Playing to a Full House

John Haberin New York City

The Whitney's Collection at 75

Stuck in town for the Fourth of July? You could find a far worse celebration of America than the Whitney Museum's celebration of itself. For its seventy-fifth anniversary, the museum has given over every floor to its permanent collection. It boasts of seventy-five years devoted to collecting, displaying, and attempting to define American art.

"Full House" also allows one to pore over the building—itself just turned forty—from top to bottom, before a planned expansion by Renzo Piano. An unusually open arrangement of Marcel Breuer's movable walls helps bring out a forbidding structure's spaciousness. The curators even create a dead end merely, so far as I can see, to let one contemplate a trapezoidal window. It works.

The Whitney offers a singular view of American art, assimilating an entire century into three postwar movements—Abstract Expressionism, Pop Art, and Minimalism. Each has a full floor, in three separate but parallel exhibitions, but with Michael Heizer spilling out of the basement. The top floor adds a fourth exhibition, for Edward Hopper alone, with a handful of loans that help a signature American artist stand alone. Moreover, "Full House" reinterprets each of these in light of work closer to today. It makes art a matter of give and take among artists, with the most critical voices closest to the present. As at most birthday parties, the hosts want you to root for the years to come.

Starting over

The collection. Yawn. And a war-horse like Edward Hopper? I could all but hear the collective deep breathing at a preview, which uncharacteristically emptied out almost as soon as the chief curator had her say. The press could have been rushing off for the long weekend even on a Tuesday, leaving a less than full house. See, you can be smarter than critics.

I can understand some skepticism. Museums these days are in the habit of perpetually reinventing themselves—the story of an anniversary exhibition on "Making the Met." MoMA QNS has come and gone from Queens, and the Modern's own collection now almost takes a back seat to its new home. The Whitney is about to expand for the second time since I began this webzine—with a new home designed by Renzo Piano south of Chelsea and another rehanging as "Where We Are."

I have missed the permanent holdings, which have ceded space to other shows, such as the American entry from the Venice Biennale. After all, I pretty much learned twentieth-century American art here, especially prewar art. However, enough old news, one might complain, and what critic would dare review the collection? Besides, the Whitney let it all hang out in two dismal exhibitions, termed "The American Century," barely six years ago. Like perhaps everyone but the state of Florida, it was using the millennium as the occasion for self-examination—or maybe self-flagellation.

For the very same reasons, however, it makes sense for both the museum and visitors, too, to start over—to look hard at the collection, now. When the Whitney added fifth-floor galleries in 1998, it split the permanent display over two floors. It took some chances, such as placing a haunting self-portrait of Arshile Gorky as a child with the older half. However, rather than shake things up, it stifled art all over again. The odd view of Gorky promised more frequent shifts that never took place. The noncontiguous floors have made the divisions between the Whitney's early Modernism and America's emergence on the world stage more rigid than ever.

After the millennium exhibitions, the collection deserves another chance that much more. Each half reduced art to cheerleading for that grand old "American century" and, worse, to a document of changing cultural fashions. One decade after another paraded past, each era as empty of conflict and resonance as the last. The finale played out before a rock 'n' roll beat, as if to confirm the doubts of David Hickey that art has enough popular impact. One could imagine jazz without Abstract Expressionism, Hickey notes, but hardly the other way around. A pity that Willem de Kooning painted while whistling Mozart.

In a traditional museum, art advances in small chunks, like figures in a textbook or works at auction. At the millennium, art became another kind of illustration, this time for cultural theory. The Modern's millennial exhibitions took a thematic approach even further: it dropped chronology completely, and the themes went from oppressive to empty. But then MoMA, too, is struggling to reconcile its history with its engagement in the present.

Lost innocence

"Full House" does not simply change curators and theses. It departs from a strictly chronological or thematic presentation. The floors center around recognized movements within art history, but they play out in unaccustomed ways. Each movement, focused largely on the 1950s and 1960s, seems to confirm a conventional narrative of the triumph of American painting, with upbeat titles like "The Pure Products of America Go Crazy" for Pop. The 2006 Biennial, which stressed European imports and the cultural underground of the 1970s, sounds downright cutting edge by comparison. Ah, but then things get interesting.

It starts innocently enough, or does it? One cannot banish Calder's Circus from New York, any more than one can banish tourism, but one passes it quickly on the way upstairs. Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney still greets one first thing, seductive and fiercely independent as ever in Robert Henri's portrait—but half hidden in the lobby, behind one's back as one heads for the elevators. Has the Whitney turned its back on its own origins, from the Ashcan school of George Bellows to the circle of Alfred Stieglitz after The Steerage? One sees less than usual of these and others of the old school. When the Modern's Alfred Barr represented America at the 1950 Biennale with young abstract painters, for example, he also invited John Marin, but the Whitney does not, and he could stand for many.

Each floor begins comfortably as well. The three main exhibitions all center on a large, open gallery. The big names of Abstract Expressionism do not often look so ample and stately side by side—or side by side with Robert Rauschenberg, even at his most painterly. The Modern, with its odd sightlines and single-minded attention to Jackson Pollock, might learn something. The Modern could gain more often, too, from the effective integration here of photography. As seen by William Klein and Helen Levitt, "action painting" comports just fine with the action on New York City streets. The three central rooms become just a little less symmetric with each floor, in deference to the shifts from formalism to pop culture and finally to Minimalism's interaction with a gallery itself.

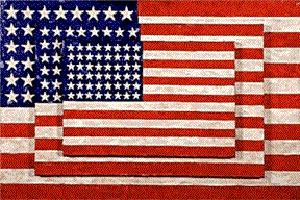

Artists like Charles Burchfield get only a single work, but someone as capacious as Jasper Johns may appear on successive floors—his Three Flags as Pop Art and his White Target, in fact painted the year before, as Minimalist (and the Whitney itself will host Jasper Johns in retrospective coming up). Each floor also pauses for one or two concentrations on an artist, off to the side. Louise Bourgeois gets unaccustomed attention within Abstract Expressionism, and Pop Art looks way back to Jacob Lawrence for his War Series. Ad Reinhardt has his own room, so that Reinhardt's shades of black can slowly unfold. The show does not make a revisionist fuss about recovering lost reputations, although the second floor has room, say, for Ann Hamilton and the third for films by Jack Goldstein. Robert Watts made his Case of Eggs (actually plastic and wax) back in 1964, around when the black artist tried to copyright "Pop Art," and it looks hilarious next to Andy Warhol and Warhol's Brillo Boxes.

When later art slips in, it mostly dates from a flurry of the ironic detachment nearly twenty years ago. Cindy Sherman, Richard Prince, Laurie Simmons, and David Salle appear, all with early work. I shall graciously overlook the trendier inclusion of Elizabeth Peyton. Fans of cluttered installations, performance, or new media can pretty much forget it. Aside from classic videos by Stan Brakhage and Mary Kelly, I recall an endearing, if not terribly profound montage of B movies by Christian Marclay and a wildly funny sermon on The Holy Artwork by Christian Jankowski—delivered by an actual televangelist.

Like the sermon, then, the show seems to speak to American art's lost innocence. At half the size of "The American Century," it may seem uninterested in summing up all that history—or the Whitney's own. It may seem a curious birthday gift, although a glorious package. However, you surely have noted already some unexpected inclusions and even more unexpected juxtapositions. And they start the very moment one steps onto the second floor. Entering that enormous space for Abstract Expressionism, I caught Georgia O'Keeffe out of the corner of one eye. Fortunately, surprises like this add up.

The critical impulse

Does "Full House" stack the deck? Throughout, it brings prewar art into postwar contexts. As with O'Keeffe, one sees this most as one first turns from the central, facing wall. Stuart Davis leads the way to Pop Art. Minimalism's industrial materials manage to include bridges, factories, and skyscrapers, as evoked by Charles Sheeler, Charles Demuth, Lyonel Feininger, Joseph Stella, and Man Ray.

Still further to the side, as the rooms grow smaller, more recent decades appear. Abstract Expressionism ends with the manic performances of Paul McCarthy. Along with Postmodernism in photography and Lawrence's sorrow at racism and war, Pop Art extends to Hollywood Africans by Jean-Michel Basquiat, gay pride from Félix Gonzáles-Torres and David Wojnarowicz, and the Robert Mapplethorpe photo of a torn and beaten American flag. Minimalism proceeds by stages from Tony Smith and his big, black cube to Jacqueline Winsor's mysterious smaller one, on its way to a cross between an afro and a spider by David Hammons.

"Full House" wants the positive message of an American century, defined as a time when America set the rules for art. However, it also wants you to wonder just how well you know the rules. Each floor defines its movement not so much by concept as by conflict. Within Abstract Expressionism, one moves from O'Keeffe's intimations of the unchanging sublime to McCarthy's, Bourgeois's, or Levitt's awareness of the transient and physical. Pop Art moves from seizing a moment in mass culture to appropriating mass media, from Warhol's cheerful acceptance to Lawrence's mournful refusal. Minimalism has its basis in both the industrial city and the human body.

The polarities do more than leave art's meaning open-ended. First, they link a work of art's presence not to its formal autonomy, but to something felt and something human. If Kelly's massaging her pregnant belly, Winsor's unseen interior space, Robert Mapplethorpe in a final self-portrait, or Hammons's blackness do not seem intimate enough, Minimalism has room for a Claes Oldenburg bedroom set. One experiences even Reinhardt's blackness as a physical awakening. Second, they suggest that art has become ever more inclusive, ever closer to a "full house." At the same time, it has become more ironic, angry, and political.

As one moves away from a floor's center, one decenters a view of America as male, white, and straight. Even an Edward Hopper retrospective makes him a living influence on diverse stories today, far from the backward-looking self-portraits of his youth that one encounters first. It shows him becoming the painter of light, from Paris to the shores of America, but also as a young magazine illustrator of trash fiction and inner lives. His later women partake of both. Isolated in city nights and suburban balconies, movie houses and hotel lobbies, lonely bedrooms and their own nakedness, they cling to light and shadow as if for protection from their inmost desires. From there, the Whitney descends easily to The Ballad of Sexual Dependency, by Nan Goldin but a title that could apply to Donna Ferrato and so many others, playing on the mezzanine.

Loneliness, shadow, and sexual dependency—that does not exactly end on a sunny note. Yet the Whitney offers an optimistic survey indeed of American art. I not mean its nostalgia for great decades past, although that helps. Rather, I mean its trust that art over time has become more vital, more welcoming, and also more critical in spirit. Art here does not blame dead white males, but it still learns from them, laughs at them, and fires back on terms they could never have imagined. If "Full House" truly encompassed contemporary art, could it retain that confidence?

A postscript: out of house

Michael Heizer pushes well past confidence, to delusions grandeur. As part of "Full House," he is reaching for eternity. First, however, he will have to escape the museum's survey of modern American art. But where exactly does "Full House" begin and end?

One could argue whether to count the lobby, which lacks the Biennial's overflow of art to the stairwells and beside the elevators. Robert Henri's portrait of Whitney herself or Calder's Circus, each sited alone, lacks the playful contexts, confrontations, and themes that enliven the floors above. They may serve as a tasteful greeting, or they may merely get the inevitable out of the way. The full top floor for Hopper has a sparkling rejoinder from contemporary artists, but set off on the mezzanine. I like to count all these as part of the Whitney's spirited game, but either way they work. Not so for the courtyard downstairs.

Heizer's sculptures respond to nothing outside themselves—not the visitor, who cannot circulate between them, not the museum castle's formidable moat, and not, for that matter, to each other. The space almost always presents a lost opportunity. It resides simultaneously inside the museum and out, enclosed by high walls and yet visible from above as one enters, part of a museum but adjacent to public areas for shopping and eating, potentially barring no one and yet requiring a seeming drawbridge above to the museum's entrance. All these limits beg for an artist to challenge the museum's very identity and the art's own. A big group show about interplay, one that puts motion back in the idea of an art "movement," seems just the time to give it a try.

The mournful sunken court isolates sculpture both visually and from a visitor's physical encounter with its space. A great show would use that downstairs as aggressively as Marcel Breuer, rather than leave a cafeteria extension forever awaiting an outdoor dining permit—or a dumpster. Imagine if people could circulate in the moat, encountering both confinement and open sky. Imagine if those crossing the unmoving drawbridge above could see people taking their own course below.

Such a confluence of art would have to take up space. It would force visitors to decide whether they even can go outside to enjoy the city's summer sculpture. Heizer attempts neither one. As with far too many courtyard installations here, the cafeteria doors remain shut. He does not even use the south half of the yard. The sculptor has a way of straining both for eternity and for the moment, and here he does both. The work itself looks at once static and above it all, but also ragged and forlorn.

Heizer, perhaps Minimalism's most formidable presence, never exactly welcomes his audience. A companion gallery show rubs in the pretension that much more, since one can hardly overlook the pedestal under apparently the world's largest flint arrowhead. At Dia:Beacon he presents geometric pits into which not even the eye can fully delve, and in his ongoing cities of raw earth out west, he chases premature visitors away. Here the rocky sculpture mimics ancient cultural artifacts or products of the Earth's motion, as jagged and crusty as a primitive tool or cooled lava. They look too large to take them literally but also too small to invoke a human or superhuman presence. In fact, they resemble nothing so much as sculpture.

"Full House: Views of the Whitney's Collection at 75" ran through September 3, 2006, at The Whitney Museum of American Art. Michael Heizer's latest sculpture also appeared at PaceWildenstein, the second of its Chelsea spaces, through September 23. A related review looks at the museum's focus on its origins and collection in inaugurating the Whitney's new home in May 2015.