Still Painting

John Haberin New York City

James Hyde and Melissa Brown

Anna Ostoya and Sarah Crowner

I confess. No matter how often I encounter paintings by James Hyde, I still think of him as a sculptor.

Wrong or not, he could almost have the same confession to make with a show called "Public Sculpture." It may be his wildest approach to painting yet. But whatever painting is today, there is sure a lot of it. Rather than try to sort it all out, consider Hyde along with an illusionist without illusions, Melissa Brown.  Consider, too, two others who may or may not be working in mixed media, Anna Ostoya and Sarah Crowner. Their bold, even wild effects take simple steps and discipline.

Consider, too, two others who may or may not be working in mixed media, Anna Ostoya and Sarah Crowner. Their bold, even wild effects take simple steps and discipline.

Not so public sculpture

I know, it makes no sense to think of James Hyde as anything but a painter. Yet he does have a way of pushing the limits of geometric abstraction. Another artist might do it by abandoning geometry and painting, like Frank Stella. Still others do it by multiplying geometric forms in greater and greater detail, like the broken symmetries of Gary Petersen or Op Art from Bridget Riley to Rob de Oude. Hyde, though, has little interest in systems or illusion. He just wants to paint, and if that takes painting off the wall, he can always bring it back.

Hyde's break with the wall can be modest, like a strip of linen and a block of wood. It can go further, to mimic furniture or architecture, like less than easeful easy chairs, shelves, "cosmic pillows," or an entire canopy—all, of course, painted. It can approach the irregular spills of Judy Pfaff. Still, Hyde keeps things simple and solid until, that is, they find their way back into the picture plane. And that is when things really get messy. Even when he has indulged in gestural abstraction, the layered brushstrokes might almost belong to separate pictures.

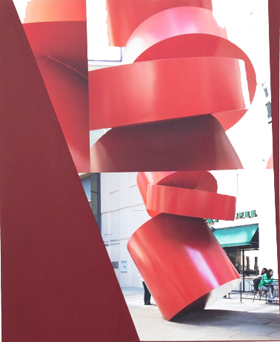

Does that make him a sculptor after all? Not really, but he looks afresh at mixed media in "Public Sculpture." As for sculpture, he leaves that to others. He begins with photos of actual outdoor installations. And then he paints or prints over them, riffing on their shapes and colors. That makes perfect sense for an artist whose vocabulary runs to open and filled circles.

You will recognize the bright reds and tumbling geometries so common since Alexander Calder, Mark di Suvero, and Joel Shapiro. You will recognize, too, their ambition to fill and to create public spaces, but you will not recognize much else. Hyde dismantles things by closing in on them, with the buildings behind the sculpture as prominent as the art. Their façcades crowd in on the picture plane as well—to the point that the view out the gallery comes as a blessed relief. Titles are no help, giving at most the city and not the work. Public spaces become private affairs.

Hyde has looked before at photographs and the great outdoors, overpainting black-and-white landscapes with much the same painted geometry. There, too, the subject, often a rock face, has a way of closing in. He may have turned to photography to respond to a "culture of images," images of art included. How better to respond than to start there and to keep painting? As he wrote a few years back in Brooklyn Rail, "I confess I'm unable to form a solid definition of space." Count on Hyde for the double meaning of solid.

He was speaking not so much of his perplexity as an artist, although perplexity has been a running theme of his art. He was describing more the proper concerns for him of painting and sculpture alike. It allowed him to express his skepticism at the very idea of public spaces—or of space as the essence of art. Push "pure painting" hard enough, Stella's work might teach, and it becomes impure sculpture. In Chelsea now, Anne Truitt painted her final monochromes so thickly that her paper looks like sheet metal with torn edges, while Sam Gilliam at age eighty-six takes up paintings with wide beveled edges and sculpture itself. Push pure sculpture and photography far enough, too, I guess, and you might get delightfully impure painting.

A car to herself

I had a subway car to myself heading home from the galleries, right in evening rush hour. Any other year, I might have been scared stiff and moved to another car, but not this one. Thanks to the pandemic, it was downright comforting. But then, to judge by a painting, Melissa Brown had a car to herself on the way to the Lower East Side, and she loved every minute of it. And so she should, for she also had a terrific view crossing the Manhattan Bridge. If she or I was still nervous, that, too, makes sense for a show of "NYNY2020."

This is her New York in 2020, just as it was her commute from Brooklyn. If you never quite catch a glimpse of her, it is also her perspective. You see only her hand held in front of her, just as she could, balancing two small black spheres touched with white, like dark planets encircled by clouds. New York for her is an entire world or two, and she can hold it in her perfectly polished fingers. If she cannot help fiddling with it, twice over, her boast comes tied up in her reticence and her nerves. Her phone never once shows a selfie.

Brown cannot help fiddling with things, like J. J. Manford at the same gallery, to improve them but also to make them more unsettling. The Brooklyn Bridge out the train's windows has never felt so close and unobstructed as in another version of her ride, this time fondling her phone, and the on-screen image could only be its majestic cables. It could, that is, had they not become so tangled, like barbed wire. She finds much the same weave in the tracery of the glass behind the Temple of Dendur at the Met. The temple itself looks a bit ratty, but then she sees not Central Park through the glass, but more pyramids than Egypt ever knew. It is her Problematic Sanctuary.

She can escape by car, unlike most New Yorkers, but do not expect to see her in either rear-view mirror. (Yes, she does have her fine hand on the wheel.) One has instead the challenge of how the views add up. Mirrors here are always a challenge, not least when she uses them to perfect herself. The oval of a makeup mirror shows a total mess. Reflections off the glass building in another view from the bridge are more dizzying still.

The vanity rests in front of a window, leaving Brown the choice of whether to look within or without. She opts for neither, just the light show taking place on the window's shutter. To one side of the mirror, the slats have their single tone, while the spaces between have their streaks of color. To the other side, continuity goes, well, out the window. Brown takes advantage of an eclectic mix of Flash, oil, acrylic, and silkscreens on aluminum-coated panels. The outcome is both translucent and reflective, and the mirror itself is a total mess.

Brown has long had a fondness for turning visual displays into mind games. I caught her first in a group show, "CHOPLOGIC" in 2005, with images of folded money opening onto landscapes. Four years later, at a Lower East Side pioneer, her patterns multiplied even as their geometry settled down. (I compared them to a Web browser designed by Buckminster Fuller.) It has been a long time since—enough time for her perspective to shift both to and beyond herself. For a New Yorker like me, pictures of the city are as foolproof as dog pictures on Instagram, but I had almost glimpsed myself as well.

Drawing divisions

Paintings by Anna Ostoya really move. You expect no less in a show called "Motions," in the plural. Women dominate, from an artist who has played before on Artemisia Gentileschi and a woman's agency—the women nearly the height of a tall canvas, with a shared grace in motion. Some have their hands high above their heads like dancers, while profiles could be runners with that sense of release that comes from a long run. Compositions have their grace as well, with long vertical arcs and a horizontal rhythm of color. Ostoya is are not just going through the motions.

For all that, her figures threaten to get in each other's way or to isolate themselves for good. Runners have their separate profiles, high kicks, and jagged elbows, all of them dangerously close. Their flesh tones may turn to blue, against uncertain fields of black of white. Dancers have already tumbled onto one another, in neon colors. A denser canvas multiplies the action, in brighter colors and with collage. Its bits and pieces of canvas and other flat materials redouble the artist's drawing and the motion.

For all that, her figures threaten to get in each other's way or to isolate themselves for good. Runners have their separate profiles, high kicks, and jagged elbows, all of them dangerously close. Their flesh tones may turn to blue, against uncertain fields of black of white. Dancers have already tumbled onto one another, in neon colors. A denser canvas multiplies the action, in brighter colors and with collage. Its bits and pieces of canvas and other flat materials redouble the artist's drawing and the motion.

Ostoya is well aware of the tension. Titles include Leap, Float, and Forward, but also Slap. Dark fields lit by sparks belong to prints of marchers on behalf of Black Lives Matter, and who knows how much the nation will change? A handout, in the first person, confesses to her own fears for her progress as the show's deadline approached. Maybe she still wonders that she has made it to Tribeca. A side room has a mobile of sculpted or found objects by Virginia Overton, who enjoys the liberation and the clutter, too.

Accumulation and motion get along well together in much of modern art—from Cubist collage to Op Art and assemblage. Ostoya's flesh tones and rhythms could easily belong to newspapers in the first, more acid colors to the second. Just as important is assemblage as drawing. While collage appears only rarely, you could well find yourself up close to other works, to verify that curved, hard-edged outlines are not more of the same. The show could amount to two bodies of work or maybe three, divided by media or by colors and compositions, but they are working toward a single collective motion.

Sarah Crowner, too, relies on big curves and contrasting colors. She also has the same sense of collage as drawing—and as working with and against drawing. Her shapes might be pressed leaves or odder life forms, but determinedly abstract. Paintings have just two colors, in off-kilter combinations of ROYGBIV, with the same flatness and gentle shading for what might otherwise be foreground and background. They do not quite hide, though, further divisions across and within colors. Crowner, who has experience with three dimensions in ceramics, has cut canvas and sewn it back together.

The bold simplicity recalls a time of color fields and geometry by the like of Frank Stella and Paul Feeley. The neatly nestled cuts might pass for shaped canvas from back then, too—or, in wider and more ambitious work, multiple panels. They add to the dilemma of what counts as academic art today, with all the pressures to get a right and proper MFA—and, for a critic, what in the world to single out from the wealth of painting and abstract art. They are bold all the same, while tempering their simplicity with the cuts. You might find yourself up close once again, but now to determine whether the cuts are just incisions that come naturally with an artist's pencil. Nothing here is in motion, but it, too, depends on more than one kind of division.

James Hyde ran at Freight + Volume through January 10, 2021, Sarah Crowner at Casey Kaplan through January 16. Anne Truitt ran at Matthew Marks, Sam Gilliam at Pace, and Anna Ostoya at Bortolami, all three through December 19, 2020, and Melissa Brown at Derek Eller through December 23.