A Fine Madness

John Haberin New York City

The Barnes Foundation in Philadelphia

Had I ever been to the Barnes Foundation, a friend asked, and was it musty and fusty? Oh, yes, more than once over the years, and it was. Admirers would not have it any other way.

At least it was in memory, the night before my first visit to its new home, where the mustiness is gone. If sunlight is the best disinfectant, it could hardly remain, in architecture so filled with light. The site alone adds transparency, off Logan Square—an easy walk from Amtrak, City Hall, or the Philadelphia Museum of Art. Strange to say, though, the fuss remains, just as Albert C. Barnes insisted. The building, opened in May 2012, retains his mad view of art. Some would call it a fine madness.

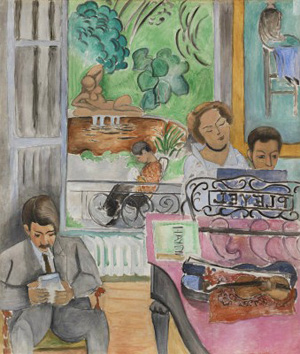

It has his nearly two hundred fleshy Renoirs, but also a show-stopper like Matisse's The Music Lesson. Compared to The Piano Lesson from the year before, it could well stand for the collector's taste. A nearly abstract painting within the painting has moved to one side, a well-dressed man reading has taken its place, and the boy at the piano has lost the shadow in place of an eye. A Matisse sculpture lies beyond the fictive window, as if in the collection's actual surroundings. Most of all, the museum has the "hang," as Barnes liked to call it, that packs and stacks hundreds of works. These are period rooms, with all their limits and all the insight that brings, and the period is early modern art.

Art without distractions

A roomy space for temporary exhibitions tells his story. Born to poverty, Barnes studied chemistry and medicine, married well, and put the money to work, in pharmaceuticals. The opening display includes a product sample, an antiseptic silver compound, although without dwelling on the drug's target, gonorrhea. By the crash of 1929, he had cashed in. He had also, since 1912, been collecting art, guided by a school friend—William J. Glackens, the Aschcan School painter who studied at the conservative Philadelphia Academy of Fine Arts. It was the year before the Armory Show brought Modernism to America, but Glackens headed straight for Paris to find it.

Barnes bought in bulk and quickly took control. Indeed, control could well be his middle name. He was forging not just a collection, but a mission. He befriended Gertrude and Leo Stein and had taken a seminar at Columbia with John Dewey, who helped him see nature on a continuum with experience—and art as the pursuit of both. "For arts that are merely useful," the philosopher wrote, "are not arts but routines; and arts that are merely final are not arts but passive amusements and distractions." Barnes was out not to amuse or to distract, but to teach.

He wrote and taught personally, and the exhibition has a page of his essay questions. Some point to key questions of modern art. "Is art an imitation of nature," and "are there different kinds of imagination?" Others show what he believed art meant for working-class families like his own. "If we are to remain normal, balanced people, what must we do?" It may sound funny to put normal and balanced in the same thought as modernity, but Barnes ran into other contradictions as well.

For one thing, he had an essentially democratic mission, but he could fulfill it only by limiting access. He settled in Merion, a residential suburb, in 1922—and surely not just because the Philadelphia elite refused to take him seriously. For years, only students had access, and to the end the Merion "campus" required reservations two weeks in advance. It was open less than three full days a week, and after his death its neighbors resisted plans to open it more. It also had his unchanging "ensembles" of works and period detail, not unlike Dewey's description of art: "Nothing in it can be altered without altering all."

Barnes stipulated in his will that nothing change. Yet he also left too many problems and too many players. Limited access made it hard to raise money, even as losses grew and the facilities deteriorated. The players included four of five seats on the board set aside for Lincoln University, a pioneering all-black college halfway to Baltimore. The proposed move only added more players, in Philadelphians who demanded proof that they would benefit. Naturally everyone ended up in court.

That part of the story, I assure you, is not on display. Suffice it to say that emotions got out of hand. A devotee made a film madder even than Barnes, picturing the move as a betrayal, and at least one prominent critic, Jed Perl, still sees only a travesty. Others seed instead a wasted opportunity—the chance to create a proper museum, for paintings taken singly, at eye level and in comprehensible order. Both sides feared the mere reproduction of old conditions as kitsch. Not that they had a choice, given the will and the law.

The light box

Within the collection, everything is very much as it was. Rooms follow the old layout, a figure 8 on each of two floors, with mostly low ceilings and molding. A grand entrance room has such signature work as Models by Georges Seurat, whose Circus Sideshow is in New York, and the largest Card Players by Paul Cézanne—one, for good measure, right above the other. Small corner rooms can hold fifty works apiece, with Baroque art amid Modernism and African art amid watercolors. Only The Joy of Life, by Henri Matisse, has moved, from a stairwell to a place of honor on the second floor. Fittingly, one can easily miss it coming off the stairs.

Yet contention gave way to acclaim, from the very opening. In part, this happens when a museum opens. Remember the buzz for the Museum of Modern Art in 2004 or the New Museum on the Bowery? One museum now looks and functions worse than the next. In part, too, critics simply rediscovered the art—like the gloriously clashing colors of a Matisse portrait or The Red Studio, with head scarf and print dress, or a Cézanne still life bursting with flowers. How bad can anyone feel after a day with this collection?

In no small part, though, the architects have pulled it off. Tod Williams and Billie Tsien faced nearly impossible constraints, down to replicating the original site's north-south orientation. One will recognize the elements as well from Louis Kahn, Renzo Piano, and the usual run of contemporary art museums. They include a parking lot lined with trees, water, and walkways. They include a vast and more or less empty atrium, with a restaurant to one side, the collection to the other. They have, however, let in the light.

From the parking lot, three levels of cladding offer subtle variety in the dimensions of the slabs. The update of Brutalism does not look half bad, a useful reminder as the Whitney abandons Marcel Breuer for a new home in the Meatpacking District, designed by Renzo Piano. Above runs the museum's crowning achievement, a "light box" for offices, the length of the building and then some. It cantilevers out from the north, to reveal itself as two levels of glass panels. From the west, along Benjamin Franklin Parkway, the glass disappears, but large windows with wood lattices interrupt the mass. Western exposure signals integration into Philadelphia's museum mile.

It also signals strong but diffuse light, as Barnes would insist. Inside the atrium, the ceiling looks less like a box than a greenhouse with its planes delightfully askew. (The Merion "campus" remains, not only for administration and the library, but also for horticulture—an interest of Barnes's wife.) Both sides of the ceiling tilt inward, but one continues past the other, so that one sees the glow but never the sky. The lighting within the galleries, designed by Fisher Marantz Stone, is mostly artificial. It is just much improved.

The collection looks fresh from the moment one comes in, as if an old layer of varnish had peeled off. One faces three arched windows, with a late Henri Matisse mural above them, anticipating the Matisse cutouts. That rare acceptance of Modernism makes things a little less fusty from the start. And then, turning toward the crush of paintings, one faces the ensembles. The layer has come off not the art, but the hanging and the vision. Perl may miss that vision's peculiar definition of "form," but Barnes at his most controlling should be pleased.

Getting the "hang" of art

To each side of the entrance, an entire wall forms an ensemble. Two pairs of standing nudes, by Pierre-Auguste Renoir, frame the ensemble to one side, standing clothed women the other. A reclining nude tops each ensemble, and other Renoirs lean in from below, with Cézanne and others interspersed. The conversation on the south wall extends to paired saints by Tintoretto beneath paired men by Honoré Daumier. Barnes was boasting of the conversation within and between paintings, including between his contemporaries and past centuries. He was also reconstructing modern art just as, in his eyes, artists were reconstructing painting from within.

Barnes saw himself not as competing with them, but as showing how they did it. Cézanne's Card Players depicts a work of art within a work of art, like an ensemble. Seurat's models pose beside La Grande Jatte, cut off like a picture window. Maybe the same interest led Barnes to El Greco, with church relief sculpture behind a saint, or to a Crucifixion by Gerard David, with the cross to one side and a figure in a cloud to the other. The same puzzle of realism and the visionary led Barnes to Henri Rousseau and to Hieronymus Bosch. And while he collected mostly the French, the puzzle of fine and folk art led to Horace Pippin and Russian icons as well.

The ensembles extend to architecture and décor, chiefly Americana. Cézanne's boy contemplating a skull hangs just above a desk—and his tree-lined alley beside a door. Pipe smokers connect The Card Players to artifacts on the wall and to portraits by Vincent van Gogh. Although all of Cézanne's subjects turn up, including Cézanne's wife, he never appears as a proto-Cubist. Nor, for that matter, does Pablo Picasso. Despite a small example of Analytic Cubism, plus a few more daring works by Giorgio de Chirico and Joan Miró, he is mostly a young man in conversation with Daumier and the past.

One may as well join the conversation. The museum's greater accessibility starts with its new hours and location, where, like the Detroit Institute of Arts and its collection, the Barnes may bring tourist dollars to a beleaguered city. While tickets were sold out at the door, I had no trouble making reservations online over the weekend for a Monday. When I entered, the guard scanned my timed ticket without a lecture that I was ten minutes early. Lines on the floor are enforced, but one can still make the extra effort to catch the only labels—a last name on the frame of each painting. Most rooms have enough printed guides anyway.

Have the layers fallen away, or was memory false all along? The old building was never a fusty mansion (although Barnes lived next door), but an ordinary stone museum, by the architect of the Rodin Museum up Benjamin Franklin Parkway. Conversely, the old limits set in again as the wonder subsides and the spurious connections set in. Most of the old masters are "school of," despite a wonderful early landscape by Titian, with glowing blue and green hills. Proper instruction in art's virtues means a happy family from Edouard Manet, rather than Manet's history and scorn or competition with Edgar Degas, and a young man in a nice blouse by Paul Gauguin or Cézanne's Boy in a Red Vest could easily join the family. Although the collection has more than fifty works each by Picasso and Matisse, one is likely to remember instead too much of Chaim Soutine and Soutine still life or of Jules Pascin. And there is still three or four times as much Pierre-Auguste Renoir and Renoir drawings.

Oddly enough, one can almost appreciate his excess, if not exactly his art. Late Renoir becomes not just a purveyor of flesh or fashionably wealthy pleasures, but a middle-class realist. What one may not appreciate is the wealth of art. Without themes or chronology, one cannot easily run through in one's head or recall what one has seen—although, as Roberta Smith as suggested in The New York Times, the temporary wing could allow invaluable focus exhibitions. People have criticized museum white cubes as institutional, just as they have criticized the Barnes hanging as a holdover from the nineteenth-century Salons. In reality, one has two versions of Modernism as it was coming to be, and I leave it to you to choose your madness.

The Barnes Foundation opened in Philadelphia on May 26, 2012. I first saw it in early July. I quote John Dewey's Experience and Nature (1929).