Rosemary's Preschool

John Haberin New York City

Regarding Warhol: Sixty Artists

Robert Hughes once called Jeff Koons the baby to Andy Warhol's Rosemary. With "Regarding Warhol," the Met has the entire preschool.

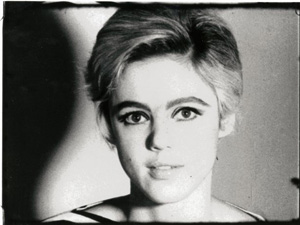

It is not a pretty sight. Like most urban classrooms, it is sadly overcrowded—as the show's subtitle explains, "Sixty Artists, Fifty Years." Add Elvis and Marilyn, who can hardly get enough attention, and Warhol himself, who contributes forty-five works to a good hundred others. Like most public schools, too, it is sadly focused on test results, with a selection seemingly designed by sales rankings. It is sadly in need of repair as well, with hardly a thought for Warhol's influence on the present. It all but ends where it began, with Warhol's Cow Wallpaper, silvery Mylar balloons, and of course the museum gift shop.

Some kids, like Koons, are way too coddled, well past their fifteen minutes of fame. All get to run where they like, with hardly a thought for chronology. Way too many seem to have stopped by simply because they were in the neighborhood, Warhol or no Warhol. Several predate their supposed teacher, and more than one despised him. It makes for a dispiriting and thoroughly misleading exhibition, but you know what? It also makes for a fine retrospective of a remarkable artist, and it should have a lasting impact regarding Warhol.

This Warhol means business

Not many young artists get to milk their day job for an exhibition, but Andy Warhol did. He was designing window displays on Fifth Avenue, in 1961, when he included his own canvases—then still hand painted and still never seen before in public. "Regarding Warhol" includes one, Before and After, based on an actual ad for a nose job. How you react to the story may define how you look at Pop Art and Andy Warhol. Most, no doubt, will be glad, at least for his sake, that he could get past the need for a day job to devote himself to art. Others will see instead the casual mix of art and commerce that employed a young Warhol as illustrator and has made his influence so problematic ever since.

A few, though, may wish that they had been there—or wonder if they were. I was a little boy when my mother dragged me along each Saturday to department stores, and who knows? Could I have seen it? The Met would surely be among the curious. Regarding Warhol, it sees five themes, and all would have felt quite at home at Bonwit Teller. They show him borrowing from tabloid photography, wrapped up in celebrity and consumption, dealing with sex as one more excuse to dress up (or down), and taking art outside the studio and into commerce.

The themes are a mess, and shoehorning them into an oversized show is messier still. A cow by Gerhard Richter and wallpaper of a lynching by Robert Gober come a good dozen rooms before Cow Wallpaper. Empire, an eight-hour shot of the Empire State Building, comes a couple of rooms before Warhol's Screen Tests—and well before a glimpse at reality TV. Sigmar Polke contributes the first Ben-day dots (inspired, of course, not by Warhol but by Roy Lichtenstein), not yet as a silkscreen but by hand, and Alex Katz the first celebrity portrait. Richter worked ahead of Warhol, too, as did Nam June Paik with TV, but never mind: this show hedges again and again on whether it displays influence or a dialogue.

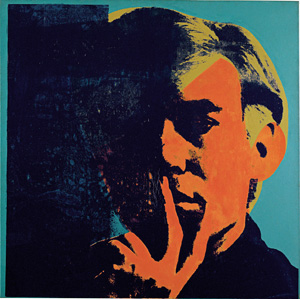

The themes also leave a good deal out. They omit Warhol the formalist or anti-formalist, other than a 1967 double self-portrait in contrasting neon hues—or the grid of Coca-Cola. They play down Warhol the collaborator, with all the messy issues raised by the Factory. No wonder the show has just two Warhol Screen Tests, both digitized on small monitors. The themes also dismiss the artist who made it hard to say what can be art, when he painted Brillo boxes in wood but, Arthur C. Danto insists, indistinguishable from the originals. The Warhol at the Met means business, and I mean business.

What explains this version of the artist? If nothing else, it is a sign of the times. Mark Rosenthal organized the show with the Met's Marla Prather, Ian Alteveer, and Rebecca Lowery. They know how often critics and artists today address economics and gender, rather than formalism and epistemology. They surely know how questions of authenticity have become questions of identity, not a questioning of knowledge and of art. As they proceed from the first coarse quotations of advertising to dollar signs and those Mylar balloons, the show finds, if not Warhol, today's museums.

Another answer, though, is lack of imagination and just plain pandering—and can we stop blaming the curators for their bad taste, when they are really, and sadly, just pandering to economics? Warhol was not the only Pop artist, any more than Pablo Picasso was the only Cubist or Henri Matisse his only rival, but their names sure sell. That is why the Guggenheim is opening "Picasso Black and White" and the Met Matisse working in series, as if they had ever really gone away. It is why Robert Hughes often turned to Warhol to express his dismay at contemporary art, period, while readers ogled the debate as if reading a tabloid. It is why the Met rounds up the usual suspects, whether Warhol influenced them or not. As Jerry Saltz notes, they read suspiciously like the roster at Gagosian.

Exploiting Warhol

The very idea of Warhol's influence has become a cliché—which artists, in turn, can happily quote. The curators may be updating the idea of the artist, but they are already behind the times. The Young British Artists were about not shock and appropriation but appropriating shock and appropriating appropriation, and that was only the 1990s. Critics have since turned against art stars and flashy installations, but that was last year's news, and they have panned this exhibition as well. It has almost no one under fifty, and Ryan Trecartin here owes more to rock 'n' roll than to Pop Art. So for that matter does Karen Kilimnik, born in 1955, who also just had a show in Chelsea with Kim Gordon of Sonic Youth.

A visit to Chelsea and the Lower East Side this fall would have turned up any number of younger and much hyped revelers in pop culture, like Eric Yahnker with his celebrity politicians and pop stars. Richard Philips uses video and painting for a fashion shoot with Lindsay Lohan at, yes, Gagosian. I could live without them all, ever, and "Regarding Warhol" shows real wisdom in not going there. Still, it suggests why a dialogue with Warhol alone is so hard to pull off. He most certainly did not invent Pop Art, an honor that belongs to Robert Rauschenberg and Jasper Johns, and he had plenty of company in exploiting it.

Polke sure exploited it, and he gets the most space after Warhol and Koons. Ed Ruscha did, all the way on the West Coast, but he turns up only because Burning Gas Station has something to do with cars. Robert Mapplethorpe did not care for pop culture, although he documented (and experienced) AIDS at first hand—and not at all thanks to Andy Warhol. Chuck Close parallels Pop Art in his photorealism, but he appears only because his portrait of Philip Glass has such iconic status. Never mind that Glass was probably still driving a taxi when Close painted it. Cindy Sherman has dabbled in stardom, posing as Marilyn Monroe, but only as a detour and in maybe her worst series.

Other influences look plausible enough but slip away the closer one examines them. Catherine Opie photographs a neck tattooed Dyke, but Warhol had the gift of making gay identity normal and normalcy a pose, and anyway Gilbert and George were the ones to incorporate the word Queer into a work of art. Polly Apfelbaum has a floral carpet, but as part of an often overlooked woman artist's discovery of decorative arts and craft. Bruce Nauman has neon lights for EAT within DEATH, but not even Warhol has the patent on mortality. A pile of candy by Félix González-Torres takes on new relevance, amid Warhol's images of desire and death, but largely because the museum covers its butt with a warning that swallowing can cause choking.

Other influences look plausible enough but slip away the closer one examines them. Catherine Opie photographs a neck tattooed Dyke, but Warhol had the gift of making gay identity normal and normalcy a pose, and anyway Gilbert and George were the ones to incorporate the word Queer into a work of art. Polly Apfelbaum has a floral carpet, but as part of an often overlooked woman artist's discovery of decorative arts and craft. Bruce Nauman has neon lights for EAT within DEATH, but not even Warhol has the patent on mortality. A pile of candy by Félix González-Torres takes on new relevance, amid Warhol's images of desire and death, but largely because the museum covers its butt with a warning that swallowing can cause choking.

For all that, "Regarding Warhol" does its job well indeed regarding Warhol. Sure, like many a so-so exhibition, it has its share of good artists and good art. Playing it safe has its virtues. The Met, though, also lets one look with those artists, at Warhol. It surveys his career, on a manageable scale. One can also see how badly he fell off in the 1970s, as with the dollar signs and Mao, and give thanks for how little late Warhol the exhibition includes.

One can learn about him, as from any good retrospective. Did you know that the Mylar balloons accompanied Cow Wallpaper back at Leo Castelli in 1966—or did you know what you may have seen at Bonwit Teller? Had you forgotten that the magazine quotes began with an ad for Dr. Scholl's, even more roughly drawn in casein and wax crayon? Are you surprised that early silkscreens included home runs by Roger Maris, elevating the grid to film cels while reducing an all-American display of power to mere repetition? Just as much, too, one can learn a great deal from the pairings that do not add up, and one can ask why, if he did not invent Pop Art or avant-garde film along with Jonas Mekas, people really do care so much. One can ask what made Warhol at once so unique, anonymous, and influential.

Best regards

The very nature of art was in one of its many crises, and Warhol helped immerse art in life. Yet (as Joseph Masheck observes) he never did make what Danto wanted to call indiscernibles. Gober did, with a plaster and latex bag of cat litter, but no one today would confuse the Brillo boxes, parts so strangely bare of paint, for the real thing. Jeff Koons and Damien Hirst did not, but in a different way than Warhol—for Jeff Koons gave actual vacuum cleaners a museum display case and museum lighting, while Hirst's medicine cabinet holds actual drug boxes. Hans Haacke did not, with supersize Marlboros that lend his attack on tobacco country some desperately needed humor. If Warhol influenced them, it is because he taught them that a critique of the "originality of the avant-garde" involves making changes.

Warhol's prints include Birmingham Race Riots, much as Robert Indiana singles out states with violence against civil-rights workers, but Warhol stops short of sending a message. Where Polke paints a labor leader, Warhol paints donors. Where Alfredo Jaar rips off magazine covers for the Bhopal disaster, Vija Celmins for LA riots, and Barbara Kruger for a shock jock, he prefers the ads. Where a Louise Lawler photograph treats Jackson Pollock as room décor for the wealthy, he gets to make his own drip paintings, in piss. Even when it comes to gay identity, Deborah Kaas or Nan Goldin is the one cross-dressing, and David Hockney is the one ogling. The one time that Warhol lets his sexual appetites show, in a portrait of Jean-Michel Basquiat, it gets clinical—with not ogling but x-rays.

In other words, Warhol knew when to remain neutral, and neutral need not mean bland or tame. At his best, detachment itself carries the cutting edge of emotion and its own "sinister Pop." Not for him Koons's cute little angel and boy with a pig, called (in case you failed to get the point) Ushering in Banality. Not for him Keith Haring's cuddly Elvis—not when he can double Elvis, as a gunfighter, both packing a pistol and playing a role. Nauman's nearly hour-long video of a long night in an office, empty but for a cat, packs its own discomforts. Set next to Empire, though, or to William Klein in Broadway by Night,, it could be home sweet home.

Warhol's neutrality points directly to the violence in American culture, quite as much as Llyn Foulkes in LA, and other artists understood. I could forgive Basquiat's black painted skull or Katz's portrait of Ted Berrigan for that alone. The curators suggest that Warhol could hardly avoid thinking of death, after the AIDS crisis and, earlier, an attempt on his life in 1968—the subject of the film I Shot Andy Warhol and, implicitly, a skull in the Jack Shear drawing collection. Yet the electric chair of Orange Disaster came well before that, in 1963, not so very long before Marilyn and Jackie, women haunted by early deaths. The very first silkscreens depict America's most wanted, as objects of both desire and fear. Once again, Polke comes out ahead of the game, with the ghostly watchtower of a concentration camp against a dark red.

Too often, "Regarding Warhol" drops its regard and turns away. The jarring leaps back and forth in time should get one thinking—and I still wonder whether Bonwit's customers would have felt in on the joke. The easy cheer of Koons's gilded Michael Jackson, video games for Cady Noland, the Loud family on television, another cowboy from a smirking Richard Prince, a slick portrait from Richard Avedon, or anything at all from Takashi Murakami in Japanese art will not. Still, the leaps and the cheating have an added benefit. They cannot convince me that Warhol started it all. They can, though, make him an essential part of his time.

By the end, I was impatient and exhausted, tired of the preschool and tired of more of the same. The Met even enlarges its galleries to fit it all in, so that one exits not where one started, just outside the twentieth-century wing, but within it. There one first stumbles upon Lichtenstein and James Rosenquist—a reminder that they, too, were at work back then, mostly without regarding Warhol. And there one exits past some heroic Abstract Expressionism. For a second, it may look like more of Warhol. At least he sends his regards.

"Regarding Warhol: Sixty Artists, Fifty Years" ran at The Metropolitan Museum of Art through December 31, 2012. Related reviews look at late Warhol, his brush with death, and the "Screen Tests."