The First Pop Artist?

John Haberin New York City

Stuart Davis: A Retrospective

Jean Tinguely and Max Ernst

Was Stuart Davis the first Pop artist ever? It may not seem that way, for no painter belongs more to New York between the wars.

He captured its streets, its docks, and its elevated trains. He painted its mouthwash and its tobacco. He celebrated its Democratic governor, Al Smith. He worked for the New Deal's Works Progress Administration on art for low-income housing in Brooklyn. He designed murals for Radio City Music Hall and WNYC. He was creating a distinctly American Cubism every step of the way.

Yet those years were also the jazz age, and for him that meant popular song. He reveled in its rhythms, and he built on its idioms until his death in 1964, when Pop Art was a work fully in progress. And he had his breakthrough riffing on packaging, thirty years before painting fell for soup cans and Coca-Cola. The Whitney calls his retrospective, "In Full Swing," and it intends his art to come out swinging. To make its case, it has to pick and choose from his career, but Davis has a further trick up his sleeve. For him, modern art and popular culture were never an either/or—and, as a postscript, Jean Tinguely and Max Ernst were putting the pop and sizzle into Modernism in Europe.

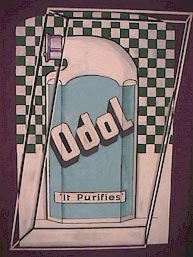

It purifies

Could Pablo Picasso have been the first Pop artist himself? He and Georges Braque made art from smokers and guitars, and they started slipping newsprint into painting in 1913. Journal, or newspaper, could become just JOU—an allusion to gaming or just plain cheek. Yet they also had a past culture's violins and harlequins, and they had their eye more on artists and the dizzying fictions of art. Besides, they were restless and moved on. Stuart Davis went all the way in embracing a wider world.

That mouthwash was Odol, the first to be commercially sold, and the fashion for mouthwash began just after World War II—perhaps in response to the war's disturbing the promise of a civil society. Is it a coincidence that other responses included the assaults of Dada in Europe, the Russian Revolution and Suprematism, and a newly independent American art? When Davis painted Odol in 1924, he incorporated its slogan: It Purifies. The words could well stand for formalism in art, with no room for impurities like text, illusion, realism, and decorative packaging. Yet Davis made use of them all.

For the rest of his life, he was still working through the tension. He wanted an autonomous art, the Whitney notes, but also a popular art with the burden of social responsibility. He wanted a socially conscious art, but he kept it jazzy, upbeat, and experimental. His public murals have his most boisterous compositions and not a trace of the Depression, when his sales plummeted, and his tribute to Governor Smith is at home with the political machine of Tammany Hall. When the American Artists' Congress endorsed Stalin's invasion of Finland in 1940, he stepped back from left-wing activism and devoted himself to painting. He ended close to abstraction.

Davis did not discover the tension all at once. Born in 1892 to two artists, he inherited their admiration for Robert Henri and early American Modernism—really a somber realism with splashes of color. The shock came with the Armory Show of 1913, which exposed him, a future dealer for Davis in Edith Halpert, and so many others to European Modernism. The Whitney does its best to make him contemporary, by starting its retrospective with the packaging. It also gives serious weight to his work after World War II, unlike past retrospectives or a show of Stuart Davis drawings in 2007. Even then, he was adapting Cubism's fragmentation and Fauvism's color to America.

Packaging already announced a free spirit, but otherwise those early paintings have a muted tone. He had to take to the streets to realize where he was going, with a boost from the Whitney. An early member of the Whitney Studio Club, with Edward Hopper, he had his first solo show there in 1926. With a stipend and purchases from Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney, he finally made it to Paris and the art that he admired above all. He hung out in cafés and introduced himself to Fernand Léger, who introduced him to more colorful shapes and larger rhythms. One of his last paintings remembers that year, with the inscription '28 France.

Otherwise Davis stuck to the company of expatriate artists like himself. He learned little French, and it must have been a relief after fourteen months to apply what he had learned to New York. He returned to a city of garage lights, gas pumps, coal towers, and utility lines. He sought "new materials, new spaces, new speeds, new time relations, new lights, and new colors"—and to him that meant America. As an inscription on a late painting has it, Lines Thicken. Already with the still lifes, he included light bulbs and radio tubes. Now he could move from modern technology to the city in which it thrived.

Between the wars

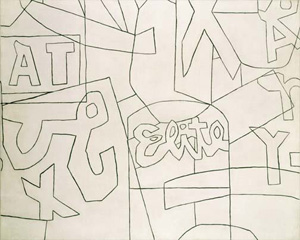

From his age alone, he belonged to the 1920s and 1930s while spanning much of a century in art. He was younger than Charles Demuth and Charles Sheeler, but he shared such subjects as warehouses and utility poles with their Precisionism. He was younger even than Georgia O'Keeffe by four years, but he, too, took on the passage to abstraction.  Cubism taught him to place text on a par with painting, and the interchange ran both ways, with scribbles in place of clouds. His rolling papers for tobacco, Zig Zag, lent their brand name to his work, but not only as product logo. Guess which direction his brush ran.

Cubism taught him to place text on a par with painting, and the interchange ran both ways, with scribbles in place of clouds. His rolling papers for tobacco, Zig Zag, lent their brand name to his work, but not only as product logo. Guess which direction his brush ran.

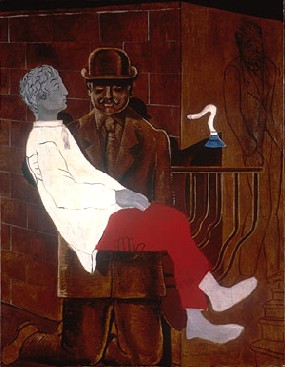

While Davis was older than the Abstract Expressionists, he counted several as friends. The curators, Barbara Haskell and Harry Cooper of the National Gallery, Washington, with Sarah Humphreville, identify the four figures in American Painting, begun in 1932 but completed only in 1954, with himself, Arshile Gorky, Willem de Kooning, and John Graham—not that one would know it. The rough X across one figure may refer to Gorky's early death. Gorky, in turn, credited Davis with making art "clear, more definite, more and more decided." That describes well his bolder, cleaner version of Cubism. It may also help account for why he never adopted the drips or gestures of Abstract Expressionism.

He did indeed live to see Pop Art, although he never cared for it. He had been there, done that. László Moholy-Nagy had designed ads at the Bauhaus, but Davis in the early 1920s thrilled to them. He brought them into collision with the picture plane and the viewer. He did not adopt Ben-Day dots like Roy Lichtenstein, but he did adopt dots and stripes as wallpaper and embellishment from the first. Come to think of it, he anticipated the Pattern and Decoration of more recent years as well.

His last decade brought a reduced palette and a closer approach to abstraction, with bright forms set against monochrome backgrounds but far less of his characteristic red, white, and blue. The change may reflect a physical weakness that demanded simpler means, an urgency in the face of death, or an awareness once again of the art around him. Expressionism was giving way to color-field painting and Minimalism. A visceral version of both was on its way then, too, with Frank Stella. With his last painting, Davis added Fin (or "death" in French) the very day of his death. He ended as he began, with a style spanning decades in search of the present.

He had his mind games, with imagery and text. As early as 1931, he added Front to the front of a building. Still, his art was more joyful than subversive. He hated the title that Radio City gave his mural for the men's smoking lounge (soon after losing his first wife), Men Without Women, but he filled it with symbols of masculinity, such as a pipe and barber's pole. Cubism may have been reality reassembled, but he could disassemble reality only so far. What often looks cut and paste is painted, not collage. If you see masking tape, which he often used to firm up the edges of underpainting, odds are that the work is unfinished.

His thoughts kept returning to the jazz age, not unlike Herman Leonard, Archibald Motley, and Romare Bearden in Harlem. He compared his work in series, such as variations on the logo for Champion spark plugs, to improvisation. Titles like Report from Rockport or Owh! in San Pao even sound like pop tunes, and one squiggle resolves into actual handwriting: It Don't Mean a Thing If It Ain't Got That Swing, after Duke Ellington. Still, this is jazz as not an avant-garde, but an environment. Davis has entered history as, like Al Smith, the happy warrior.

Homage to self-destruction

Who knew that the end of art would be so much fun? When Jean Tinguely set off his Homage to New York, he came as close as art can to fireworks—but not the kind that stirs memories of summer evenings, cold beer, and the American dream. Not that the title is altogether ironic. The sculpture went on display at the Museum of Modern Art in 1960, when the museum and 1960s New York were doing as much as anyone to keep Modernism alive. Frank Stella had displayed there in "Sixteen Americans" only the year before. Yet it promptly destroyed itself, barely sparing its neighbors in the sculpture garden. Tinguely, still in his mid-thirties, meant to go out in a blaze of glory, along with the prospects for modern art.

Somehow, though, he kept going, often in collaboration with his wife, Niki de Saint Phalle. History may assign his Nouveau Realisme, as the movement called itself, to that one day in March, but his ramshackle constructions fill one of Chelsea's largest galleries. They cover the thirty-five years until his death in 1991, and not one of them is hastening to an end. The crowded display even puts them on a raised platform, like, well, art. A handful keep going, driven by motors rescued from old record players and their collective indignity, and one can depress a foot pedal to trigger the remaining sculpture at will. Light bulbs go off figuratively and literally, wheels turn and feathers wiggle, an army boot threatens a swift kick, and shears cut the air—but nothing, not even a large chandelier, will ever crash to the ground.

Homage to New York did not last long, but then neither has the shock of the new. Tinguely looks back to the assimilation of anti-art and the avant-garde as far back as Dada. He was, after all, from Switzerland. His junkyard also provides a handy bridge from Robert Rauschenberg to trashy installations today. He even anticipates the epic marvel of self-destruction in The Way Things Go, by Peter Fischli and David Weiss. George Rickey had his kinetic sculpture and Alexander Calder his Calder mobiles, but neither was so eager for others to play along.

Homage to New York did not last long, but then neither has the shock of the new. Tinguely looks back to the assimilation of anti-art and the avant-garde as far back as Dada. He was, after all, from Switzerland. His junkyard also provides a handy bridge from Robert Rauschenberg to trashy installations today. He even anticipates the epic marvel of self-destruction in The Way Things Go, by Peter Fischli and David Weiss. George Rickey had his kinetic sculpture and Alexander Calder his Calder mobiles, but neither was so eager for others to play along.

Max Ernst outlived his self-destructive streak, too. The artist who began by confronting madness and left a lover, Leonora Carrington, with a nervous breakdownturns out to have aspired to myth. And in his hands, myth came to look like child's play. "Paramyth" contains more than a dozen sculptures from 1934 to 1967, in such lasting materials as cast bronze and limestone. Many have the biomorphic elegance of sculpture from Henri Matisse to Constantin Brancusi. They are also a good deal cuter.

The show's title may mean that Ernst worked alongside myth rather than within it, although one work alludes to Oedipus. Yet it might be better to say that he worked alongside modern art. A gifted painter, he ran into shocks of his own in both art and life. He took an early interest in abnormal psychology and, like an entire generation, found the same darkness in supposed civilization after World War I. Work from those years looks like what Paul Klee called his Twittering Machine, only far more ruthless. Surrealism freed him further to pursue personal histories in painting and collage. "Paramyth," too, concludes with a touch of autobiography—a slim figure abstracted away from Dorothea Tanning, his wife and herself a prominent Surrealist.

The show looks uncannily alive but also uncannily settled. Like Tinguely, Ernst found inspiration in junkyards, with what might pass for manhole covers, but also in child's play. Figures smile, and many look like toys. A chess set really ought to become a classic in use. Designed in 1944 for an exhibition on the imagery of chess, it surely pays homage to Marcel Duchamp, art's most famous player and most noted abandoner of art, and to New York. But then chess, too, is only a game.

Stuart Davis ran at The Whitney Museum of American Art through September 25, 2016. Jean Tinguely ran at Barbara Gladstone through December 19, 2015, Max Ernst at Paul Kasmin through December 5. A related review looks at Stuart Davis drawings.