The Dying White Male

John Haberin New York City

Picasso's Mosqueteros and Marie-Thérèse Walter

If timing is everything, the epic Picasso retrospective had it all. Almost thirty years later, he again has his timing down, but I am not sure about his art.

"Picasso's Mosqueteros" selects from only his last decade. It shows an artist confronting death and still eager to paint. It also asserts something about his whole career. Once Picasso stood for the genesis of Cubism and modern art, followed by fifty years of slack. He also stood for the arrogant male artist looking down on his wives and mistresses. Now the dead white male has become the dying white male—and a suffering one at that.

Has the pendulum swung the other way? Jerry Saltz, for one, has a problem with that. He loved the show, but the critic also notes how little women have entered the Museum of Modern Art. Maybe anyone riding the pendulum should take heart: his readers shared his anger, and even MoMA has changed since 1970. Feminist criticism is alive and well, and it had better be.

As a postscript, a lot can happen in a moment. Even more can happen in fifteen years, the years since Cubism. Gagosian makes much of that moment in January 1927, when Picasso met Marie-Thérèse Walter on a Paris street. Could a man and a woman make art together? It ended up taking a while.

A bad boy's old age

That epic retrospective came in 1980, just shy of one hundred years after the artist's birth. It also came just as Modernism's unanimity was shattering into today's cacophony. It returned to Modernism's icon, a great white male, and he had never looked better. It was not, however, a typical modernist history. It did not show Cubism as a single, isolated great experiment. It did not show only egotism and conservatism before and since.

Each room came as a fresh start, as Pablo Picasso teased out what he had done and what to do next. I was pretty new to art then. I knew the hard-line account, as in John Berger's The Success and Failure of Picasso, in which the young Picasso was all sentiment and Picasso's art dies with Neoclassicism. I had spent free Mondays with the Modern's permanent collection. But I had seen nothing like this. It managed to be both exhausting and invigorating.

"Picasso's Mosqueteros" is not likely to exhaust anyone, although the lines outside might. Instead, it is invigorating, more so in fact than any of the paintings. The large show covers just the artist's final decade. Even staunch supporters have largely given up on him by then, and a 1984 show at the Guggenheim did not make many converts. Always prolific, Picasso churned things out, perhaps with an eye to the value of his estate. Yet for all the truly awful work of his on the market, this time his very glibness feels gutsy—and even a little too relevant to the present.

The curator, John Richardson, presents the final decade as not a fresh start but a self-conscious ending. He sees the artist, who died in 1973, taking on the roles of a younger man from his art and others. One last time, he plays the lecher. One last time, he poses as a musketeer out of Rembrandt, Diego Velázquez, or Edouard Manet—who was already playing against the Old Masters with his "Beggar-Philosophers." In the process, the old tricks of Cubist portraiture become an act of defiance, against the art-historical competition and against death. They also represent an old man's fragility.

He can seem jaunty, scarred, or confused. With those eyes simultaneously facing and in profile, he can seem all of them at once. As a jester out of Velázquez, he looks little more than a clown. As a seated musketeer, his sword on his lap sprouting a flower, he looks like a peevish child. In Les Demoiselles d'Avignon, his many wives and mistresses, and his echoes of "the primitive," critics have slammed his ever-confident male gaze. Here he turns the same gaze on himself.

For all that, Picasso stays confident enough to dress for the occasion and to play. He allows self-exposure, but never lyricism or terror. He paints mostly in bright colors and thick, rounded forms. He plays down the anguished gestures from Guernica. He never reduces himself to an empty mask, as in Three Musicians. Rather, his eyes are everywhere, taking it all in.

Dressing for his own funeral

They also take in his last wife, Jacqueline Roque. She, too, comes off as confident and exposed. She toys with a cat, while posing as an odalisque with naked crotch. In my favorite painting, Picasso brightens and effaces her with a smear of color. Modernism was never all that unanimous anyway. His manipulations alone would have seen to that.

Modernism had more than enough movements at war with one another. By contrast, Chelsea's paradigm of installation art gets stifling. MoMA's first Picasso retrospective already covered "Fifty Years of His Art," although it necessarily had to stop in 1946, at the height of his influence on a new American art. Richardson's biography of Picasso thus far covers three volumes and takes him only to 1936, the last year of a Picasso sculpture studio northwest of Paris. The 1980 retrospective made him the first and most persistent appropriation artist—not just of Cubist newsprint, but of his own life in art. His last decade tells much the same story.

This show will not settle the controversy. Cubism really did mean something special, and Picasso really does get glib to the point of empty. Some critics have found the exhibition fierce and jarring, as I do not. Even with careful selection, it repeats too often his virile role as a Greek seaman or satyr. Others find it stirring and insightful, but with maybe half a dozen great pictures. It says something that they cannot agree on which pictures.

Still, the show brings the aging artist alive. It brings him most alive as a painter, despite a separate display of Picasso drawings. If one thinks of Picasso and Matisse as line and color, here he works very much in color. Even in black, he insists on its texture as paint and on more than Picasso in black and white. At its brightest, it gets cakiest. In a wall of mostly pale blue, it thins almost like watercolor.

He comes alive, too, with his timing. He gets a "museum quality" gallery show, with lines, just as the economy has people wondering about the role of the market. He plays the bad boy, just when bad boys are everywhere. Martin Kippenberger at MoMA and Dana Schutz both rework Picasso self-portraits as emblems of an artist's exhaustion. Sure enough, he had done the same before them. All this helps explain the excitement this show created.

Yes, Richardson did his homework, and yes, too, a new generation is always ready for a new Picasso, especially after the old Picasso is no longer for sale. Through his late work, a wider audience for art may discover his tricks for the first time—after they no longer fooled anybody. Mostly, though, the applause says something about art now. No longer driven by ideology, it accepts and rebels against almost anything. It depends on big shows about bad boys, and Picasso is still the biggest and baddest. Almost thirty years after his retrospective, he anticipates the best and worst of the present.

Four percent

He also cannot settle yet another myth that he contributed to Modernism: while males rule and misrule. On Facebook, Jerry Saltz has made waves with a simple statistic: of the 383 works on the fourth and fifth floors of MoMA's permanent collection, only 19 are by women. The representation grows a bit if one counts the relative numbers of artists—from four to six percent. If no one can challenge Picasso, can anyone still challenge Modernism? The Modern has a founding mission to present the modern and to keep it up to date, It is getting harder and harder to do both.

Saltz confirms his passionate art journalism, and yet my first impulse was to stifle a yawn (or to check statistics on his own columns). And that impulse was wrong. True, after some forty years of feminist criticism, this counts as old news. The Guerilla Girls made statistics like this famous. The very idea of Modernism, the basic subject of those two floors at MoMA, now comes in scare quotes. The sheer pile-up of Facebook comments in agreement could make anyone, like the wise old advice about America's involvement in Vietnam, declare victory and run.

The Modern offers plenty of evidence of change all by itself. Marina Abramovic, Janet Cardiff, Chéri Sambahave, Dana Schutz, Cindy Sherman, and Rachel Whiteread all left a profound mark on "Take Two," the museum's very first display of art after 1965 since its 2004 expansion—a show co-curated by a woman. (MoMA had snapped up Sherman's Untitled Film Stills well before "The Pictures Generation" became history.) A display of Rhapsody by Jennifer Bartlett in the museum atrium meant to shake up postwar art history, and it did. Just this half year, MoMA has exhibited Pipilotti Rist, Mira Schendel, and Klara Lidén. P.S. 1 has been busy with Yael Bartana, Lutz Bacher, and an epic display of women's art, WACK!—not to mention signs of diversity in NeoHooDoo and Jonathan Horowitz, a gay artist.

A feminist should be wary of statistics anyway. Feminism has always had to juggle several critiques, without falling into contradictions. The canon has failed to recognize women, and women have not often had the chance to become artists, much less great ones. The very notion of broadening the canon can enshrine it—and so enshrine an ideal of fine art that excludes craft and design. Linda Nochlin meant all these when she asked Why Are There No Great Women Artists? To its credit, MoMA was pioneering in making design a part of Modernism's history, although a better museum design in 20004 would not already find itself so short of space.

Saltz refers specifically to art before 1970. One can argue that the older collection can and should expand only slowly, given MoMA's role in creating a modernist canon. One can argue that it will expand even more slowly now, given outlandish auction prices and recession economics. And yet the data persist. Saltz had no trouble listing interesting artists in the collection who do not make it onto the walls—including Joan Mitchell, Louise Nevelson and Nevelson's black, and Dorothea Rockburne. It broke my heart that, for several years after the museum's vast expansion, it no longer had room for Janet Sobel.

What can one do? For starters, one can still keep all of feminism's balls in the air. (Right off, this proves that feminism has balls.) Feminism can also change how one appreciates male artists. Saltz rightly asks, too, that prominent bloggers (among which, I confess, I did not rate) get the numbers out. As someone who honestly hoped to make gender a priority of this Web site from its beginning in 1994, let me do so, too.

Picasso's mad love

"I am Picasso," the artist announced that January, with the accustomed arrogance of the great man and lady's man, not least in his own eyes. It hardly matters that she was less than half his age and had no clue who he was. It only adds to the mystique of the moment—and they remained lovers until at least 1936, when their child, Maya, was born and Picasso, still married to someone else entirely, fell in love with Dora Maar. For these years, profound love was tied up with profound betrayal. Marie-Thérèse Walter hung herself in 1977, four years after he died. Yet many of the show's hundred works look happy and calm, an inventory of love and of Modernism itself.

This is no longer Picasso in 1912, still the anarchist in art and, more often than not, in politics. In Montparnasse, he was part of a community very much aware of Synthetic Cubism and those paper guitars up at MoMA. And the change since then has to do not just with the artist, but with modern art. World War I struck at its optimism, especially with German Expressionism, and recovery from war had helped it settle down into something of an institution, the School of Paris. The avant-garde had broken up as well, into movement after movement—and Picasso made use of them all. So it appears, did the face of Marie-Thérèse.

Or isn't it pretty to think so? The curators do, and they make a strong case. John Richardson joins with Diana Widmaier Picasso, Maya's daughter and an art historian now cataloguing Picasso's sculpture. In drawings or bare curves on nearly bare white canvas, Walters's earthy features go easily with the Neoclassicism of the late 1920s or with striking displays of skilled realism. They guide heavy black casts, plaster fragments like a classical frieze, and small, thin wood sculpture akin to Alberto Giacometti. They lurk in the Surrealism of a deep kiss turned into predatory biting, a woman's legs as crab pincers, or the female on female rape of Le Sauvetage—as a third woman rises from the earth as a victim, a witness, or a plea.

Or isn't it pretty to think so? The curators do, and they make a strong case. John Richardson joins with Diana Widmaier Picasso, Maya's daughter and an art historian now cataloguing Picasso's sculpture. In drawings or bare curves on nearly bare white canvas, Walters's earthy features go easily with the Neoclassicism of the late 1920s or with striking displays of skilled realism. They guide heavy black casts, plaster fragments like a classical frieze, and small, thin wood sculpture akin to Alberto Giacometti. They lurk in the Surrealism of a deep kiss turned into predatory biting, a woman's legs as crab pincers, or the female on female rape of Le Sauvetage—as a third woman rises from the earth as a victim, a witness, or a plea.

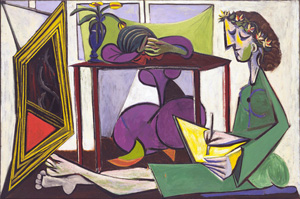

One thinks of Picasso's women more as studies in torment than of love, but he treats her again and again as a creative partner. Desire here is almost always wrapped up in art. A brunette to Marie-Thérèse's actual blond, she wears the garland and rich cloth of the artist's worldly muse while sketching herself in a mirror, implying two further images that one cannot see. A woman sleeping between her, in the warm red of an evening shadow, could be her actual sister or a further redoubling. Quite a few paintings look like studies for sculpture, turning her into a figure out of the imagination. The imagination, in turn, emphasizes the interplay between the visual and the tactile, as another token of feeling.

Mostly, though, starting in 1931, painting adopts a version of Cubism with little fragmentation, broad fields of color, occasional Pointillist decoration, and plenty of Marie-Thérèse. As late as 1939 she looks slyly in two directions at once, while leaning on her elbow allows her to gesture in two directions as well. The show bears the subtitle "Amour Fou," but one sees little in the way of madness—and anyway André Breton did not complete his Mad Love until 1937. Breton called desire "the only motive of the world," but Picasso treats her more often with restraint. She is almost always seated, whether reading by candlelight, drawing, or sleeping. Her calm contrasts with the sweep of her thigh and scarf or with the half moon of her face.

All this ambiguity between dignity and madness marks something of an interlude. It distinguishes the decade between Surrealism and Guernica or between Cubism and a deplorably glib self-portrayal in 1938 as philosopher and satyr. It lacks the shocks of Picasso's 1980 retrospective, a story of continual reinvention. It explains why Gagosian's take two years ago, with late images of failed desire, came as a very good show about very mediocre art. This comes rather as solid but modest show about very good art, with quite a few museum loans to match. It brings Picasso's madness fully into the mainstream.

Work from Picasso's last decade ran at Gagosian through June 6, 2009, "Picasso and Marie-Thérèse Walter: Amour Fou" through July 15, 2011, and Dana Schutz at Zach Feuer through April 25, 2009. Jerry Saltz's hotly debated Facebook threads centered around the last weekend in May. A later review catches up with Dana Schutz in 2019.