Political Asylum

John Haberin New York City

Kazimir Malevich and Suprematism

No wonder the inmates took over the asylum. No one else would have them.

It would sound familiar even without the movies. It could, in fact, serve to define the avant-garde. The outsiders take over art. The Salon des Refusés, the charming egotist from Spain, scraps of paper in place of oils, the "primitive"—they sweep into Paris, and the rest is history.

Or rather, the rest is art history, and the world goes on. It goes on, through world war and a brutal, decaying peace. It goes on, uncomprehending and undisturbed, except for an occasional public outcry from the high-minded. When Young British Artists and arts funding come under fire in America, it makes all that ancient history seem like today.

What happens, however, when the asylum takes over again—not just from the inmates, but from an entire country? For Kazimir Malevich, it brought a brief dream of liberation and a lasting nightmare. It also left perhaps the most visionary abstract art ever. At the Guggenheim, his Suprematism looks both glorious and a little forlorn, as if in wonderment at the possibility of an avant-garde then or today.

Cubism for boomers

Suprematism turns the whole idea of Modernism inside-out. Cubism, the Parisian sophisticate, arrives full blown, from without. Conversely, in place of African masks and reclining gypsies, Kazimir Malevich elevates Russia's own folk traditions. More strangely still, the outsiders soon become the official state art.

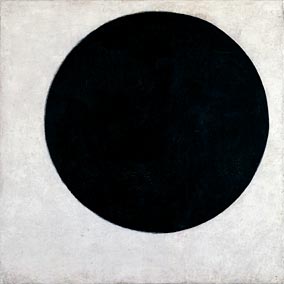

It makes for some heady stuff. Think Pablo Picasso offers much of a challenge? Sure, he intimidates museum visitors, even as they line up down the block to see him. Sure, confronted by his women, one hardly knows where to stand or how to look. Faced with Malevich's off-center squares, however, one may not even know which end is up. Curators still puzzle over how best to hang them. The paintings seem to belong not just in another room from Cubism, but in another time.

Indeed, in the 1960s and 1970s, with geometry everywhere, Soviet art came as an inspiration to painters like Mernet Larsen. Long before Robert Mangold dedicated himself to white, before Ad Reinhardt paints his black paintings or Josef Albers his Homage to the Square, Malevich paints white upon white. Tilted shapes descend on museum walls like a shaft of light, as ecstatically as florescent bulbs from Dan Flavin. They remove a distinction between painted image and object, as neatly as Ellsworth Kelly's crafted shapes. The unsettle the contrast between frame as boundary and frame as one more element of drawing, as fixedly as Frank Stella.

Or so it seemed. Like its architecture, the Guggenheim does look back to a purer world. With under a hundred works, it looks back to a time when art mattered most. Looking back across decades at Suprematism, art mattered more than blockbusters—and perhaps more than politics, context, conflict, and history as well.

Like the 1970s, the Guggenheim brings forth an idea. It detaches Suprematism from the entirety of a career. It detaches Malevich himself from a movement and its genesis. It could be atoning for missing exhibitions in pursuit of its museum empire. It could be making up for shows of fashion, motorcycles, and Matthew Barney.

Yet it does something new as well. In its look at a mere fifteen years, little more than a moment in at history, it restores Malevich to the strangeness of his time and place. For Malevich, the future begins with Russia's past.

Cubism for Russian mystics

Malevich begins with designs after Orthodox icons. By 1912 he has adopted a sort of Futurism, but not its all-over patterns or its faith in the machine age. He leaves its pale, overlapping planes to the rear and the urban crisis to Europe. In the foreground, peasants stand out in bright colors. They may come chopped into pieces, but the planes match the chests and thighs that drove an agricultural economy. Instead of dissolving laborers in motion, Futurist shaded edges make them all the more massive.

The next year Malevich takes another giant step backward—to the source, in Cubism's broken images and hand lettering. He designs for the stage, with a torn curtain. Yet again he takes the measure of a nation, as rooted in the past but only now coming into existence. Even the theater group's name, Algol, suggests a Russian collective almost as much as French logic. He is not trying to disassemble a medium or a point of view. As with the curtain, he is looking through the medium and toward the truth.

"The artist," he boasts, "has liberated himself from all ideas, images, notions, all objects arising from them and the entire structure of didactic life." Cubism toys with them all—ideas, images, objects, and old lessons. Malevich casts them aside. He does not mean, though, to dispense with objects, only with objects arising from ideas rather than from themselves. When at last he gets past quoting Cubism to understanding it, he pares it down to essentials that Picasso never imagined. No one has made a single circle or its departure from dead center so important.

Suprematism begins starkly after all this watching and waiting, much like World War I at the same time. Before long, however, the rectangles get busier and smaller, approaching the fallen fields of Zarina Hashmi and Minimalism. Malevich still hovers above each shape, as if looking down on an uncharted terrain. However, it definitely becomes a friendlier terrain, with the artist firmly in control. Perhaps the Revolution itself brought more confidence, and the new state gave Suprematism a big show in 1918, even before the experiments of early Soviet photography.

Still, Malevich never gives up on the themes of his early work, including its nativism. It all comes back to that twin focus on surface mass and image. One sees it in the titles—Football Player, Masses, Spatial Element, Mystic Suprematism. He sees no conflict between vision and matter, mysticism and form, or even past and future, because both take part in a specifically Russian form of modernity.

Unfortunately, Russia and Revolution soon had something else in mind. The nationalism he so prized took on a terrible momentum of their own. Malevich tries to keep up. Back come the human beings, if not quite at the level of Soviet Realism. Still, Suprematism's moment had already passed. He faced arrest in 1930 and died in 1935, leaving a fierce self-portrait with no hint of optimism or abstraction.

Priggery and Pragmatism

The Guggenheim skips the icons and the self-portrait. It cannot present the before and after. Instead, it gives Suprematism a history of its own, with its own version of inventing abstraction. Just a few years ago, the Museum of Modern Art surveyed the career of Alexander Rodchenko, he, too, a favorite and then a victim of Bolshevism. It uncovered a long trail of idealism and repression. Here, one sees the ideas and conflicts up close, seemingly day by day.

Drawing on regional collections in Russia, it runs to the return of the Suprematist human figure in 1928. It shows Malevich grappling with complexity as well as simplicity. How quickly the rectangles shrink and multiply. He layers it on, making each square a miniature canvas of its own. He adopts more explicit representations of space, with larger swaths of color that fade into white. In the 1920s, he even tries his hand at the redesign of society, like more than a few other Soviet artists, from architectural models to teacups that would do the Bauhaus proud.

In a sense, he really does grow closer than ever before or after to European Modernism. His mysticism, like the blank faces of his late human figures, has something of the shame at the flesh in Max Beckmann, Beckmann in New York, a Beckmann self-portrait, or German Expressionism. The Germans had the same idea in their movement's title, Die Brucke, the bridge to an unrealized future. Like so much of Picasso, too, Malevich shies away from the edge of the canvas. The frame serves above all as an arena for action.

In its Modernism and its Russian roots, Suprematism looks very unlike the compositional logic of the 1970s after all. Unlike Minimalism, too, Malevich turns to paint as a medium rather than a message—and often clumsily at that. He lacks the instinct for beauty in Rodchenko. He stands too far above things, with his blank faces, the windowless models, and the squares floating as if seen from an airplane. Besides, he may lack the skill. The black shapes are developing pretty serious cracks.

Paradoxically, however, even the clumsiness may bring Malevich closer to America and to art now. The cracks recall the dark landscapes of late American Romanticism, not to mention a few dirty installations today. All those overlapping rectangles make me think of cantilevered designs by Frank Lloyd Wright. So do the low-ceilinged architectural models. The masses and mysticism make me think of America's uneasy mixture of priggery and pragmatism.

It may all come back to the asylum after all. Perhaps only American art has a comparable story. America, too, reflects the collision of a Modernism imported from without and an idealism rooted deeply within. With America, too, the former avant-garde has entered art institutions and the economy, mostly at the expense of living artists. But what hope does that leave for a political art, then or now? After Postmodernism, can I even tell the difference between a rhetorical and an urgent question?

A kind of tribute?

Certainly the alternatives sound bleak. To give birth to reality, Malevich wanted to escape it, and escaping reality has a nasty sound. In a leisure economy, it means turning one's mind off—and perhaps one's heart as well. Besides, art has to be rooted in this world, because you are. These days the boundaries between fact and value, art and life, and all those other dogmas dissolve from under one. So, ultimately, does the line between the political sphere and ordinary feelings.

Conversely, art that lasts rarely continues to communicate its original political point well. Jacques-Louis David in his Death of Socrates, like political irony now, succeeds by intensifying moral conflicts almost beyond recognition. Some other earnest work had best go without mention. At other times, art that feels emotionally and politically relevant, like much of the Renaissance, overtly supports imperial regimes. Still other politically pertinent art, like that of Edouard Manet, does not obviously address politics at all. In the end, all get caught up in none too friendly art institutions.

It may sound hopeless. Formalism, including Suprematism, gambled that it could evoke the same awareness, self-awareness, and critical faculties that are aroused by political oppression. I make the same gamble when I write. Modernism hoped to open onto a wider world. It hoped to inspire a similar critical faculty in others. At least it refused to run away from anything—or did it? Sculpture in New York is still asking.

Malevich is trapped amid all those alternatives. He never gives up his fascination with a uniquely Russian spirit, which looks an awful lot like old-fashioned nationalism. He gets caught up in revolution. He enters the heart of a liberation movement, a belief in object, art, and society freed of false ideas. He sees all this in practical terms, of architecture and craft for a new culture.

At the same time, he refuses to let art stand for anything other than art. And throughout, he remains haunted by a spirituality that amounts almost to revulsion at reality. To a postmodern eye, all this has to feel urgent and quaint, just as the floating squares felt thirty years ago. One looks harder and harder to discover who runs the asylum. More than ever, America holds a mythic image of itself very much like one that brought terror to Russia and, through Russia, to the world. As so often before, it believes itself above history, capable of reinventing itself at any moment—by force of ideas, by force of will, or simply by force.

So call Malevich apolitical, anti-political, and fiercely political all at once. In just this way, he shows more passion than many an American political artist. in progressive and regressive, too. Still, Suprematism emerges from the Guggenheim surprisingly coherent, and art still presents and examines the possibilities for politics. Otherwise, governments and markets—from Stalin to the American right—would not have tried so hard to eliminate it. Is that kind of tribute all that one can ask?

"Kazimir Malevich: Suprematism" ran through September 7, 2003, at The Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum. A related review has more on Russian revolutionary art.