Feminist Gambits

John Haberin New York City

Griselda Pollock: Avant-Garde Gambits

With the paperback reissue of Vision and Difference, Griselda Pollock's essays are at last widely available. No one interested in feminism or the arts can avoid facing her challenge to art history. I want to introduce her ideas through a shorter, more dogmatic volume, her lecture on Paul Gauguin called Avant-Garde Gambits 1888–1893. Its shrewdness—and even its limitations—will suggest why her cultural criticism has had so great an influence.

Feminist art histories

Among other things, art history explains why some artists have mattered so much. Its weapons are historical categories, such as Modernism, and art interpretation.  The two can hardly be separated: works say something now because of how artists then learned to speak. Works say something, too, because of how anyone today has learned to hear. Artists have long-buried aims and influences, while the present day has freshly buried prejudices.

The two can hardly be separated: works say something now because of how artists then learned to speak. Works say something, too, because of how anyone today has learned to hear. Artists have long-buried aims and influences, while the present day has freshly buried prejudices.

Looking back at the artists' life and times, historians find the reality they represented and the forms they used. Looking at the past and the present, historians find other voices more rarely heard. I mean the voices surrounding artists, the voices that gave them life. I also mean forgotten voices, including women artists, voices that old categories and old clichés exclude. That is why art history takes some training and some work.

A feminist like Pollock finds art history full of exclusions. Why, as Linda Nochlin asked, are there no great women artists? In turn, they find the categories and people, like Modernism or great modern artists, just plain sexist. The artists may remain interesting, but the interpretation of what they did changes. With men, that is likely to mean for the worse.

I hope to argue with Pollock provocatively enough that others will discover her diverse essays for themselves. Even more important, I hope to argue for a feminist criticism with fewer winners and losers. Feminism entails not a new art history, but art histories.

Sure, feminist interpretations can recover women artists and the real women who served as art's subjects. It can even recover them for the female gaze. I shall argue that it also has to rediscover male artists, by revealing the sexual tensions within their work. Anything less reduces art to propaganda. Artists are never simply of their time, or they would long ago have been lost forever.

The lexicon of power

In Pollock's Avant-Garde Gambits, nothing less is at stake than "the deep structure of modernity." Abstraction, one often hears, has allowed painters to assert their humanity in a commercial age. Their formalism calls attention to the resources underlying artistic creation—psychological, material, and institutional. Pollock traces their ploy to Paul Gauguin and his trip to Tahiti and his later return to images of peasant Christianity in France.

In both moves, she argues, Gauguin sought to escape the growing pressures of urban unfeeling. He was rewarded with spirituality and an equally comforting "demonic sexuality." That meant, however, denying the reality of others: the wife he left behind and the thirteen-year-old Tahitian girl he married. In his art as in his life, women stand as mere projections of his need. Thanks to his travels, painting has become a fetish, even before abstraction. Gauguin took what he wanted, as complacently as a colonizer then—or a tourist today.

When Pollock first delivered her lecture, her audience of art historians felt "a certain amount of discomfort." It was, they imagined, "an indictment." In the printed text, she takes care to disavow any intention to set herself "righteously apart." Born in white South Africa, she admits her own complicity in "a lexicon of power and privilege."

I shall argue that her audience was right, because she is right about her lexicon. Like a tourist herself, she approaches and denies her audience—and, indeed, Gauguin—from a position of easy superiority. In fact, her unconscious use of Gauguin's strategies only adds to the interest of her essays. Together with their insights, even her simplifying rhetoric will turn out to prove the persistence of the modernist vision.

Lust for life

Pollock begins, ironically enough, more like an entertainment seeker than an art historian, with a scene from Lust for Life. In the movie Gauguin blusters that "I like my women fat, vicious and stupid with nothing spiritual." Then, dragging Vincent van Gogh along to a brothel, he accepts a woman's "inevitable submission." It sounds like a foretaste of Tahiti, and it is. But how much it leaves out!

Gauguin really made his boast in a letter. In that context it was not about tavern manners. It was a painter's revolt, a protest against long-settled images of sweet, passive women. It confronted any sentimental spirituality, whether Christian or Tahitian. Pollock has missed the tensions here—between a painter's sexism and realism, between his ideology and often sentimental execution. These conflicts could unveil a disturbing but productive complexity in Modernism, but they remain unexplored.

Like Gauguin's depictions of Tahitian culture and his copy after Manet's Olympia, Pollock also denies the reality of the brothel, of a woman's uneasy choices. The whore, she notes, "withdraws her attention from van Gogh." As no doubt befits a cinematic fiction, the poor woman sounds like a free agent, capable of dealing quite well with Gauguin. In the same way, Pollock elides the Tahitian girl's lack of freedom before the Frenchman's arrival. The painter was not importing patriarchal western values. Rather, he was exploiting the patriarchy he found. Once again, it may well be Pollock who plays pleasure seeker.

Pollock is caught within "Minelli's sophisticated movie." (It may be the first time that Vincent Minelli has ever been called sophisticated in quite that sense—intellectually subtle rather than fashion conscious.) She sees only a man's ideal sexuality. I see a creep whose boorishness consists precisely in refusing ideality to women. In her displacement of Gauguin's art into Hollywood, Pollock accepts the rhetoric that she hopes most to reveal. She will do so repeatedly for the rest of her lecture.

Eminent Victorians

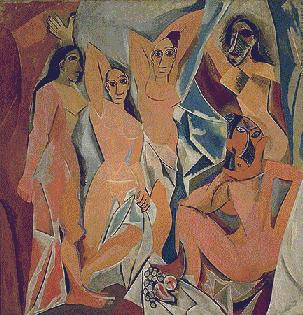

Pollock's actual argument starts by noting how modern artists have reflected their sexuality in their work, like the disturbing fixation on prostitution in German Expressionism. Her careful look reminds me of others who associate gender and desire with the act of seeing itself, such as Jacques Lacan and Laura Mulvey. She observes Gauguin's influence on other brothel images, such as Picasso's Les Demoiselles d'Avignon. In all this "uncritical celebration" of male desire, gender is repressed. I can only imagine what she would make of Picasso's nasty portraits.

She sees something, but this is far too easy. When men foreground their desire, they might actually enable criticism of gender. They might promote a climate in which all people, women included, could celebrate sexuality openly. Or they could merely be using all of themselves as subject matter for their art, which for Gauguin just happened to be male. Perhaps in modern art all these statements, Pollock's as well as mine, can simultaneously be valid. The lecture never pauses to ask.

Art is complicated enough to need interpretation. It will not do to confuse subject with meaning. Many periods have a familiar set of stories. Meaning lies at least partly in what an artist does with—or against—that inheritance. Pollock briefly mentions Artemisia Gentileschi, who recast such excuses for male leers as Susanna and the Elders or Venus and Cupid. This great woman artist turned representations of dirty old men against her seventeenth-century tormenters.

The problem, again, is a rhetoric of certainty. Pollock's style exploits what it sees and despises expressions of desire. When this woman from England's fading empire asks to leave sexuality out of polite company, she may be more Victorian than she thinks, enough to banish even Diane Arbus and her probing female gaze. Like her, too, British Modernism has been locked into a limiting realism, with its own gaze like a tourist's stare. It has worked outward from its subject matter rather than inward from its rhetoric. Along with her compatriots, Pollock enacts the ritual of the colonizer.

Cops and robbers

Generalizations about sex make a bad start for a feminist. Pollock may realize this, and so she goes on to make her case historically. However, her recourse to history creates another suspicious monolith, her view of Modernism.

In Olympia, she begins, Manet displaced Titian's nude to a modern brothel. His subject's glance out of the canvas projects a breathtaking self-awareness. The nude challenges both art history, academic rituals, and the male viewer, who is forced to enter the painting as one of its subjects—and a pathetic one at that. Gauguin, in contrast, retreated to passive women, and his later turn to Christianity was even more escapist. He distanced himself from an oppressive urban culture, but he could do so only by placing himself into a privileged position within a "primitive" society.

Gauguin, Pollock continues, set the content for all of Modernism's later indulgent escapes, from Picasso's Blue Period through abstraction. Both Gauguin and Picasso accepted Modernism as a game, a male institution with comfortable rules. Painters fully understood the rules of admission, which also included painterly concerns in Les Demoiselles that Pollock will never see. They already knew how to refer to tradition and when to defer to it, when to mask it in the primitive and when a "Primitivism Revisited" could unmask the West. All they had to add was the avant-garde mark—to differ from tradition.

Note that one has to take Gauguin as the emblem of a unitary Modernism. I desperately wanted to interrupt. Whose history defines this institution? I have long disliked Gauguin, much for the reasons she describes. His art does seem sexist, and he, like Amedeo Modigliani, does put on airs of exoticism, of direct access to ultimate truths. It is Manet and then Cézanne who appeal to me and, more significantly, who have been idolized by so many modern painters, from Matisse and Picasso through color-field abstraction. I shall suggest why modernists have made these choices in a moment.

First, however, consider Pollock's oppositions, of Manet to Gauguin or of Gentileschi to Titian. These contrasts too define an institution. They tell her audience whom it is safe to admire. Real history is much more complex. Manet, for example, was both challenging the presuppositions of art history and admiring the tradition greatly. The paradox of such an appropriation itself creates meaning, and it lies at the heart of Modernism.

The ironies of tradition cannot be captured in her formula of reference, deference, and difference. Artists beg to differ out of their love. They refer in order to create the difference. They defer where it allows the image, the referent, to live and breathe.

Pollock denies that she is playing the same game, that she ever hoped to defer to or differ from her audience. The reader knows better. Every page of her text breathes that vocabulary. Their creation of da good guys and, of course, da bad guys is straight out of male-centered) sports and movie genres. This is a shootout.

Spirituality and the urban paradise

It is not unfair to begin with Gauguin. There can be no escaping his rebellion against urban culture. Like Gauguin, too, artists always inject themselves in the subject matter of their paradise. However, it is wrong to see Modernism exclusively as patterned on his idealism, privilege, and backward-looking mysticism. If Modernism is escapist, it might be traced to earlier forms of escape, but Gauguin's evasions cannot be taken as proof for an interpretation a century later of an art yet unborn.

Pollock argues that tourism provides a "direct access" to "the form of modernity," "precisely analogous to a religion." At the very least, she confuses a potentially useful metaphor with a central myth, as facile as the coy, misspelled Tahitian beneath Gauguin's blunt, dark women. It also places her within structuralism, as if structure determination were not itself a myth of appropriation. (The point has been made by Gayatri Spivak, a critic whom Pollock too admires.) Again, the lecturer is the colonizer.

Ultimately, against its will, Modernism was forced to create its own myths, which is what abstraction is so often about. Its formalism is neither evasion nor deference. When it is most spiritual, as in Kandinsky's compositions, it is most objective. And when it becomes a literal emblem of the artist, as in Cubism or Minimalism, it is most tied up in the shards of the gritty, urban culture that Gauguin rejected. To turn expression into a brushstroke or a glass cube allows the viewer to fetish neither artist, gesture, nor the substance of urban life.

Modernism's placement of artist and viewer within its myth liberates both the spirit and the urban observer. It also puts both on the spot, much like the scandal of Alfred Jarry and Ubu Roi before it. That is why it sides with Manet and Cézanne against Gauguin. In Minelli's tavern scene, even the male modernist could well be walking out, phoning the police, or siding with van Gogh, whose fatal madness was hardly compatible with a penetrating eye. Or he could be siding with Gauguin and secretly ashamed of it.

I see room for a different model of tourism. As in the comic sculpture by Duane Hanson, a tourist is the rural gawking at the big city, not smart enough to avoid the theme park, the smart hustler, or the suspicious cop. Video artists such as Jon Routson and Christian Jankowski (or Janet Cardiff, although she might best be considered sound art or tour guide) make every moviegoer the subject of a sneak preview. Tourism may also be the transfer of idyllic satiation to a modern setting—the Hard Rock Cafe or a cruise ship.

Hanson, of course, is only a momentary diversion, not a great modern artist. Real tourism, however, may yet offer a useful metaphor for Modernism. It suggests a different dynamic of escape, in which artists rebels against and subjects themselves to modern commercial culture. Maybe that is a clue to the power of modern art. An ironic virtue of Pollock's attack is to evoke that power. She helps to explain the limitations of Modernism as well, limits that artists—both men and women—have begun to challenge and to reexplore.

This review appeared in a slightly different form, in the late lamented Cultural Studies Times (Fall 1995). It had the virtue of provoking its audience, but also the embarrassment of annoying its subject. I hope now to insist on conflict as the best kind of respect. We are both convinced of the need for feminist art histories, and we both think that demands getting around the craggy mountain called Modernism. I want only to help find new strategies as postmodern as our aims.