Jewish Life and Movement

John Haberin New York City

The Sassoons as Collectors

The Newman Foundation: After "The Wild"

"He paints nothing but Jews and Jewesses now and says he prefers them, as they have more life and movement than our English women." Faced with a stereotype like that one, one hardly knows whether to see an insult or a compliment, but the speaker, a dimly remembered British poet, got this one right.

John Singer Sargent painted one Jewish family often and knew them well. And they were on the move, enough to make their story a pocket history of three continents and the last two centuries. "The Sassoons" at the Jewish Museum begins with persecution and ends amid the trauma of world war. Along the way, it places them in the first circle of half a dozen cities,  as entrepreneurs, creators, patrons, and collectors. If the tension here in inescapable, it underscores the tension among wealth, achievement, and a deeply felt religious identity. And, oh, we do have more life.

as entrepreneurs, creators, patrons, and collectors. If the tension here in inescapable, it underscores the tension among wealth, achievement, and a deeply felt religious identity. And, oh, we do have more life.

So here they come again—a wealthy collector, a lavish gift, and a museum exhibition, to entice the second from the first or to pay the first back for the second. You may deride it as a sell-out or dismiss it as more of the same. What, though, if the collector is the Barnett and Annalee Newman Foundation, established to continue on in the spirit of a leading figure in postwar American art? Barnett Newman presided over Abstract Expressionism and its successors as if they were his personal domain, and he nurtured many an artist along the way. Could he stand as a mentor to others to this day? The Jewish Museum is counting on it, with "After The Wild."

It shares the museum with a family that moved easily among artists, the Sassoons. Newman, though, was not a collector but an instigator. He had a memorial exhibition at MoMA on his death in 1970, but fame and fortune were slow in coming. Annalee Newman kept her job in the New York public school system because a woman should not have to stay home, but also because they needed the money. He called a work Vir Heroic Sublimus, or "man the sublime hero," just as he was catching on for real—and just as the sublime male hero was going out of style. Does that leave room for the foundation and for heroes today?

Pride and assimilation

"The Sassoons" opens in 1830 in Baghdad, with the family patriarch, whose shadow runs through everything. David Sassoon's ancestors included treasurers to the Ottoman governors, but oppression drove him east—to Bombay (today's Mumbai), where he profited from the spice trade, and China, where he found ready markets. He did better still with opium and cotton, supplying nations that blacklisted the American South during the Civil War. The Opium Wars opened port cities to the British and gave Sassoon an entry into British society. His chief heir had a mansion in London, a grand villa north of the city, and a country home at Kent. Winston Churchill (yes, that Churchill) painted its sitting room, with light streaming through a window, enriching its colors while leaving a child in darkness.

King Edward VII called one daughter a close friend and awarded her the Order of the British Empire, but it was not all about status and money. Another daughter edited two major newspapers, quite an achievement for anyone and a first for a woman. The show ends with Siegfried Sassoon, among the most scathing of the British war poets (and most certainly not the English poet who dismissed Sargent and Jews). Being a handsome, distinguished soldier in World War I could not protect him from its horrors. He may have moved John Singer Sargent to break from portraits long enough to paint soldiers on the front line, as his sister Emily Sargent never could. Meant to show solidarity between the British and Americans, at the behest of the government, it shows instead a dim, gray, dejected crowd.

Sargent had his most shocking painting with Madame X, her very name an enigma. The Sassoons were more like chameleons. Does their profiting sound sordid, especially in light of opium and colonialism? They gave a lot back, endowing Jewish hospitals, schools, synagogues, and a library in Asia, but also the restoration of St. Paul's Cathedral in London. They married into Jewish banking families, the Beers and the Rothschilds, but Siegfried was raised an Anglican and died a Catholic, almost fifty years after the art of World War I. And that cannot help raising questions of identity.

Which culture matters more, then, the host or the faithful? Not just Jews struggle with questions of pride and assimilation, with pride having pride of place in progressive politics today. It may pose a stark choice between glorying the framers and pointing to scars that nothing can erase. I have written about what Judaism means and does not mean to me, too. What, though, if the anxious and the critical are asking the wrong question? They might better ask what draws them to America's ideals, what roots them in their past, and how they, in turn, are reshaping both.

The Sassoons sure did in building their collections, including Jewish antiquities. David Sassoon first appears in a turban, but in the style of a Renaissance portrait, and his most exquisite holdings were marriage contracts bearing Hebrew letters but the fine calligraphy of Islamic art. A later generation collected Chinese art and helped fuel a European taste for it, in wood carvings and ceramics. They seemed at home everywhere, except when others turned them out. They never lived in New York, but they moved easily among the cultured there as well. If they had any doubts where they belonged, they could consult always a rare copy of Guide for the Perplexed, by Maimonides, the philosopher and rabbi.

Still, their story is more interesting than their collecting, at least when it comes to European painting. Thomas Gainsborough seems downright penetrating compared to the stiffness in others, from George Romney in the eighteenth century to William Orpen, an Edwardian. Camille Corot and Charles-Francois Daubigny place a house in a sloping, wooded landscape, but without a trace of the crisp light of Corot's Rome. The curators, Claudia Nahson and Esther da Costa Meyer, cannot include selections by Peter Paul Rubens, John Constable, and Gustave Courbet, and one can only hope they did better. Still, there is always Sargent, with his apparent spontaneity and very real glitter. The Met's show of Sargent among friends did not include the Sassoons, but it takes their lives to complete the picture.

Collecting zip

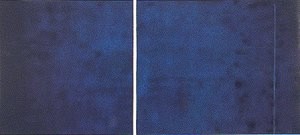

You may have seen Barnett Newman in a photo last year at the Jewish Museum, for "New York: 1962–1964." Artists turned out in droves for a solo show of Robert Rauschenberg, but Newman had a special place at the younger man's right and in his heart. Who else could blow Abstract Expressionism up to a scale that would have challenged anyone—or reduce it to a slim vertical, the "zip"? With The Wild, he eliminated everything but the zip. Its red bleeds out to either side of a blue strip running eight feet tall—the same height as Vir Heroic Sublimus and its Romantic sublime. Rauschenberg would not have been intimidated, but then, as another of Newman's paintings has it, Who's Afraid of Red, Yellow, and Blue?

The museum cannot borrow The Wild but does project it on a wall. It allows one to see the zip as light itself, zipping right along. Rauschenberg would have grasped instantly its modesty and humor as well. After all, zip also means nada. Could its wild mix of stasis and motion have influenced the bands and edges of shaped canvas by Ronald Davis, Richard Smith, and David Novros—or the actual light in neon tubes by Keith Sonnier? Hey, you never know, although Novros in black comes closer still to notched canvas from Frank Stella, who does not appear.

The museum cannot borrow The Wild but does project it on a wall. It allows one to see the zip as light itself, zipping right along. Rauschenberg would have grasped instantly its modesty and humor as well. After all, zip also means nada. Could its wild mix of stasis and motion have influenced the bands and edges of shaped canvas by Ronald Davis, Richard Smith, and David Novros—or the actual light in neon tubes by Keith Sonnier? Hey, you never know, although Novros in black comes closer still to notched canvas from Frank Stella, who does not appear.

All one can say for sure is that, for all his austerity, Newman was open to anything. His zips had to have appealed to Sam Gilliam or Jane Swavely. The black artist had not yet discovered stained, unstretched canvas when he painted his Column Series in 1963. What, though, would Newman have made of art ever since, and what should artists make of him? It is not obvious who selected them. More than half the fifty works date from after Annalee Newman's death in 2000, with more than a few from the last five years.

The foundation provides grants to the living, few of them young, with the expectation of acquiring living work. It also has a healthy relationship with the museum. The curator, Kelly Taxter with Shira Backer, has had her twists and turns, including less than a year as director of the Parrish Museum in the Hampton's (Jackson Pollock country). Before that, though, she was not just a curator at the Jewish Museum, but the Barnett and Annalee Newman Foundation curator of contemporary art. If anything holds this show together, she should know, but what? Like a show last year of collecting abstraction at the Guggenheim Museum, it is about the legacy of Modernism for today—and that legacy is heavily contested.

For one thing, it is resolutely abstract—apart from a graphic novel by Kerry James Marshall, manacles by Melvin Edwards, decorative patterns out of pillows from Amnon Ben-Ami, and hints from Cai Guo-Qiang of a howling wolf. (How better to evoke older Chinese art and to howl against barriers in the present?) Mark Bradford has only dense smudges, not the politics of his response to the Great Migration. Lynda Benglis has no trace for once of knots and flowing dresses. You may think of Peter Halley and Philip Taaffe as the postmodern subversion of everything Newman did, but not here. Meanwhile such artists as Gary Petersen, Terry Winters, Fred Tomaselli, Julie Mehretu, Sarah Sze, and Judy Pfaff throw Newman's restraint to the winds.

For another thing, it treats painting and sculpture on equal terms—for all Newman's quip that "sculpture is what you bump into when you back up to see a painting." Its taste in sculpture runs to blobs, but with coarse, encrusted surfaces. If you are sick and tired of late modern "flatness," you will not find it here. It takes diversity seriously, too. I have already mentioned quite a few African Americans and women in abstraction, but Rafael Ferrer looks to Puerto Rico as well. Seeing Joan Jonas on video in a pig face, balancing on a board while friends dance with empty chairs, I had to think of one last thing—that art is a tough act to follow, and all you can do is not to fall.

"The Sassoons" ran at the Jewish Museum through August 13, 2023, "After 'The Wild" through October 1.