The Entropy and the Ecstasy

John Haberin New York City

Ed Atkins and Al Taylor

Total Disbelief: In Practice 2020

They say that clothes make the man, but they may not be able to keep the universe from eating into him, burying him, and reducing him to dust. Not even two long racks of men's suits can, each two tiers high, for Ed Atkins.

Like a dust-brown car parked in an alley of Long Island City, they are on their way to a final reckoning with entropy—or what the artists at SculptureCenter reckon as "Total Disbelief." And speaking of the cheap and the used, New Yorkers of a certain age may have a habit of looking down. Maybe they are less likely to be on their cell phone. Maybe they are old enough to remember the days before the nation's first pooper scooper law. Or maybe they just know how much is out there on the street. Either way, they have nothing on Al Taylor at the Morgan Library.

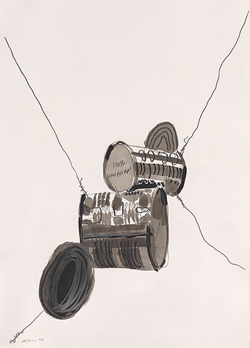

As an assistant to Robert Rauschenberg, Taylor learned from art's greatest scavenger. Where Rauschenberg turned a stuffed goat and an automobile tire into art, he scavenged bicycle tires. He could also claim a direct line to Marcel Duchamp, whose first found bicycle wheel had, fittingly, long since ended up in the trash. He made sculpture from tin cans, too, and collage from coffee ads, much as Jasper Johns had cast a Savarin can. (Taylor preferred Maxwell House.) But then for him looking down brought pleasures of its own.

Old food and feathers

Dowdy clothes would be stifling enough anyway, even were they not wrapped in dry cleaning sacks that seem unlikely to preserve them. Ed Atkins means his entire show as a tribute to entropy—the passage to disorder so beloved of Robert Smithson and Andrea Zittel. It can, at a given moment, become comic, tragic, exhilarating, or stifling, much like a video by Arthur Jafa in that space three years before, but it is never less than encyclopedic. Nor is it exclusively male. It may seem that way from the show's title, "I Like Spit Now." Bear with it though for a less adolescent encounter with the entropy and the ecstasy.

The clothes occupy the center of Old Food, and food seems less than a bulwark against entropy, too. It oozes discomfortingly in and out of shape on several monitors, while a man weeps and landscapes look only momentarily idyllic. Text laser etched in wood brings out each panel's imperfections. The unsigned quotes, by seemingly everyone from Antonin Artaud to Isaac Newton, are not reassuring—most especially when referring to Atkins in the third person. Still, hands at a keyboard may greet you on a monitor on the way in, and a gentle piano piece by Jürg Frey fills the air. And then the camera draws back, and the player piano sits beside an impossibly focused cylinder of light, entering a window and pooling on the floor.

Refuse, er, sandwiches Old Food over the gallery's full three floors, and the gallery suggests starting at the top. Atkins means the two works as distinct, but they overlap in imagery as well as themes. Of course, old food is not necessarily good food (more in fact like refuse), and the bottom floor has a working kitchen. I dared not ask for whom a woman was cooking. Refuse also has still more text, more gentle music, and even momentarily a grander piano. It tumbles down upstairs through the largest video of all, but its very crashing may come to feel redeeming.

The video takes advantage of its enormous height. Feathers fill the air, ever so delicately, like cotton for John Dowell, but then come used tires, an entire piano, and heavy branches. I would love to hear the sound of their crashing. A storm breaks out, the heavy rain broken by white screens for lightning, and then more luminous droplets gather. Atkins might almost have found peace, like a veritable parody of Bill Viola on video standing in the rain, at least until a second projection on the bottom floor, where broader remains crash and gather. Naturally they belong to a kitchen.

So does wood from kitchen cabinets covering an adjacent wall. Back upstairs, white pads to either side of the large projection act as counterparts to the panels below. They function as sound dampeners, so that not even thunder and lightning can come as a slap in the face. Some, though, like Hollis Sigler have knitted flowers out of old-fashioned samplers. Others bear something more enigmatic and less reassuring, more text. It comes knitted in white on white, some of it well above eye level, so that you may never take it all in.

It, too, ranges widely in unsigned sources, from spare notes to memories of a father, but each one amounts to a list of what has been inherited or lost. One inventory weighs in at tons of spices, perhaps the historic trade behind old food. Perhaps, too, each reference and each appropriation has a subtext in a white, gendered imperial history. Still, raw hands struggle against pain in gouache on paper, from a British artist who more often sticks to male bodies—much as everything else here struggles for life. The videos contain random variations in their detail, for a kind of computer-assisted entropy. You can only smile, though, as every last piece crashes down into the light.

I have my doubts

On a cold winter's day, you might hurry past at least one work in "Total Disbelief" without so much as a glance. Parked just outside, an old-model Chevy stands out only in its boxy lack of fashion and a heavy patina of dust and rust. Did Devin Kenny and Andrea Solstad abandon it years ago, when the alley itself seemed all but lost to time? Does it comment on its fancier neighbors today, or does it question any and all truths about life and art? Does the entire show—the latest in SculptureCenter's "In Practice" series for emerging artists? I have my doubts.

I have more confidence in the art. For all some dubious narratives, almost all shares a tactile reality. I would not have recognized bronze in the pebbled courtyard, just past the concurrent exhibition of Rafael Domenech, as bell strikers or wondered if they can give artists a voice, but K. R. M. Mooney has made them of a piece with nearby buckets waiting for rain, the abandonment of the Chevrolet Monte Carlo, and the building's industrial past. I would not have identified ceramics by the head of the stairs as her father's limbs or "my sister's tits," but Emilie Louise Gossiaux lends their cross sections the rawness of flesh and bone. The rest unfolds in the brute presence of the basement tunnels, where the artists do their best to keep up. So what if they cannot sustain their own desires for certainty?

Things can get awfully silly, like a snowman of sand-covered pots by Hadi Fallahpisheh. They can grow dubious, like his claims for a "sexually suggestive" reclining figure. They can become obscure, like references to a math problem in standing cylinders from sidony o'neal. (Quick, how do you use their volumes to pour a specified amount of water, and why does this matter to the art?) They can indulge in the private and personal, like photos of her grandmother's garden by Laurie Kang, amid a winding path of steel studs and tubs set out for the filthiest of foot baths. Still, one is creepier than the next, and Fallahpisheh's figure on the floor sure looks homeless.

Some thrive on certainty, the more absurd the better. Mariana Silva uses set theory to locate "geo-history" at the intersection of "diachronic time" and art—on her way to "inventing the Louvre." Ficus Interfaith looks to art's history, too, to lend a touch of wealth to the brick tunnels in walnut and terrazzo. Andrew Cannon models his black fireplace after one that Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney commissioned for her studio in 1918. Who would have known that its white plaster flames once engulfed the chimney? Somehow, though, they never consumed the future Whitney Museum and American modern art.

The show's gender and ethnic diversity is mostly implicit, as it will be next year with the voices of "In Practice" for 2021, like supposed stereotypes of the Middle East in that snowman. (Um, maybe.) Still, Qais Assali and Jesse Chun chart the immigrant experience, like Daniel Shieh—and call its very poignancy in question. Assali goes about his business in his studio, while the soundtrack alternates between his insecurities and "God bless America." (A Palestinian, he sought residency by posing as an Iranian living in Afghanistan.) Chun masters English by working her way through self-help books and government regulations, finally granting herself a diploma from a long-gone school founded by Henry Ford.

Disbelief remains, if only on video. Who are the masked figures hunting something in the woods—or the hands on at the wheel of a car? Andrew Norman Wilson veers between a private confession, Captain Beefheart, and Donna Summer, all while zooming and cutting his way through an imagined city. Jordan Strafer takes a blond woman through Congressional hearings, like Hillary Clinton, and taunts of "are you a girl?" If the theme still seems forced, I may strain for a narrative myself in reviews like this one. It just need not require total disbelief.

Looking down

Al Taylor found himself studying puddles and stains on the sidewalk. They must have made him feel like a child again, stirring oily puddles with a stick to nurture the taffeta patterns. They must have reminded him, too, of the spills and stains in his art. He took to one source of stains in particular, dog piss. It had him assigning identities to the stains, with pretend dog names. Like dogs and works of art, he must have felt, no two stains are alike.

He was not a natural-born scavenger, at least as an artist. He started as a painter, with not poured paint but geometric abstraction. Some of his first drawings at the Morgan, from the early 1980s, arrange brushstrokes into a cryptic alphabet on a near grid of bright colors. He could make just red, yellow, and blue look like a rainbow. Even with The Big Spill, in 1988, he tempered ink with baking soda for greater control. Still, he was adopting more provocative materials, such as toner and correction fluid, and loosening up.

Not that his move to New York in 1970 made the difference, after childhood and a BFA in Kansas. Taylor credits a trip to Africa in 1980, when he saw how people reused household materials. Not for him an Africa of black power or primitivism, but rather one of sharing and making do. It encouraged him to bring together slats and folds in his newly chosen medium, sculpture, although he continued to pursue his painterly touch in private, leaving thousands of notebook pages and single sheets. They testify to his street-corner observations in Paris, New York, and Hawaii along with his imagination. Once again, no two places are alike.

He is not just looking down, though. He thinks of his work as hanging in space, even the puddles, much as his sculpture can hang from wires. Works on paper give equal attention to the objects, the wires, and their shadows. He values them for their own sake, rather than for their strict associations as with Robert Rauschenberg, their reflection on an artist's studio as with Jasper Johns, or their refusal of art as with Dada. Still, he means digging into the dirt as a challenge. As a title from 1995 has it, What Are You Looking at?

He is not just looking down, though. He thinks of his work as hanging in space, even the puddles, much as his sculpture can hang from wires. Works on paper give equal attention to the objects, the wires, and their shadows. He values them for their own sake, rather than for their strict associations as with Robert Rauschenberg, their reflection on an artist's studio as with Jasper Johns, or their refusal of art as with Dada. Still, he means digging into the dirt as a challenge. As a title from 1995 has it, What Are You Looking at?

Child's play mixes with lyricism, for an artist too often long on charm. Still, it is adult child's play. He calls one dog Peabody, after a highly intelligent cartoon dog of his childhood, but with that pun on pee. He devises pet stain removal devices, "bondage" for a duck, and an elaborate leash for a rat. He incorporates the shape of pest control strips into much of his last art. He died of lung cancer in 1999, at age fifty-one, from one too many adult vices.

At his best, his sense of humor manages to be both shocking and endearing, and it infuses his art. At his best, too, the loose flow of ink plays off against a sculptor's instinct for construction. A title pays tribute to the early Soviet art of V. Tatlin and Kazimir Malevich, who could make his spare shapes appear to soar overhead even when right in front of your eyes. Come to think of it, Tatlin's Monument for the Third International could almost be another of those pretend devices. Taylor's towers, too, loop the loop as they ascend. He kept his eyes on the sidewalk and his creations in the air.

Ed Atkins ran at Gavin Brown through December 21, 2019. "Total Disbelief" ran at SculptureCenter through March 23, 2020, Al Taylor at The Morgan Library through September 13 and at David Zwirner through April 18.