A Renaissance Finds Its Art

John Haberin New York City

The Harlem Renaissance and Transatlantic Modernism

"Lift every voice and sing, / Till earth and heaven ring." For two splendid decades after World War I, with Jim Crow still a vivid memory, there was a place for African Americans to believe in "a song of hope."

What was the Harlem Renaissance, and where would a Renaissance be without painting? It must sound obvious, but even now people argue over the period's legacy and its substance. With "The Harlem Renaissance and Transatlantic Modernism," not every voice is singing. Politics is largely absent, and jazz itself is all but silent. Modernism seems curiously far away. Yet the Met makes an overdue case for its art.

Prouder and darker

You may think of the Harlem Renaissance as above all a literary movement, with Zora Neale Hurston and Jean Toomer in fiction, Countee Cullen in poetry, and Langston Hughes towering over both forms of expression. James Weldon Johnson, at the head of the NAACP, wrote of a "flowering of Negro literature." You may think of it as a flourishing of theater, dance, and music, with such jazz greats as Duke Ellington, Fats Waller, Fletcher Henderson, and Bessie Smith—and Johnson himself composed hymns, including what some have called the black national anthem, "Lift Every Voice and Sing." Or you may think of it as a broader intellectual achievement. It stands as a rebirth for black culture itself. Hubert Harrison spoke of the "New Negro" as early as 1917, and Alain Locke took that for the title of an anthology of fiction, poetry, and essays in 1925.

It was surely a rebirth for Harlem, neither the first nor the last. Harlem had served Dutch farmers and then city dwellers, as the first elevated trains headed uptown and a wave of European immigrants, many of them Jewish, sought affordable housing. Things changed once again in the twentieth century, as the Afro-Caribbean diaspora reached New York along with the Great Migration from the rural, racially oppressive South. Jazz came north from New Orleans with it, Louis Armstrong included, to found the swing era. The Apollo Theater had opened in 1914—improbably enough, for burlesque shows aimed at whites. It became the fabled venue for blacks only twenty years later, thanks to a new Jewish owner.

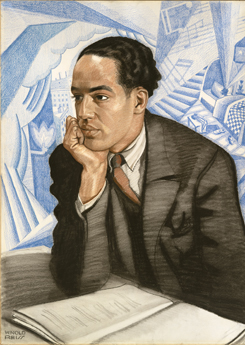

The Met boasts right off of literary and cultural ferment. It opens with portraits of Locke and Hughes by Winold Reiss, Hurston by Aaron Douglas, and Johnson by Laura Wheeler Waring. Reiss, a German who found the rest of New York boring, brings his wiry black outlines broken only by the meticulous realism of his faces, suiting Locke's hauteur and intellect. The pale patterned backdrop to Hughes hints at a ferment within painting itself, in early modern art. Douglas and Waring stick more closely to realism to flatter their subjects and their dignity. Then come portraits and street scenes, where ordinary men and women get to dress up, too.

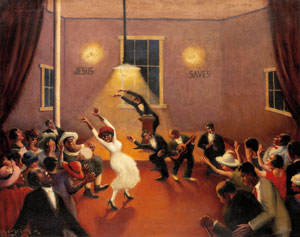

The curator, Denise Murrell, is introducing not just a culture. She is assembling the artists who will render it. All three from that first room will turn up often, as will Archibald Motley and William H. Johnson. Motley brings the intensity of artificial light to equally unsettling narratives. Johnson has the brighter colors, flatter renderings, and impasto of folk art. Together, they set out the possibilities that other artists will explore, in a show of one hundred sixty works.

This is a proud culture, of parades by day and nights on the town. Both appear in photos by James Van Der Zee, as counterpoint and confirmation. (Van Der Zee ran often in the lower level of the Studio Museum in Harlem, and I trust he will be back with that museum's expansion and reopening.) People for him look calm and collected even in motion. They set out in cars and take breaks for tea or for luncheon in a women's salon. They are happy to pose for an authoritative, sympathetic eye.

Could it also be a darker, more spontaneous culture? While propriety rules on the surface, Motley sees more. He shows men as Plotters, but the plot is unraveling fast. Even a picnic in his hands has a tight space and signs of confrontation. The unnatural colors of black skin in harsh light add to the uneasy mix of celebration, anger, and despair. A pool hall for Jacob Lawrence, diagonals running every which way, looks under control by comparison.

Harlem as cultural capital

So was the Harlem Renaissance an art movement, as tumultuous and diverse as its time? Not everyone has thought so. Its Wikipedia article lacks a section for art and mentions, without attribution or comment, a single painting. More notoriously, a 1969 exhibition at the Met had no painting at all. "Harlem on My Mind" has entered history as a model of what not to do, but it was nothing if not well intentioned.  It set out, in the words of its subtitle, to capture the "cultural capital of black America."

It set out, in the words of its subtitle, to capture the "cultural capital of black America."

Not that I can know, as a white who never attended. For me as a child, the Met meant the pyramids, just as the American Museum of Natural History meant the blue whale. And whites have always made a hash of good intentions, maybe especially then, before the resurgent right. Mayor Lindsay walked the streets while other cities were in flames, to reassure the community. It took Colson Whitehead in his Harlem novels to remind me that New York succumbed to riots and looting, too, always at the expense of blacks. Still, the exhibition had Harlem on its mind at a time when "cultured" America would just as soon look away.

It sought what its curator, Allon Schoener, called Harlem's great "achievements and contribution into American life and to the city." It covered an entire century in progress, the civil rights era included, with a visual splendor and scholarly care. It drew on Van Der Zee, Gordon Parks, and other black photographers for its murals, along with articles from the mainstream and alternative press. It planned the show in cooperation with a community advisory committee that met regularly at the public library's Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture. In case you are wondering, that means it met in the shadow of a mural on black history by Douglas himself. What it did not have was painting, his included.

It was a recipe for disaster. Even before its opening, the protests began, mobilized by artists. To them, the exhibition treated blacks not as creative individuals, but as anthropological specimens. They wanted their voices heard and their art to be seen. Remember that such giants as Lawrence and Romare Bearden in Harlem were very much alive—but not at the Met. The show took place before much of today's audience for art was born, and it might look a bit better today, when photography needs no excuse, but the damage was done.

To its credit, the Met did exhibit contemporary African American art, for the bicentennial in 1976, and other institutions are still catching up. The present show is less an apology than a continuation. It is all about and only about the Harlem Renaissance. Could that end up highlighting why American art between world wars was neglected in the first place? From the opening portraits, the work can seem conservative, like its sitters' ever so proper clothing. When Hale Woodruff paints card players, with a nod to Cubism, or a tree at twilight with the terrifying colors of Fauvism, he cannot help standing out.

In avoiding an ethnological exhibition, the Met also avoids memorabilia of theater, dance, and music. So often enough does the work. Ellington himself, the Cotton Club (which departed for midtown in 1936), or the Apollo theater never once appears in paint. Nor do clues that Modernism might favor, such as books and recordings within painting, with painted text on their jackets. The show recreates a great era all the same—and helps to make it great. This will be the essential history of the Harlem Renaissance starting now, until of course the next one.

To Paris and around the block

After the extended introduction, through literary leading lights and narrative, there can be no question of the abundance ahead as things settle into portraiture. If the Harlem Renaissance was about anything to these artists, it is about who they and the community are. A girl in red by Charles Alston, her tartness set off by brushy whites careering across sky blue, takes real chances. Others aim instead for composure. Artists wear ties for their self-portraits and, by implication, for their craft.  Horace Pippin signals his self-assurance with tense lips and raised eyebrows, while his wife in a portrait wears her Sunday best.

Horace Pippin signals his self-assurance with tense lips and raised eyebrows, while his wife in a portrait wears her Sunday best.

Portraiture never does go away, and a late room for family portraits does still more to show respect. First, though, comes a delightful surprise—a full room for Douglas, where that mural from the Schomburg Center lets in the light. Shadowy figures set against glowing bands of pale color act out fragments of the Bible and African American history. They run from the creation to the last judgment and from a slave auction to emancipation, and it is hard to know where Genesis ends and history begins. In each case, surely some revelation is at hand, and it has to be the Harlem Renaissance. It has to, so long as it can capture the light.

Sculpture appears more and more as well, scattered throughout, starting with a larger than life face in wood by Ronald Moody. Freestanding sculpture runs to figurines out of African art or Harlem, and who would dare say which? And that raises an overdue question: what exactly are the roots of the Harlem Renaissance and what will serve as a model for today? Will it be modern art, street art, folk art, African masks, or something altogether new? Just how conservative was this art all along?

And now, more than halfway through, the show turns to its title. The Harlem Renaissance as transatlantic Modernism may sound empty, although Locke himself asked to see the two side by side. It could be a self-conscious rejoinder to "Harlem on My Mind"—a boast that black artists can stand up against anyone. Regardless, three full rooms take Motley to Paris and European art to the United States. Pablo Picasso could not care less about New York, where Cubism failed to sell, and Edvard Munch has only a circus performer to show for thoughts of a city he had never seen. Henri Matisse, though, did make it here, and his choices stand out.

Motley, in turn, loved his time abroad. He felt at home in dance clubs much like the ones he knew, with the same dark colors and clashing bodies, including blacks. Like the creoles he remembered from New Orleans, they even spoke a form of French. Once again, though, the section has to leave you asking: however glorious, how progressive was this art? Motley comes closer to a young Picasso at a club in Montmartre than to transatlantic Modernism, while Consuelo Kanaga, not in the show, emerged from the avant-garde in America.

The show's greatest pleasure is that it need not answer the charge. It can only keep looking for more. Sure, here Harlem itself lacks specifics, if not fashion sense. Yet a final room, easy enough to miss on the way out, does take to the street, for the eighteen feet of The Block, from 1971. Bearden, then in his sixties, had been around the block, "Harlem on My Mind" was two years gone, and the Harlem Renaissance was history. The mural's triumph may drive home the movement's limits—or its importance for the future.

"The Harlem Renaissance and Transatlantic Modernism" ran at The Metropolitan Museum of Art through July 28, 2024.