Silent Languages

John Haberin New York City

Sarah Charlesworth, Thomas Scheibitz, and Sadie Benning

Itself Not So and Languages of Art

Should art speak for itself? Can it? Many artists beg for silence. Decades after postmodern theory startled or angered everyone, they still blame it for excluding them from the art world, while burying the rest in words. Sarah Charlesworth only seems to agree.

Already in 1978, Charlesworth took a month of front pages from the New York Herald Tribune—and then stripped out everything but the photographs and masthead. She followed it with news coverage of political violence and a solar eclipse, unfolding on newspapers from around the world as if in one glorious event. So was art now free of language? Not on your life, and she spent the rest of her career paring back photography, in order to show how images construct meaning. A compact retrospective isolates images from their origins, like a glossy magazine with only its ads intact but nothing for sale. She is relentless in her distrust of found images, while sensitive to their seductions.

People may argue over whether art takes explaining, but it sure gets them talking. As artists, Thomas Scheibitz and Sadie Benning offer reminders of why, even in the face of silence, critics still speak of languages of art. Yet even text art may leave you at a loss for words. An entire show is about aphasia, the loss of speech or language. "Itself Not So" opposes text, unfolding in time, and art, unfolding in space. Only here both time and space are on the verge of breaking down.

Body doubles

The New Museum calls its Sarah Charlesworth retrospective "Doubleworld," due and proper for an artist doubling over to find doubles. For her, what looks natural might be a body double, and what looks like an object of desire may come into being through the desire of others. Already in those front pages of her Modern History, she is not just appropriating photos, but rephotographing them. As with confessions and beheadings today, terrorists in Italy back then stage and release images to create their own narratives, which then take on a second life in the press—and then a third, fourth, and fifth in politics, individuals, and memory. The exhibition itself relegates the series off to the side, where it shares a room with the last work before her death in 2013, set in her studio. The longest way around is the shortest way home.

The museum opens instead with a still more unnerving display of detachment. Each of the fourteen press photos in "Stills," from 1980, shows someone tumbling off a building, in at least one case hitting the ground before one's eyes. At more than six feet tall, the prints are larger than life, even as the people falling are smaller than in life and on their way to losing it. The grain from enlargement threatens to subsume them all the more, and so does a redoubling that Charlesworth then could never have foreseen, in images of 9/11. Who took these photographs, as passive onlookers at disaster, and who exploited them for pleasure or for profit? Feel free to answer "the artist"—or yourself.

Charlesworth traces her questions to the origins of photography in the mid-1800s. The retrospective takes its title from her 1995 series of old apparatus, old conventions, and what they both saw. In Doubleworld, she redoubles the paired and slightly displaced images of a stereograph, along with the instrument. In Still Life with Camera, an old-fashioned box camera aims at a book, a photograph, and a bottle of wine on the far side of a partition. The book, in fine binding, is The People's Encyclopedia of Universal Knowledge. Charlesworth is reconstructing the construction of vision.

Not coincidentally, the photo within the photo, in a small case for private delectation, is a female nude. Charlesworth belongs to the "Pictures generation," when women were demanding ownership of images of women, as with Laurie Simmons, Barbara Kruger, and Cindy Sherman. "Objects of Desire," from the mid-1980s, draws its subjects from fashion, porn, and archaeology textbooks alike. All might be idols—or fossil tales. Another series isolates women in paintings by Raphael and Piero della Francesca. Still other appropriations slip into their folds like a Renaissance unconscious.

These series discard her grainy black and white for the style of everything to come—isolated objects set against the slick colors of upscale magazines. The object stands out against the monochrome, on display for others unseen. Further doublings add yet another layer of detachment, like a Buddha paired with a black square. With Figure Drawings from 1988, forty prints share white backgrounds within white frames against a single white wall. The series add a chilling elegance, like catalog entries from an auction. At the same time, Charlesworth may finally be falling prey to the power of images.

Maybe she was all along. Still, she comes closer in the end to acknowledging their temptations. She associates the background colors with desires, like red for sexual passion or black for dominance and death. She pares things back to an essence that her intellect refuses, as with prints that fade into shadows. She calls her very last series "Available Light," as if nothing more but the light in her studio remained. For an artist obsessed with why art takes words, she almost accepts a glow from within.

Languages in the plural

Thomas Scheibitz and Sadie Benning have been studying the languages of art. For Scheibitz, they are languages shared by both Cubism and his studio. For Benning, like Rannva Kunoy, they are more postmodern or conventional, like ASL or a military manual.  If the task seems quaint today, why do the results seem so lively? Maybe it helps that neither artist gets all that hung up over little things like grammar. They know that art today speaks languages in the plural.

If the task seems quaint today, why do the results seem so lively? Maybe it helps that neither artist gets all that hung up over little things like grammar. They know that art today speaks languages in the plural.

Scheibitz calls his show "Studio Imaginaire," a nod to both an ideal studio practice and André Malraux's "imaginary museum." As for the language, one work even starts with the letter A. Malraux, the French minister of culture after World War II and author of some very weighty novels, must have felt responsible for western civilization, and his three-volume "museum without walls" made it a public trust. Earlier, Walter Benjamin had spoken of the "work of art in the age of mechanical reproduction," with the aim of taking fine art down from its free-market pedestal. That Marxist stance seems newly relevant after Jeff Koons and the art fairs, if also more futile. Malraux, in contrast, would have had respect for painting even in a digital age—enough to want everyone to have access it.

So does Scheibitz, who packs his paintings with easels, frames, and color charts. His interiors have the clear outlines and sprightly primaries of Stuart Davis or late Pablo Picasso. They suggest a stage set for the artist at work. They also border on abstraction. Malraux's original Musée Imaginaire was of sculpture, and upstairs Scheibitz assembles sculpture from much the same simple components. One can still pick up the pieces of early Modernism, he seems to say, and make them one's own—as both a place in the world and an act of the imagination.

Benning, too, works between painting and sculpture. She paints on fabric or resin stretched over wood blocks, sanded, and reassembled. Her tilings vibrate in red, white, and black. They look almost like military formations, and titles allude to weaponry. If that sounds dangerous, she does not take art's beneficence for granted. Like Benjamin, she places it at the confluence of war and capitalism.

It looks vibrant all the same. With a title like Bathroom People, it is also thoroughly down to earth. Even when she debunks painting most, with a photograph of a similar grid in a street wall, she seems optimistic about art and real estate—perhaps because she could not have seen Hudson Yards. She does not even have to ditch geometric abstraction for street art. Like Scheibitz's, her building blocks are available to all. Assembly required.

Late Modernism claimed a language intrinsic to abstraction, and Postmodernism claimed the need to interpret art in words. Nelson Goodman even called a philosophical justification for looking Languages of Art. Now that "theory" no longer runs the show, painters can stake out languages of their own. Whole shows have run through the possibilities, as with signage in a maze from Gabriel Sierra or photographs as a locus of "sight reading," while Bettina Blohm explores patterns as a process of self-discovery. Scheibitz and Benning differ from them all in not treating abstraction as their personal signature. They would rather get people talking.

Divine aphasia

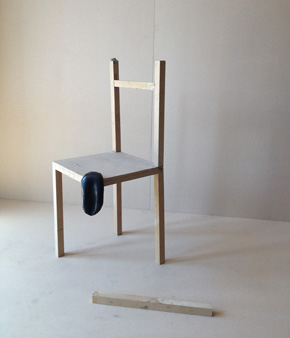

As the physical centerpiece of "Itself Not So," Michael Dean sets a chair, but it does not offer seating to commune with art. Stiff and plain to begin with, it maintains its improbable balance with a slab glued to one corner, where a leg has fallen to the ground. The rough, dark slab seems to be drooping under its own weight. It provides the tongue of the work's title, Analogue Series (Tongue), while the work's geometric clarity provides the subtitle, On the Pronunciation of the Letter L. The curator, Rachel Valinsky, quotes Roman Jakobson on "Two Aspects of Language and Two Types of Aphasic Disturbances." Here existence depends on speech, speech depends on language, and language depends on a falling away.

This is not just one thing after another. You may know Jakobson, the Russian linguist, from the heyday of structuralism and literary theory. You may know, too, his distinction between two figures of speech—metaphor, or one thing in place of another, and metonymy, or one thing connected to another, like the blues for sadness and the blue for the sky. You may find echoes in the opposition of drawing and reading in text art, as in "Drawing Time, Reading Time" in 2013. You may even know that Jakobson saw those principles, of selection and connection, as the bases of meaning in all language. Maybe you had forgotten that he discovered those principles in their loss, in actual patients with brain damage.

The show includes one such patient, in a video by Imogen Stidworthy. I Hate encounters Edward Woodman, a photographer who has lost the power of speech but keeps working.  He is driven to document what he can no longer articulate. (Speaking of the loss of speech, the gallery's explanations are notably lacking.) One sees his lips, ears, and eyes in close-up as he counts to ten. One listens as a speech therapist pushes him to say, "I hate."

He is driven to document what he can no longer articulate. (Speaking of the loss of speech, the gallery's explanations are notably lacking.) One sees his lips, ears, and eyes in close-up as he counts to ten. One listens as a speech therapist pushes him to say, "I hate."

The show keeps mixing images of speech and silence, as in an invitation from the so-called Research Services to submit one's phone number for a call that may never come. It takes its title from a poem by Susan Howe, whose prints reproduce the fonts, spacing, and rhythms of found media, but little else. Archives, she says, are "all we have to connect to the dead," but you know how little the dead have to say. Writers used to speak of "concrete poetry," taking its shape from patterns and not sentences, and Howe's "rectilinear poems" are concrete poetry twice over—as invitations to read and as the impression of an old-fashioned letterpress. Sue Tompkins and Christopher Knowles achieve something of the same weight with a typewriter. The latter's Butterfly Blocks recall Carl Andre, for whom poetry was also sculpture.

Like On Kawara with a telegram, each finds a way to breach the silence. So do Ben Vida and Rick Myers, who first turn text into performance—and then turn the sound waves into images. James Hoff treats the Stuxnet virus, which Israeli intelligence used to sabotage Iran's nuclear program, as a musical score, which he then renders as Chromaluxe transfers. These high-resolution prints infuse colored dye into aluminum, for a fine cacophony of optical activity. With Ryan Gander and Fia Backström, the "social life of media" become sculpture, while Julien Bismuth permutes four painted sticks like those of Cordy Ryman between art and architecture, but as the elements of a language. With Aram Saroyan, a single word stretches into poetry, as Lighght.

Sophia Le Fraga holds a conversation or two, if only with herself. In one video, titled after Eugene Ionèsco's joyful theater of nonsense, a multitasker gets more and more wrapped up in a chat room with someone who may turn out to be a chance encounter, an old acquaintance, or a mirror. In another, W8TING, text messages fly across an iPhone, with no visible thumbs. They sound like Waiting for Godot as performed by teenage girls—and indeed Lucky, the play's otherwise silent character, bursts into a long speech that approaches "the heights of divine apathia divine athambia divine aphasia." Jakobson's patient sounds no less fallen, no less beyond feeling, and no less in the immediacy of the present. "But I am here below, well if I have been I know not, who that, not if I, if that now but, still, yes."

Sarah Charlesworth ran at New Museum through September 20, 2015. Thomas Scheibitz ran at Tanya Bonakdar through December 20, 2014, Sadie Benning at Callicoon through October 26, Bettina Blohm at Marc Straus through December 12, and "Itself Not So" at Lisa Cooley through August 29.