Habits of Disbelief

John Haberin New York City

But modern portraits by English painters, what of them? Surely they are like the people they pretend to represent.

Quite so. They are so like them that a hundred years from now no one will believe in them.

— Oscar Wilde

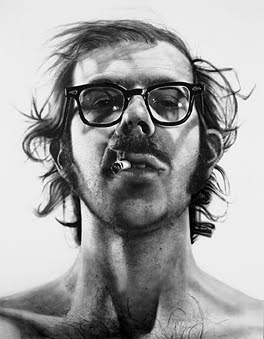

Chuck Close

Chuck Close is deceptive. I do not mean just how well his portraits deceive the eye. I mean his range of influences and his increasingly wild, painterly style. How easily they disguise what interests me most, his fixity of purpose. Close dares to stake his humanity on his art, his art on mechanical reproduction, and its reproducibility on his fallible humanity.

Getting close

He starts with large photos, all head shots, of his friends and himself. They almost all face dead front, but they hardly trouble to make eye contact. I imagine them unsure whether to pose as friends, icons, or just themselves. They never quite pull any of these off, either. True friends, much less media celebrities, might comb their hair from time to time.

Guided solely by his eye, Close transfers their images to enormous canvases. Over three decades now, he has created an entire personal world, almost lifelike and just as weirdly rigid. It is a small world, and he never varies from it. He might use the same photograph more than once, even decades apart. Only Close himself is permitted to age.

It is also the art world. He identifies his friends solely by first name. For someone like me, who never travels in the right crowd, part of their strangeness amounts my having to guess just who they are. Perhaps Close intends my discomfort, for his realism never means to rest on familiar terms. It comes larger than life.

Close has ties to all sorts of trends, if mostly from the 1970s, but going back to his own role in the birth of Soho. One thinks of photorealism, but just for starters. From abstraction he takes the gigantic scale and an art at least one step away from seeing. Josef Albers supplies the grid, Andy Warhol his elevation of the media icon and celebrity portraiture, Wayne Thiebaud his coolness. But Close is his own movement, one that reflects on all of these.

Close elevates the "age of mechanical reproduction" as enthusiastically as any postmodern artist. If all modern art came as a response to early photography, no one else worries so much and so long about how to respond. If human identity begins with what Jacques Lacan calls a mirror stage, no one has spent longer in front of the mirror. If originality and humanity are illusions created by superhuman forces, no one else puts the illusion through quite so many paces.

Despite the size of his works, his show at the Museum of Modern Art stretches to ninety of them, just in case one has somehow missed his fixity of purpose. It makes good sense that he shares the Modern with a retrospective of Fernand Léger and his mechanical humans.

Left to his own devices

Close begins at his most photorealist, in fine brushstrokes of black and white. I always get a kick out of Phil Glass, the composer and another clear link from Close to Minimalism. With his head thrown back, he looks quite charismatic already, though not quite poised for a future in grand opera.

Before long the trickery gets more overt. Close pulls the trick off in color. He first tries watercolors, daring one to catch him in a medium associated with casual sketching. He shows his preliminary drawings in one color, then in combinations of two or three. On the final canvas, too, each stroke will carry a single color. Close—who knows how print makers can endlessly revise a single unfinished or finished plate—has turned painting into a form of printing from "color separations," with himself as the plates.

Soon textures creep in. He constructs the grid on a looser grain, filling dozens of squares with arbitrary strokes or even fingerprints.

The more the hand prints stand for an artist's mark, the more each finished work begs one to forget expression. These marks add painterliness as they heighten the virtuosity. Picasso said once that he had to spend his whole life learning to paint as a child. As if in answer, Close takes up finger painting, and he is a fast learner.

Sadly, Close lost almost all physical mobility about a decade ago. It seemed certain that he would never paint again. If tradition compares recovery from illness to a miracle, it uses the same metaphor for representation. Close's career testifies to disbelief in miracles, but he keeps creating them. He even takes advantage of his physical limitations, to continue his growth toward wilder, sneakier constructions. The grid enlarges to squares nearly an inch high, and strokes may span three or four. I feel the same tension as in John Coplan's bleak photographs of his aging hands.

Sometimes the device pays tribute to a sitter's personal or artistic style. Elizabeth Murray gets a bright carnival of circles and diamonds, wilder even than Murray drawings. Lucas Samaras gets dark tones and a satanic stare instead of his usual psychedelic dislocation, as with Samaras in pastel. Personalities, like last names, may stay hidden, but not their art or his own.

Magic realism

Through all those permutations, Close is up to one thing. His portraits imitate the photograph, hoping to understand it and yet out to trump it. He keeps trying harder and harder to fail, and he succeeds. He sticks to the formal, modernist vocabulary with which he began. Like a printer or a factory, he reproduces it endlessly. Yet he trusts only to his eye and hand.

Close has set the bar higher even for photographers, such as Thomas Struth. Yet his very first black-and-white paintings were hardly all that precise. Paradoxically, he depends on the photograph for their handmade look. The sketchiness of an ear, say, coincides with the blurring due to a narrow depth of field.

Close is fascinated by how reality at a third remove can seem so real. He is in love with a photograph's lack of authenticity and yet determined to control it. Year after year he repeats his formal gesture, like Freud's child tossing a ball over and over to confront a sense of loss. He has lost the comfort of art's humanity and his own claim to genius, and again and again he replaces it with his outsize talent.

Is this narrowness boring? Well, yes. I never think of Close when I name artists I like the most, and I guess I never fully accept him. Numbed by almost a hundred of his works, I may never have gone through so large a retrospective so fast. Twice.

The narrowness, though, is precisely what I like about him. It puts his subject's humanity and artistic genius through the wringer, and they emerge on the other side of a work of art. Remember those magazine columns of "mathematical diversions"? In a parody, Veronica Geng wrote that "the trick is ridiculously easy to understand once it's understood." Apparently not for Close. He is the magician who tired his audience long ago but can never get over his own amazement.

Oscar Wilde wrote his dialogue exactly 100 years ago, and he might have been more at home with someone like John Singer Sargent in artist portraits. He could, however, have been with me at the Modern. He could have been talking about the stunning, insistent, frustrating art of Chuck Close.

The genius and the charlatan

As echoes of Wilde suggests, Close repeats an old message of modernity: art's magic is an illusion, especially when it will never let go. Humanity is one thing left for certain, like the speed of light or Picasso's Blue Period. And yet the people one knows best remain strangers. Somehow or other, the lonely artistic genius still towers above it all, but modern art remains barely accessible.

Face it: everyone knows the genius of Picasso or Einstein. Anyone can see it right there, in the ads for Apple computers. Richard Feynman was a genius, too. It says so, in the title of his best-selling biography. Do not even mention Stephen Hawking.

But what about Georges Braque or Werner Heisenberg? What about the co-inventors with Feynman of quantum electrodynamics or others who have charted black holes? What about an alternative history of Modernism, as with Mark van Yetter, filled with collective movements such as Dada and Blue Rider?

Starting with Postmodernism, artists and critics have asked exactly that. And that has a lot to do with Close's uncertain standing now.

The questioning turned into a demand by 1968, almost when Close began. Students then ran to the barricades bearing Sartre, but they rushed home to read Derrida and Foucault. They came with an existential crisis, and they left with inner visions trapped in the hands of therapy and home design.

Meanwhile, the lone creator got absorbed into Hollywood myths of the tormented genius, Vincent van Gogh with one ear and an inner eye. Close's habits of disbelief could almost toy with Hollywood in his own way. The painter cannot, however, stop making himself and his friends larger than life.

Beyond the barricades

In the myths about genius, a creative individual stands for more than a person, like another icon on the desktop of virtual reality. But it is a myth, and one can sketch its contours precisely.

Those at the forefront of humanity fight the establishment, or so the sketch goes. They create alone, and they suffer the world's neglect. Original and alienated, witty and wise, authoritative and loving—there they stand, to remind ordinary men and women of what they are.

Like Einstein invoking God, they offer conventional wisdom, remote from their particular discovery. Like Picasso or Hawking, they have an interesting social life—a little sex, arrogance, perhaps a disability. They definitely make themselves visible in America.

Close helps penetrate those myths, but only because he needs them so desperately. He has become like the Apple ad, snatching geniuses who will never endorse a computer, long after the art world has turned appropriated images inside out. Meanwhile art's magic has moved on to video, interactivity, and digital manipulation, as for Bill Viola, only to raise again the difference between the magician and the charlatan.

Close has the stubborn custom on belief, along with the insight to disbelieve again the next day. Those old-fashioned ways of approaching his art explain why not everyone finds him still provocative. He is the controlling artist, decades after installation art stopped trying to control it all. And yet you, too, will want to go through his show twice.

A postscript: problem child

"I've always thought that problem-solving is highly overrated and that problem creation is far more interesting." That is Chuck Close in, as far as I can tell, the sole issue of a webzine called Artzar. I first came upon it in March 2005, perhaps three years since its publication and almost seven years since the foregoing review.

I found it a hard quote to resist. It has something of art's refusal—or perhaps inability—to settle anything and something of the avant-garde's spirit of troublemaking. It gets at the deductive logic of Close's entire generation, including Minimalism and abstraction. And of course it points to something more specific still, in Close's perpetual complication of photorealism and of his own momentary solutions to portraiture.

The entire 2002 interview, in fact, has a nice way of letting Close reveal himself. Rather than pressing him on his personal history and his intentions or, conversely, giving him the hiding place of a lecture on other artists, John Clay invites him to speak about what matters in art generally. As generalities must, that results in some interesting but rather dubious claims. Or at least they sound dubious the more one thinks about them—until one thinks about them as about Close's art.

Vermeer and the Delft School at the Met, he says, shows that Jan Vermeer cared about light but not about things. The symbols and circumstances surrounding the couple in Jan van Eyck's double portrait distract from what really matters. In art, especially modern art, one should look for the process of its making.

Each claim has its temptations, including the temptation to miss so much of what obsessed other artists, what the works actually show, and what allows them to participate in a viewer's experience. Each, too, suggests the process, the searching, the skepticism, and the delight in vision that go into Close's deceptively polished paintings.

Besides, he also reminds one of the limits of criticism. It can get overt (and deserved): "Hilton Kramer hated the work, and if he had loved it I would have wanted to commit suicide." However, even critics truly in love with recent art, ideas, and words have their place and limits, too.

The exhibition of Chuck Close ran through May 26, 1998, at The Museum of Modern Art. The Artzar interview appears to have taken place in 2002.