From Here to Eternity

John Haberin New York City

Louise Nevelson

In 1959 the Museum of Modern Art opened its most influential show since "Picasso: Forty Years of His Art" twenty years before. The New York Times greeted it with its customary disdain for the new. John Canady called it "sixteen artists most slated for oblivion," but still it was quite a cast. With "Sixteen Americans," Dorothy Miller reasserted the museum's commitment to emerging art. In the process, she all but defined the next two decades.

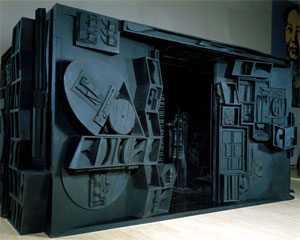

One artist was twenty-three and just out of Princeton. And one, Louise Nevelson, was born in the previous century. Nevelson, who died in 1988, already knew oblivion. She had been laboring under it for sixty years. With her black and white chambered sculpture, built from discarded fragments of wood, she also made it her subject matter. At the Jewish Museum in 2007, she receives a welcome retrospective.

Oblivion is a big word, and much of her work may already appear too monumental or freighted in mystery. One iron assemblage looms over Park Avenue traffic only blocks away. Her retrospective, though, shows her on a more intimate scale, until her sense of time feels almost natural. It also explains why a woman born in 1899 had so much to do with art after 1960. As a 2015 postscript, so does Nevelson's collage. It shows how wrong it is to compartmentalize her as an artist or woman—all the more so as she knew when to do it herself in her art.

Mrs. N's dream house

Miller titled other shows, too, by simply the number of artists. Compared to the latest Biennial (then an Annual) or "Greater New York" today, make that a very small number. The Modern intended to create a canon for modern and contemporary art, not a survey. For all the triumph of "Sixteen Americans," it could not do so much longer. In fact, 1959 might have been the last year one could take modern and contemporary art as obviously the same, for all the appeal of New York in the 1960s. With that twenty-three year old, Frank Stella, MoMA may have found its last canonical artist, just as Pablo Picasso was its first.

In other regards, however, Miller presented a kind of antidote to its great earlier show. When MoMA brought Picasso to America, it taught a lesson in European art. Now Americans lay claim to modern art. Picasso had invented a vocabulary for Modernism. Now artists spoke a foreign language.

Stella, Ellsworth Kelly, Jasper Johns, Robert Rauschenberg, and other artists in that show do not construct Cubist spaces or Surrealist mindscapes. Stella and Kelly introduce geometric abstraction and look ahead to Minimalism. When Johns and Rauschenberg create a messy combination of art and life, Pop Art is already on the horizon. Roy Lichtenstein cartoons, Andy Warhol, and Warhol silkscreens lie just two years away.

Geometry and Pop Art may seem at opposite extremes. Yet Leo Steinberg's term for the picture plane in Johns and Rauschenberg, the flatbed, applies quite well to Stella's or Kelly's early work. Stella paints Die Fahne Hoch, the flag on high. Johns paints Three Flags.

Louise Nevelson fits just fine into this story—up to a point. Stella has his black stripes, and Johns has his White Flag. Nevelson has two bodies of work, in black and white, with separate studios for each. She constructs large work from foot-tall boxes that would do Donald Judd proud. Their shallow depth thrusts the picture plane against one's face, like Johns's targets and Stella's fearful symmetry. They fill the room, much as Minimalism came to adopt the surrounding space.

They shun illusion, and they recycle household items, like Rauschenberg's "combine paintings." She scoured the sidewalks, trash heaps, and furniture factories. Chair legs and other scraps fill the boxes, and their vertical lines reinforce the grid. They are the material of life, but not images of the living. When Nevelson calls one small work her Dream House, she has built a literal house as well as representing one, and she has given it everyday furnishings. If the empty house and its totems seem a little creepy, so do Johns's plaster casts.

Member of the wedding

Nevelson came into her own with these works. They mark her forever as an artist of the 1960s and 1970s. However, she sticks out amid those young Americans, because she brings so much of the past. Each box differs from its neighbors, without a hint of symmetry. Her shallow, shattered space still derives from Cubism. Her dream houses and their ghosts extend Surrealism.

Nevelson has little concern for the immediacy of the American century, with its trust in raw experience, television, and the headlines. For Nevelson, staring at oblivion meant reaching for eternity. She takes the long view. After so many years and so many different lives at odds with her environment, she had to.

Born a Jew in Ukraine, Leah Berliawsky became a picture-perfect American. She grew up in New England, where her father, a timber merchant, continued his trade. If her work contains a kind of biography, it is in the wood. She married into wealth, moved to New York, and took on the role of a proper wife and mother. Then she started over. She enrolled at the Art Students League, studied like Jane Freilicher with Hans Hofmann, divorced, and made herself a modern artist.

In her own account, she saw herself as a sculptor from childhood. In practice, she switched from painting to sculpture only after another ten years, in 1940. The Jewish Museum displays a standing nude that could have come from any of a dozen well-known Cubists. However, she gives the hips more mass and more of a turn, stacks both breasts on one side opposite a massive half chest, and calls it Self-Portrait. She could be insisting on a woman's independence and self-assertion. She could also be exploring a deeper consciousness, with room for the male alongside the eternal feminine.

One can see those themes again and again, culminating in 1959, with Dawn's Wedding Feast. The attendants line two walls, with the wedding couple at center. In this ceremony, both bride and groom dress in white, transcending gender. Perhaps the artist has improved on her own society marriage. The work ended up in nearly twenty pieces, in thirteen separate collections. Beautifully, her retrospective brings them together.

Soon after the self-portrait, another work already points to her other side, in Surrealism. Moving-Static-Moving Figures, from 1945, also introduces her thinking in series, another habit that feeds her later assemblies. The seven figures again resemble Cubist sculpture, but curves embellish their skin. The incisions hint at lips or anatomy. They also free her imagination from the Cubist grid. One can see the same imagery and impulse in later titles like Black Moon.

From Surrealism to assemblage

She starts scavenging even before 1950, when the first box appears. A pair of andirons, freed of their decorative function, become griffins again. The scavenging also helps to clear some of the baggage of past art. Scrap wood reduces the elements to rods and planes. Again the process of sculpture propels her toward the 1960s.

The year 1950 could also stand for a new American art. That year brought Number 10 by Mark Rothko, Excavation by Willem de Kooning, and Autumn Rhythm by Jackson Pollock. And one way to pin that art down is as an overcoming of the opposition between Cubist form and the Surrealist imagination. Nevelson found herself part of a New York scene. Lee Krasner started her studies with Hofmann just four years after Nevelson.

David Smith, the best-known Abstract Expressionist sculptor, develops in close parallel to Nevelson. He works his way through Surrealism both by "drawing in space" and by composing objects in three dimensions from planar views. Where she liked workshop parts, Smith later used his workbench as a motif, its tools intact. Her Chief, from 1955, reminds me of a giant Swiss army knife. Smith and Nevelson also borrowed the same term for their standing figures, Personages.

Smith, whom Clement Greenberg deemed the only major American sculptor, served as a welder in World War II. He also made brutal images of war. Nevelson gave yet another explanation of her preference for wood: adopting metal during wartime would have profaned the sacrifice of those overseas.

Remarkably, she still had one giant step left, and MoMA caught her right on the cusp, first with "Sixteen Americans" and again with "The Art of Assemblage" in 1961 alongside Bruce Conner. She now let the grid multiply and the sculpture grow, to the point that one can no longer count its parts. Its boxes and planes bar the eye. Sculpture as freestanding form in space extends beyond wood, to the room itself.

She became a public figure and a public artist, with outdoor sculpture like the piece on Park Avenue. She painted a few pieces gold, which emphasizes their decorative side and even flattens them further, but looks mighty tacky. She experimented with clear plastic, in work that only a hard-core Minimalist could love. All this time, though, part of her clings to the past. Her spooky sculpture, with seemingly a life of its own, has a lot in common with work by another woman artist of the 1960s and another European-born Jew, Eva Hesse. However, she could not approach Eva Hesse in her materials, stricter repetition, and wilder variations.

Whoo-ee!

Nevelson never really abandons the human figure. She never abandons its haunts, in empty chambers at night or in eternity. She presents a wall as a pageant, even if one cannot distinguish its individual personages. She wants her myth making, with titles like Goddess from the Great Beyond. She needs her scale, because she still takes the long view.

A work like Mrs. N's Palace has multiple scales. The units add up to an entire room within the gallery, with a visible entrance of its own. One can circulate completely but not enter, just as the eye cannot penetrate her objects in a plane. The work announces its scales on many levels, from its size and its relation to the gallery to the number of boxes and the countless objects lining them. In turn, these elements in space correspond to so many scales in time—the time it took her to find and to assemble them, the time it takes the viewer to walk around them, and their hundreds of prior histories. The experience of the work unfolds in the museum and in a deeper space and time.

Nevelson gave the work's date as 1964–1977, thirteen years but several centuries too late for a palace. She was being realistic, even modest, but here, too, she asserts a sense of scale. All this reaching for eternity risks pretension. After the open spaces of Minimalism, her work can look too wrapped up in itself and the past. Moreover, none of the visual detail means much on its own. I keep wanting to put a thumb in each ear, wave my fingers, and screech in mock horror.

She invited this kind of criticism with her public persona. The aging diva came equipped with flowing head scarves and huge false eyelashes. However, her retrospective presents her without the pose, and it pays off. It pulls her work off the public plazas, so that one can linger over the texture of paint on wood. It puts her back into her history, as an artist and as a woman. Taken together, her sculpture appears as more than static monuments and totem poles.

The installation helps, too, by allowing the sculpture's defining and supporting walls to shape the galleries. A work echoes its own process of construction. Objects define extended walls, which then defines an installation in space. Art creates its own intimate environments. In the largest, one can feel at home.

A sense of the past has its advantages. Like Louise Bourgeois and other "bad girls," Nevelson thrives on her position between Minimalism and Surrealism. After her retrospective, however, she looks almost contemporary. When I see the scale of her accumulations, I think of Chelsea installations now. When she uses her large numbers to commemorate the Holocaust, in Homage to 6,000,000, the wall units make me think of a lost library. Another Holocaust memorial cast from bookshelves, by Rachel Whiteread, will never look the same again.

Compartments of the mind: a postscript

Nevelson was the woman, along with Jay DeFeo, among the men that MoMA anointed in 1959—the older woman, the Soviet Jew born in the previous century, the one in the scarf or a hat. She was dark, brooding, and totemic, much like her monumental art. She was the one clinging to eternal mysteries amid the presentness of Pop Art and formalism. For others then, as for Frank Stella, "what you see is what you see," but for her what you see is what you fear to remember. And then she had her literal compartments, those wall units crammed with all manner of wooden objects in black or white. They came from everywhere, and sometimes they returned to city streets, too, as public sculpture.

Nevelson's collage threatens to burst out of those compartments. Not that it abandons sculptural presence. The show has room for a large wall piece from the 1980s, in pitch black, and before that for dowels and other carved wood. Even before that, a large swatch of crumpled metal expands outward as if filled by a deep breath. The earliest and flattest, in paper and cardboard on panel from between 1956 and 1959, has acquired box frames and protective glass that she almost surely never intended, but it seems to belong. Better still, it dares one to see her work as collage from the first.

One can see her roots in Cubism from her earliest collage, but also how she differs. She was almost old enough to have been a Cubist herself, but also old enough to have broken out of its compartments. I could swear that two gray samples have the shape of Picasso's guitars. Sandpaper or a torn doily plays the texturing role of newsprint or the tassel from an armchair for Pablo Picasso. Her textures are kinkier, though, and her chair caning insists on its history as the back of a chair. Stain brings out the grain of the support, as with Georges Braque—only for real and not as a pattern printed on oil cloth.

She never quite fits into half a dozen other compartments as well. The scale of her major work relates to Abstract Expressionism, but off the wall. Her boxes parallel Donald Judd and Carl Andre—like early Stella, in black. For her, though, the furniture is real. Collage, too, depends on found object. Her finds also anticipate Hesse's Post-Minimalism and the overflow of trashy installations today.

Her collage breaks out out of its compartments in space as well. A shovel shares a composition with tin ceiling tile. One might be staring upward while clearing the floor and clinging for dear life to the wall. In truth, her major work looms larger—maybe even too solemn and too large. Collage, though, brings out the humor and the chaos. One could glimpse the alternatives in her retrospective, but the path from off-white through messy furnishings to big black boxes helps to situate them all.

Collage shows Nevelson at work in that slippery space between domesticity and Surrealism. They appear in the coarseness of sandpaper or the black lace of a doily. They appear in the household furniture and its destruction. They speak again to her age, born well before Surrealism in 1899, and to her continued presence until her death in 1988. If there is a definitive feminist version of Nevelson, it is there as well. When she adds a broom and dustpan, she is just sweeping up.

"The Sculpture of Louise Nevelson: Constructing a Legend" ran at the Jewish Museum through September 16, 2007. Her collage ran at Pace in Chelsea through February 28, 2015. A related review looks at Nevelson drawings.