Freeze!

John Haberin New York City

George Segal

For a Jew, a cultural heritage is a living thing. For a New Yorker, even the streets are alive. Thankfully, then, New York's Jewish Museum is not solely in the business of preservation down through the centuries. Along with Jewish history, it has a surprising commitment to the visual arts today.

Still, the museum wishes to do more than to showcase such Jewish artists as Chantal Akerman, Camille Pissarro, or Chaim Soutine and Soutine still life.  It also considers them—or asks that they consider themselves—as Jews. In the case of George Segal, it bought a Holocaust memorial not long ago, and a show at the Jewish museum now pleads the case for Segal as a mirror of itself. Stripped down from a full-scale retrospective elsewhere, it makes him out to be a keeper of America's conscience.

It also considers them—or asks that they consider themselves—as Jews. In the case of George Segal, it bought a Holocaust memorial not long ago, and a show at the Jewish museum now pleads the case for Segal as a mirror of itself. Stripped down from a full-scale retrospective elsewhere, it makes him out to be a keeper of America's conscience.

Unfortunately, that puts more on a perfectly decent artist than he can bear. Conscience may or may not make cowards of us all, but the museum too often avoids confronting what a social conscience might mean in art today. And as the spring term 2011 came to an end, a student ask to interview me about George Segal, the American sculptor born in 1924. As always with inquiries like this, I wanted to be helpful and encouraging without doing his homework for him. I replied that I might be able to help him find his own answers. No, he said, his project really and truly required an interview—and, as a postscript, I want to share it now with you.

Take mine black

Segal always comes off as the humanist of Pop Art. Instead of comics and car crashes, he offers existential despair.

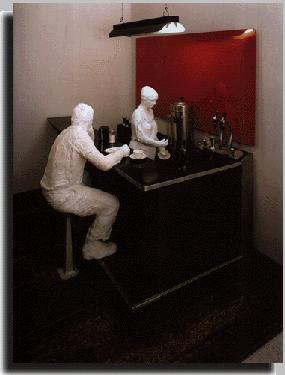

Alone at a diner, a man nurses his toast and coffee, while a lone waitress turns away from his stark meal. Bathed in the light of a movie marquee as if under an x-ray, a laborer stretches to place a single letter almost beyond human grasp. Above him, the blank line waits for the title as if expecting the meaning of life. One hopes the theater is not showing Armageddon.

Pop Art relishes the ordinary, but ordinary people are notoriously absent from much of it. Not from Segal's work, and his trademark body casts make them white as ghosts. Talk about modern art reveling in the concrete. Segal revels in plaster as he sculpts his friends. Covering them in soaked medical bandages, he then uses the figurative casts instead of freehand sculpture.

No doubt fortunately for his subjects, plaster dries quickly, and Segal slathers it on. He gladly accepts its blotchy accretions. The white strips, as loaded as a de Kooning brushstroke, turn gestural painting into Pop appropriation.

Segal places his cold, white actors in real settings, not painted backdrops—a store-bought lunch counter, a cast-off neon sign. Each set, a human artifact now barren of life, contrasts with the inhuman people and the mechanical means used to sculpt them. To view the work, one must step onto the same stage, only to step off again, unable to survive its static rigor and unready to confront the living world it describes. Although I can claim to remain in living color, I come to feel that I belong in neither world, theirs or my own. If an actual lunch counter represents a lunch counter, what then can I represent?

The garish white body casts and the neon's glare merely darken their surroundings, like the insistent white paint of Wayne Thiebaud's bakery counters. One knows somehow that the coffee is black, the toast a midnight meal. Segal may use an instrument of healing, but do not wait for reruns of The English Patient. One can see why his later work includes a Holocaust memorial rather than a tomb for a gorgeous woman and her love. The absence of the sitters and their former imprisonment within both add to the air of desolation.

Politics and the inner voice

Pop Art is notoriously short on conscience, like Andy Warhol at a disco. It derives its kick from a culture moving too fast for reflection. It shows that products aimed at transitory desires can outlive high-toned art, like Styrofoam that refuses to biodegrade. Like Warhol in his car crashes, however, it can get pretty scary for all its cynicism. At his best, George Segal nurses his fears and degradation well.

Yet Segal's deathly silences may sound too sentimental for words, and often I have to agree. The art world almost certainly would, too. I can see why Segal's retrospective began in Canada rather than following, say, Robert Rauschenberg at New York's Guggenheim Museum. To put it bluntly, all art now stands under suspicion of humanism these days, and George Segal acts guilty as charged.

Segal treats conscience as an inner voice. He takes the urban landscape for a universal symbol of despair. Ironically, he thus tends to put conscience beyond politics and beyond place. In the 1990s, just as political art finds a site for rebellion, something seems awry.

Humanists and their Holocaust memorials put guilt up on a pedestal, right alongside heroes. Or so a postmodern critic might say, although an artist like Hannelore Baron might beg to differ. Western tradition and its grand aspirations create fictions, at the price of too much suffering along the way. Art has long served the powerful, and a museum's silence, or a gallery's, is also modern art's way of shutting people up. A few years ago, city workers did manage to knock over one of those sheets of rusted steel by Richard Serra, which blocked their view at lunch. It took a bulldozer and a court case.

Segal's characters alone suggest what he overlooks. The white casts tune out differences of race. As at the diner, his men bow their heads while women turn away. For African Americans, women, and many others today, art's silence has a dangerously precise meaning. Take Cindy Sherman, as the demure librarian from her Untitled Film Stills. As she reaches up, in almost exactly the pose of that man on a ladder, one sees not just a person but an object of desire silhouetting her breasts.

One gets Segal's message right at the exhibition's entrance. In a fairly recent work, of Abraham casting out Ishmael, Sarah glowers and stands apart. Although Segal has also depicted Abraham's taking the knife to Isaac, in a stark bronze at Kent State, here more than the Bible story has changed. There Abraham himself heeds an unseen father's voice and moves to kill. Now all nuances of cruelty vanish in a fatherly hug.

Fringe benefits

And yet art's conscience begins with a single viewer, with the shock and contemplation of a single work of art. Maybe that is why no one can agree just when Postmodernism begins, and Pop Art might be a good place to look. At least half the thrill of late-modern art lies in asking when art first turned on its masters. All art may work that way, in fact, even before Modernism gambled on an avant-garde.

Take Segal as a humanist. Maybe, but what did that big word use to mean anyway? His universal man is trapped is trapped in urban decay and the politics of class. Look again, by contrast, at Pop artists now grandfathered into Postmodernism. Warhol's Marilyn Monroe never saw past the fringes of success.

Besides, Segal's juxtaposition of cast and set adds a harsh irony. If anyone should feel real in Segal's stage sets, why not me? But I have entered the wrong play, and museum-goers cannot touch the work of art.

For centuries, starting with the first cave paintings, art has left humanity's mark on the world. Surely a true humanist should do the same today. Yet Segal's people resemble ghosts in a more palpable reality. If they resemble characters in a play, for them the word cast takes on new meaning.

From the caves on, too, the actors in art's drama have been doers, as hunters and heroes. Segal catches people on the margins before they can hope to act. A man drowns at midnight in a cup of coffee, caffeine's bitter stimulus unable to help. He and the movie marquee suggest that representational art only freezes human gestures. The definition of art as frozen music starts to sound chilling.

Segal's juxtaposition of cast and set helps in another way. It puts his art in liberating touch with the familiar world. Posters have reduced Edward Hopper paintings to existential icons, too, but I can never forget their beautifully realized natural light. In the same way, I run up against that solid lunch counter. The work refuses to abstract experience away. Instead of a pedestal or even Léger's skyscrapers, the man at the marquee perches on a cheap ladder.

Black, white, and shades of gray

Segal's famous contributions to Pop Art, then, can still work. Oddly enough, by slighting them the Jewish Museum wants to make the artist more profound. Instead, it trivializes art that, all too often, is begging for it. The show goes out of its way to stress other stages of Segal's career.

As one might expect, Segal started out as a painter, with all the expressive bravura of a minor Abstract Expressionist. Then came the well-known work of the early 1960s, but after that he again broke the balance between plaster cast and object. First he painted the casts over in tart blues and other bright colors. On top of the bandage swaths, the expressionist brush looks trivial or redundant.

At the same time, as Segal himself prospered, his subjects turned away from people down on their luck. He began a series of portraits, including one of his dealer, Sydney Janis, next to a prized Mondrian. Only Segal's eye for a sitter's personality makes this bearable. I especially like a portrait of Meyer Schapiro, one humanist to another.

Next, he tried inserting his casts in three-dimensional enactments of modern paintings. But the vocabulary of literalism then backfires. Segal has little interest in mind games about plays within a play. He simply reduplicates a favorite work in his special vocabulary of lifelessness. Art may well outlast the ages, but one need not count it among the undead.

Besides, I cannot say I care for Segal's increasingly formalist taste. If I ever begged to be alienated from modern art, I did not have these works in mind.

Most recently, Segal has killed the color at last but kept the paint. He covers entire scenes in monochrome grays. Maybe a mature artist, even an African American, no longer thinks in black and white. Still, without that contrast, he serves up just another representation of the obvious. It hardly helps that Segal has such easy stories to tell. A forlorn line of men and women, for example, signals the Great Depression.

Terminal

Segal's Holocaust memorial shows him at his slickest and least effective. Its body casts, spread out to form a Jewish star, mute the chaos of death. Its barbed wire holds no threat to the viewer, far from the terror of Marina Abramovic's prisons, bodily suffering, and exotic rituals. When he tackles politics, Segal returns it to the history books—or worse yet, to the eternal. One gets the message right at the exhibition's entrance, with that sacrifice of Isaac.

Still, like the selection overall, that curator's choice of opening serves Segal unfairly, and I can never dismiss him altogether. Segal's images take root in my head, and the staging adds a humbling sense of humor. How can I stand apart from it all, enjoying my despair?

My favorite of Segal's works may actually date from not all that long ago. Down at the Port Authority bus terminal, he has cast a line of commuters. Their frozen postures go well with the long waits everyone hates and has come to expect. Perhaps they beg a little too much for attention, but then so do others at the Port Authority, including those in real need. The police have shouted freeze at them often enough, too.

The commuters remind me too of another palpable darkness, the station's upper level, where I often waited to head back to college. Late at night, it functioned emotionally as my own sad diner. I could see why John Barth ended his first novel at a bus station and on the word terminal.

In that one work, the comings and goings of people like me stand in well for Segal's old appropriated sets. Maybe the best thing is to remember those sets whenever one can. That way, even at the Jewish Museum, one can accept the artist's limits—and one's own. As a Jew of sorts, my own conscience starts with at least a mild joke.

One can even better accept the limits of politics in a postmodern age. By reviving an older notion of conscience, the Jewish Museum asks one to recover a history for humanism. Today's assemblages quote the art of the museums cleverly, but not all political art begins with art-world politics. Abraham's embrace—like a last wish from one of Postmodernism's flawed, stubborn, and anxious parents—still holds a moving warmth.

A postscript: Pop Art as theater

What do you consider to be one of George Segal's most prominent masterpieces?

Diner will always be my favorite. It creates so complete an environment, and it transforms the Edward Hopper classic for the loneliness of postwar America. The work of art enters the world, quite as much as a combine painting then or an installation today, but it is also representational. Take the two together, and sculpture becomes its own world. When Michael Fried put down Minimalism as theater, he should have looked here.

Increasingly, until his death in 2000, Segal's settings evoke the New York City of his times. His people at a Walk/Don't Walk light, now at the Whitney, are at both a literal and a metaphoric crossing, and it is one that I can recognize. His portrait of his dealer, Sidney Janis, takes me back to the Janis's lifetime, when his midtown gallery was at the center of art—and when Segal was very much a part of it.

What artists did George Segal influence?

A few years ago, I might have said no one. Casting from life was for hacks like Seward Johnson. Pop Art had come to mean something more anarchic, confrontational, and detached. Warhol insists on the dark side of American culture, in celebrity and electric chairs. Yet even then, it is a culture seen deliberately at second hand. Claes Oldenburg celebrates the present, but only because he is having fun with it.

Segal's practices have more parallels in Europe, where body parts are common in sculpture, but his themes are American. Even his Holocaust Memorial has its place in American ethical life. His sole Biblical allusion similarly invokes the artist's place as a Jew in postwar America. Tellingly, it is used for a memorial to the deaths at Kent State—and, necessarily, to the 1960s as well.

Now, though, Segal's style seems everywhere, although without the personal history or empathy. European sculpture is now common in America, starting with Joseph Beuys. Now, too, quoting art history goes hand in hand with plaster casts of body parts, as with Folkert de Jong, a Dutch artist. Kiki Smith, born around 1954, is a key transitional figure in America.

Who influenced George Segal?

Not surprisingly for someone engaged with politics and ordinary sentiment, his influences begin some time ago. He started as a painter, and his sculpture reflects Depression-era social realism. He had to know Abstract Expressionism well, thanks in part to Janis. Franz Kline stressed the contrast of plain black and white. Willem de Kooning introduced slathered paint and human flesh.

Of course, these are parallels as much as influences, like the blank, almost expressionless people in Marisol, a woman sculptor who exhibited with Janis. So is Pop Art, and Segal would surely have known Rauschenberg's 3D stuffed goat or the Still Life with Plaster Casts of Jasper Johns. Jim Dine, who also showed at Janis, used the body as image for paintings of himself in a robe, but with only the robe visible. Segal would also have known the long tradition of working from plaster casts. He just happens to leave it as plaster. Nothing here is cast in bronze—or in stone.

Much of Segal's influences, too, are literary, social, and political. Unlike others in Pop Art, he makes it hard not to talk about "existential anxiety." One can see some of that in Richard Stankiewicz, with decaying figures in black in sculpture, but San Francisco then was far away.

What was George Segal's impact on the art of his time?

Aside from his influence on other artists, he had a broader impact on culture. History will give more space to other Pop Artists. Yet it is hard to think of someone like Roy Lichtenstein invited to make a Holocaust Memorial or wading into Kent State. It is harder still to think of another artist remembered by a broader public for it.

George Segal's retrospective ran at the Jewish Museum through October 4, 1998. The student's name was Hanna Taormina; Folkert de Jong showed that same month, at James Cohan through May 7, 2011.