Night Moves

John Haberin New York City

Max Beckmann

One could call it political art, but his allegories never quite reveal their key. One could call it German Expressionism, but he himself would not, and his images rarely give up their sober colors, solid outlines, and mythic past. One could almost call it Modernism, but the tortured narratives, thick bodies, and grim faces scorn such experiments as well.

Max Beckmann had plenty to complain about. He lived through the fall of an empire, the Weimar Republic, and the Third Reich. He saw the human cost of World War I at first hand, as a medical orderly. When the Nazis confiscated and displayed "Degenerate Art," they took more from Beckmann than from anyone else. Ending his career in America, with three teaching stints in as many years, he may even have had to give up formal wear in class.

His disdain for humanity began even sooner, though. As a tight retrospective makes clear, it may well have begun from the moment he encountered modern art. A follow-up review elaborates on his story with a focus on Beckmann's very last years, in exile in New York. Even then he has the same stark technique, sympathy, and disdain, still directed equally at a suffering humanity, a corrupt high society, and above all himself.

History lessons

One can see it from the very first room at MoMA, in its temporary home at MoMA QNS. A beach scene from about 1910 recalls bathers from Paul Cézanne and Cézanne drawing to Henri Matisse, with Matisse and Picasso facing off along the way. In its facing groups, their extended arms, and the blank sea behind them, it also looks to the Henri Matisse of Dance and to Edgar Degas. Degas used exactly those motifs in 1864, for Young Spartans Exercising. Beckmann's brief goes way back—to Modernism at its very source.

He also has a few corrections to make. Compared to Edgar Degas, he clarifies the anatomy. He sharpens the break in perspective between land and sea, pressing his people into a dangerously tight space. He eliminates the nude women, and he makes clear where nudity and pride may lead. In the distance, by the shore, more nude couples are tumbling wildly. I might call the sensibility Spartan, but clearly the Spartans themselves do not cut it.

On the opposite wall, Beckmann adopts the high horizon and long diagonals of a Civil War sea battle by Edouard Manet or, earlier, Théodore Géricault's Raft of the Medusa. The figures, though, packed desperately into lifeboats, are not looking to the distant ship for salvation. They are rowing frantically in the opposite direction. They are fleeing the Titanic, and most are about to die.

Another early painting takes a decorative interior out of Edouard Vuillard or Félix Vallotton. It adds dark colors, lack of communication between family members, and a deathbed theme closer to Edvard Munch than to Pierre Bonnard. Still another work piles broad white strokes onto a brushy seascape out of Claude Monet and Monet in Venice long before the Water Lilies, but as if to parody the near abstract patterns of Gustave Klimt. Either way, the message comes through: the avant-garde just does not take art seriously enough. The urbane circles of Paris and Berlin need a history lesson.

With the destruction, poverty, and starvation after World War I, Beckmann has plenty to teach. In Night, of 1920, one cannot tell the helpers from the torturers. A few bright colors slip like blood through the thick fields of white paint. In another family scene, figures sit elbow to elbow without a hint of mutual recognition. The women bury their heads in their hands or their faces in a mirror. In other paintings and prints, pretty much everyone seems to be descending from the cross.

For now, Beckmann looks more and more to the jagged simplicity of old woodcuts and the imagery of the Bible. The black outlines and white areas grow. The figures tumble from top to bottom rather than into depth. In the compressed spaces and dense compositions, one can feel the actors' claustrophobia—and also a nation's.

Sex and symbolism

Starting in the late 1920s, Beckmann's colors deepen. The green of a harbor, streaked heavily in black and white, becomes downright luminous, approaching Lyonel Feininger. As here, he uses black more as a color. Outlines, in turn, become less self-conscious—thinner, less regular, and sometimes colorful. Human forms take greater shape apart from the crowd.

His cast of characters grows as well. Circus actors degrade themselves as animals. Four triptychs and related single panels introduce more of Germany's past, as Viking sailors and kings. Christian themes fade into Paganism, but they had already lost any hint of redemption. When one woman out for a boat ride holds up her arms in pleasure, her splayed hands echo the torments of Night. One could mistake her gold bracelet for rope binding her to the mast.

His cast of characters grows as well. Circus actors degrade themselves as animals. Four triptychs and related single panels introduce more of Germany's past, as Viking sailors and kings. Christian themes fade into Paganism, but they had already lost any hint of redemption. When one woman out for a boat ride holds up her arms in pleasure, her splayed hands echo the torments of Night. One could mistake her gold bracelet for rope binding her to the mast.

Throughout the 1930s, the men remain violent, brutal, and threatening. Women fare even worse, as self-involved temptresses. A muscular blond rides a man, bound to two fish, like a raft, as serving her needs and her pleasure. Beckman had always looked to the Northern Renaissance, and his Adam, Eve, and the serpent wind around the tree of knowledge as in a scene by Hugo van der Goes. However, in place of an apple, Eve holds out her left breast, while the serpent wears an ass's head. A woman can play even the Devil for a fool.

As in the triptychs, Beckman ditches the painting of modern life for a private symbolism. Scholars struggle over repeated motifs. I always feel much the same sordid mix, of present-day degradation and broken promises from the past. Horns suggests a proverbial horn of plenty amid mass starvation and a prophet amid deaf ears. Fish suggest more food, the miracle of the loaves and the fishes. It also suggests Christ himself, who never does put in a return appearance.

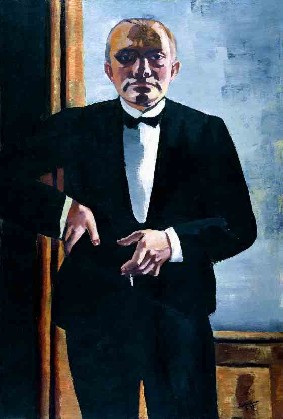

Robert Storr, the curator, prefers to stress their lack of a single, fixed explanation, and Storr has a point: the painter gets to shape the myths. He stands in at once for creator, prophet, and judge. He alone maintains his dignity and decorum. No wonder Beckmann returns so often to self-portraits. He presents a stocky build, stern brows, proper grooming, and never a smile.

Beckmann's thick, round face stares out, but his eyes do not so much as look up, as if he could not be bothered to disdain the viewer. As he stands in black tie, one hand on hip, a thumb and his cigarette point down. He shows affection once or twice, but only for his second wife, Quappi. She, too, dresses in style. In her portraits, the flat colors and black tracery deepen further, like the pretence of stained glass in the paintings of George Roualt. One late Beckmann self-portrait even recalls Matisse.

Masquerades

Beckmann flaunts judgment, and one could in turn pile up an indictment. Call him smug, heavy handed, and obscurantist. In his hatred of modern art and modern life, he does not paint a healthy picture. Like many a preacher, he revels in sin while proclaiming against it. He could definitely use a sense of humor.

Still, Beckmann has more in common with Modernism than he himself might admit, not unlike Ernst Ludwig Kirchner then or another who came to disdain it decades later, Philip Guston in America. His one-sided art also hides some intriguing contradictions. Beckman calls up old myths only to watch them fall apart. He invents new ones only to refuse them a stated meaning.

His modernity includes the unflinching realism with which he faces postwar suffering. It includes the flat surfaces, jumbled figures, and slashing colors. It includes a direct confrontation with the viewer's stare and the viewer's values. Ironically enough, it also includes the idealism behind his rejection of ordinary pleasures. Think of the disembodied dream world of Suprematism or Blue Rider. Think of the obsessive, frightening sexuality in Les Demoiselles d'Avignon and Picasso's women.

Indeed, compared to German Expressionism, "Degenerate Art," Nazi-looted art generally, and the Edmund de Waal family collection, he brings a welcome physicality. That earthy side also suggests a psychic and artistic complexity that he himself fears. Where he sees pleasure, he also sees loathing. Yet inevitably, all that loathing comes with self-loathing as well. When he conjures up a hideous Viking past, he clings to the nationalism that condemns him. When the Nazis called him decadent, I imagine him taking pride in the label.

One glimpses the contradictions in his self-portraits. He may prefer evening wear, but once he dresses as a sailor. It puts him with lowlife along the waterfront. It may put him with his Viking voyagers, too. Even in a tux, though, light and dark confront one another. The line between the brightest white and the darkest shadow descends directly down the middle of the canvas—through his face, his fancy tie, and his downcast cigarette.

He presents life as an eternal pageant in which the actors cling to their masks as firmly as Picasso's Three Musicians or tributes to role-play and African art today. I think again of the woman riding the man to sea. The blue fabric binds her to him as well, and each holds a mask of the opposite sex. Does she turn her finer gaze from the male mask, while he holds the female mask as an idol? Or does the black mask of the other get the last word? It may serve as the only self-image that Beckmann's man, woman, or art will ever know.

Max Beckmann ran through September 29, 2003, at MoMA QNS. A related review looks at Max Beckmann in New York.