Opening the Gates

John Haberin New York City

Willie Cole, Deborah Grant, and Maureen Kelleher

Galleries can be intimidating places, maybe especially for an artist and an African American. Willie Cole, though, welcomes you in. He leaves a wooden gate wide open, with a pair of lawn jockeys to show the way.

With luck, the art world can be open to African Americans—and African American art can be open to almost anything. Deborah Grant identifies with those who have suffered, whoever you are. From her work at the Drawing Center, one might well mistake her for an observant Jew. Meanwhile Maureen Kelleher combines art with a white woman's quest for justice for African Americans behind bars. It is hard to talk about their art apart from biographies, only starting with their own. But then a gate is still a gate, just when you thought that you had already made it past the doors.

Guiding spirits

Then, too, a lawn jockey is still a lawn jockey, benevolent but subordinate. Its black, red, and white are an embarrassing reminder of racism in America. Even before the gate, another jockey is taming a horse on canvas, and one can only hope that the treatment will not extend to you. Other jockeys like him do their duty on canvas, in one case framed by a battered and scavenged double door. Plainly Willie Cole is fond of doubling, and other spirits inhabit every corner of his universe. The lawn jockeys remind him, if maybe not you and me, of the Yoruba religion of West Africa. Elegba, a messenger of the gods, governs nature, yes, but also serves as a guardian and a guide.

Cole speaks not just of "links between worlds," but of a true "world culture." I think just as much of how the past inhabits the present. So long after the Civil War and the Civil Rights Act, this world has room for big hopes and deadly tensions. But then, as the show's title has it, "If Wishes Were Horses . . ." Cole's art embraces ambiguity, although not in the sense of irony or a loss of meaning. He just wants you to connect.

Take your time. Wall sculpture may look like garbage, before it coalesces into a scarred face, a defiant black sticking his tongue out, a Cubist portrait, or an African mask. For those who think of African deities as "fetish objects," it is also an assemblage of high heels. Women's shoes serve as well as materials for the show's centerpiece, The Sole Sitter—another wisher and an artful pun. The black crouched figure has its elbows on its knees and its hands raised in contemplation, confusion, weariness, sorrow, or dreams. Its feet are its least fashionable element.

Cole has been making connections for some time. Long before a residency at the Studio Museum in Harlem in the mid-1980s, he was a ten-year-old in Newark taking art classes while playing with toy soldiers. Connections for him are like riffing, with motifs that keep giving. A household iron attests to the warmth of flesh tones, but also the branding of human flesh. It belongs to a woman's world of craft and design, much like the high heels. Yet it belongs as well to Dada and Surrealism, when Man Ray studded an iron with nails and called it Gift.

Riffing is itself a hallmark of both non-Western cultures and modern art. In The Savage Mind, Claude Levi-Strauss called it bricolage (from the French for tinkering), or making do with things at hand. Introducing Cole's 2006 retrospective in Montclair, New Jersey, Patterson Sims recalls a directive from Jasper Johns. Like Johns, Cole is happy to "take an object," "do something to it," "do something else to it," and then some. For Johns, an iron left an impression in encaustic. For Cole, it has led to his most searing work. Then again, I never really got off on high heels.

Cole has one iron construction in the gallery's office, but mostly he has set aside the ambiguity and the dangers. His most explicit image of suffering, Jesus strung up on a guitar, turns the Crucifixion into a spiritual. Maybe riffing is hard to sustain forever. Maybe, too, Cole feels the force of a greater welcoming. In his largest work, a chandelier of two thousand water bottles, their red plastic collects the light. Is it another guiding spirit or the recipient of a dream?

Easy as pie

How many artists have exhibited at both the Studio Museum in Harlem and the Jewish Museum? When Deborah Grant appeared at the latter in "Reinventing Ritual," an unfocused show of some sixty artists and designers, she must have welcomed the need for reinvention. Now she tells of perhaps the archetypical sufferer, with "Christ, You Know It Ain't Easy!!" No, not John Lennon, who sung those words and "they're going to crucify me," in what became the last Beatles song to top the charts. Nope, the other guy—the one in the title.

When John recorded "The Ballad of John and Yoko," he sounded awfully self-aggrandizing. No matter. He had Paul, another generous soul, on bass and drums while George and Ringo were on vacation. Grant clearly knows better, too, when she rubs the point in with two exclamation points. A degree of humor and self-mockery is one of her strengths, and it persists through all her identification with others. The five drawings in Easter's Best introduce Jesus in a white suit as if for his bar mitzvah or a Vegas act, his best friend John (the disciple, not the Beatle) as a cool black dude, Mary Magdalene as less a reformed prostitute than an overbearing Jewish aunt, the mother of God as the nightmare of a Jewish Mother, and the third Mary as not much better.

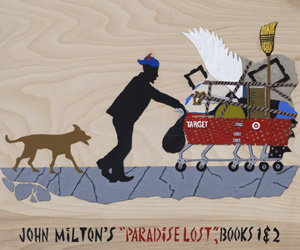

God's Voice in the Midnight Hour begins with Yeshua, on the way to his passion, but Grant cannot resist a digression here and there, in a wandering tale of hope and betrayal. Both sides in the Mideast conflict enter on equal terms, but so does the specter of a Nazi banner. The Resurrection turns up barely a quarter of the way through the twenty-four birch panels. So does "the apprenticeship of Debbie Kravitz"—in which Grant, born in Ontario and raised as a Catholic in the diversity of Coney Island, manages sympathy for a bent orthodox Jewish male haunted by a full moon and taunted by black kids in silhouette. (The line refers to The Apprenticeship of Duddy Kravitz, the 1974 movie with Richard Dreyfuss as a poor Jewish boy and a bit of a hustler in Montreal.)  Milton's Satan pushes a homeless man's shopping cart, and Jesus at Gethsemane beneath a crescent moon becomes testimony to a "schizophrenic's belief in the burning bush."

Milton's Satan pushes a homeless man's shopping cart, and Jesus at Gethsemane beneath a crescent moon becomes testimony to a "schizophrenic's belief in the burning bush."

Grant lets no one off the hook, not even her fellow African Americans, while welcoming every conceivable outsider. Her bare wood, silhouettes and bright colors, and cutouts relate at once to Henri Matisse, woodcuts, illustrated Bibles, artist books, African art, Florine Stettheimer, and folk art. The show's centerpiece in fact imagines their meeting. It describes Mary A. Bell, a self-taught artist, Catholic, and African American who reached the end of her life in 1941 in a mental institution in Boston. According to the curator, Claire Gilman, Bell believed herself to be the instrument of God. Crowning the Lion and the Lamb tumbles across six feet and four panels, past the stern eye of Matisse, as she encounters Gertude Stein, a marquee for Gone with the Wind, and an exhibition ten years after her own death, only to awake where she began.

Her show's title notwithstanding, Grant makes it look easy, and that can make her at times a little slippery. When she appeared in "30 Seconds off an Inch," a show at the Studio Museum of "conceptual art and identity politics," she eluded either label. When she appeared among the emerging artists in "Freestyle" at the Studio Museum in 2001 and then in the 2005 edition of "Greater New York," at what is now MoMA PS1, she almost faded into the crowd. She calls her imagined encounters with the past "Random Select," a hint at both their constant striving and their clutter. She pastes much of her text in twelve-point type too high to read—and she hardly minds, for the meeting of so many characters and identities is all a dream. This version of outsider art embraces multitudes, and you would be foolish indeed to turn away.

Grant's fourth wall looks to both Old Testament and New, with the outlines of flaming oil lamps like those that persisted through the long nights of Chanukah, filled with colorful symbols of Jewish faith. Maybe they could have served in the kitchen for Ferran Adrià, the subject of the Drawing Center's main event. The Catalonian chef, whose pilgrimage restaurant is set to reopen as a "creativity center," designs his own kitchenware, as well as molded templates for food "drowning" in mousses and caviar. Here his drawings decipher the "genome" and "genealogy" of cooking, creativity, and Dom Perignon. If one wants someone to blame for turning small portions into 3D compositions, pay a visit, but plan to go elsewhere for dinner. It takes an artist like Grant to thrive on a spare meal.

For life

When someone devotes her life to prisoners sentenced for life or to death, she is giving voice to the dreams of others through her own. One could say the same of artists. Remarkably, Maureen Kelleher manages both roles. An army brat who found her way to activism, she has worked for twenty years as a private investigator for defense attorneys. Mostly that means returning to homicides years after a conviction—to what go by the chilling term cold cases. When René Magritte called a painting On the Threshold of Liberty, he had no idea that lives were at stake.

Presumably an investigator takes, above all, a listener, and her art is filled with words. Some are on scraps of paper, pasted onto wood salvaged from shipping or refuse, like the materials for Louise Nevelson, Martha Clippinger, or a young Robert Indiana. Mostly, though, she carves into the wood, leaving something close to scars. When you read "abandoned, betrayed, chaotic, disoriented, ignored, manipulated, unloved, worthless, tired," you feel it. Often as not, collage becomes an impromptu tiling, the elements set off by paint or fabric, like and Mary Lee Bendolph and Gee's Bend quilting. They also become frames or windows for portraits out of photographs and old newspapers.

Kelleher lived in New Orleans until leaving for New Jersey a step in front of Hurricane Katrina, and she dedicates her show to Herman Wallace—who spent an unconscionable forty-two years in solitary in Angola, as it came to be known, the notorious state penitentiary in Louisiana. However, her work is not the illustration program for her day job, and its stories extend well beyond prisons and what a later show calls "Due Process." More precisely, they do and they do not, given the twists and turns of African American history. When she surrounds a large Latin cross with yellow Caution tape, the warning connects police barriers to spiritual ones. Her most frequent subject is James Baldwin, whose words pushed her to start making art in 2001. "Does the law exist," she quotes from him, "for the purpose of furthering the ambitions of those who have sworn to uphold the law, or is it seriously to be considered as a moral, unifying force, the health and strength of a nation?"

Kelleher takes on the appearance of folk art, but not to assume the mantle of "the primitive." Besides a writer as sophisticated as Baldwin, her characters include Beauford Delaney, the modernist and a friend to Baldwin, along with Harriet Tubman and (think about it) a monkey. The tiling includes abstractions, as if Piet Mondrian had worked in miniatures. The biographies also include outright inventions, like that of a black maid and mother figure to Gustav Klimt. The materials simply add a sense of continuity and history. The paint's warm tones could often pass for weathering.

If it seems unsettling to find a white artist appropriating black history, put it down to her commitment. Her work habits extend to a show of some forty large and detailed paintings. Her histories do, though, include family. She accompanies photographs of her father in uniform with a memory from age thirteen: "Just don't bring home a nigger." A second version alters the last two words to "the next president of the United States."

If that ending sounds hopeful despite it all, Kelleher is like that. She calls her show "Tender Strength All Around Me," for once entirely her own words. She even thinks of Wallace's long years in solitary as a tribute to endurance and survival. "Some of you will slouch away," another text reads, but "some of you will come out of this alive." She could again be expressing the dreams of others. She could also be challenging the viewer to hear and to see.

Willie Cole ran at Alexander and Bonin through November 16, 2013. Deborah Grant and Ferran Adrià ran at the Drawing Center through February 28, 2014, Maureen Kelleher at Sylvia Wald and Po Kim through March 15.