sculptor of Modern Life"?

Mostly, though, modern artists lie buried amid the usual litany of folk art and its collectors. Besides Rockefeller, they include Edith Gregor Halpert, with her American Folk Art Gallery, and Juliana Force at the Whitney Studio Club—the predecessor of Whitney Museum of American Art. (Try to savor the irony that the Whitney later sold off its design collection.) The well-known weather vanes in the form of the archangel Gabriel even sprang from a corporation, Gould and Hazlett. The show raises contemporary questions all the same, starting with outsider art that has little to do with madness. When Fernand Léger fell in love with Peaceable Kingdom, by Edwards Hicks, had he discovered an alternative to Europe ravaged by war—or a place for European visions in America?

Archibald Motley ran at The Whitney Museum of American Art through January 17, 2016, "Folk Art and American Modernism" at the American Folk Art Museum through September 27, 2015.