Abstraction as Recitation

John Haberin New York City

Jennifer Bartlett: Recitative and a Retrospective

In music a recitative lies between speaking and singing. If that sounds like a good metaphor for art, Jennifer Bartlett in 2011 takes Recitative as a title for her most sweeping painting in quite some time. It also promises safe harbor in the past.

Two years later, her past takes on a stranger shape, with a retrospective in Philadelphia. The harbor is still there, right by the ocean, but the sense of safety is gone. It asks one to see Bartlett as a painter of light, sea, and sky, but also as a text artist. Yet is has gaps of its own. A separate review spends more time with Rhapsody, the work that set her themes for years to come. After all this time, she is still chronicling the languages of art.

Scaling abstraction

A recitative allows an opera to be "sung through," without bringing the action or dialogue to a halt for an aria. It allows moments of comedy amid grander displays of emotion. It allows characters to address one another or the audience, rather than heaven and earth. Yet it also displays the tension between music and drama that led to Mozart's rapid-fire overlapping voices and, ultimately, Wagner's dream of a total work of art. In a sense, Modernism is all about the fulfillment and utter collapse of that dream. And Jennifer Bartlett's best work is all about another day, savoring the waking fragments of the dream, and wondering what comes next.

She makes entering a room an immersion in just that moment. Her best-known work, from 1976, covers the walls with a grid of nearly a thousand identical plates. Rhapsody builds from the search for a common language, and it cherishes the languages of art it knows. Yet its grid within grids spins out into new elements, most notably a house as a child might imagine it, and then into black. As one looks from left to right, the possibility of seeing painting as a time line becomes impossible. Back when formalism seemed to have defined painting once and for all and when Minimalism put the very possibility of painting in doubt, Bartlett managed to take on both claims—and then some.

Rhapsody takes the measure of art—or maybe three measures. It works from the scale of a gallery, the scale of the small plates that lined its walls, and the scale of a brush mark, which in effect defined the grid within a plate. When it filled MoMA's atrium in 2006, it supplied another missing element as well, a bridge between the museum's history and contemporary art. More recently, Bartlett has painted a garden, as if in tribute no longer to Minimalism, but to Joan Mitchell or late Monet, and rendered her hospital stay in pastels. Or maybe the successful artist has simply moved out of the house that, in Rhapsody, vies with abstraction. Now, with Recitative in 2011, she tempts one again with reductive logic.

Recitative keeps the scales but throws away the house. It again covers three walls with enamel on baked steel, and the gallery even uses its fourth wall for a display case of her past catalogs. This, it seems to say, is the definitive Jennifer Bartlett. Now, almost by definition, the definitive Jennifer Bartlett is never definitive. Along with other abstract artists, she asks what painting in the present can still add. And she asks whether painting today can be not just tasteful or formulaic but ambiguous or even fun. The answer is by no means clear, but maybe that is the point.

In Rhapsody, Minimalism and color-field painting are implicit in the form. Now they are explicit in quotes from others as well, like what another show calls "Geometric Days," and these others were finding their own ways past a minimal logic. The first wall ends with the firm curves of late Marden. The second wall opens with the surprise of drip painting, before diagonals out of Frank Stella and crosshatching out of Jasper Johns. The work ends with white plates tilted like the folded paper of Dorothea Rockburne. The grid that allowed so much virtuosity has broken down entirely, but it offers a ground for something more—in spare, fluid black curves.

Recitative returns Bartlett to her roots, and that does not mean a garden. Its title may well suggest a musician running scales or a schoolchild doing recitation. And it is a virtuoso performance, but completely abstract and within the styles around her when she began. Naturally she quotes herself, starting with the medium of enamel on baked steel, before outracing her own ambitions. The plates have first the small grids and then single fields of color. They again settle at last into black and white.

A parallel universe

It is not easy to grant Bartlett a retrospective. She has, after all, staged more than one of her own in just a single work. Her breakthrough in Rhapsody spanned nearly a thousand plates and almost as many languages of art. Today's career-driven scene would probably call it a midcareer retrospective.  She covered the walls with her next largest work, Recitative, only to leave much of her own elements behind. It dances around the earlier hints of a common language, in something like a child's rendering of nature, in favor of abstraction—only to spin progressively away from the grid and out of control.

She covered the walls with her next largest work, Recitative, only to leave much of her own elements behind. It dances around the earlier hints of a common language, in something like a child's rendering of nature, in favor of abstraction—only to spin progressively away from the grid and out of control.

Strictly speaking, neither of those retrospectives was yet hers. The first came all but out of nowhere and everywhere at age thirty-five. The latter takes pains to quote practically everyone but herself. Maybe that is why her actual retrospective in 2013 skips New York City. Maybe, too, that is why it also omits not just those two major works, but pretty much her entire key decade or so, beginning in 1976. And maybe that is why she calls the exhibition "History of the Universe" rather than her own. Something sweeping is at stake, but in what parallel universe?

Organized by the Parrish Art Museum on eastern Long Island, it seems to belong to a month in the country, but hardly a day at the beach. The largest work, the only one that wraps around a corner, shows the Atlantic Ocean as a dark green driven by the wind. From 1984, it fades more and more from left to right into the white of the tiles or the sky. It also has a smaller portion on the right-hand wall, as if to quit somewhere between peace and exhaustion. A swimming pool from the year before, both in a triptych and again on five canvases, is drained of water and of all but a shadowy life. Two life-size sailboats from 1987, in sculpture paired with canvas, have run aground.

Each is both deliberately schematic and richly observed. The boats, painted white, are hardly more than building blocks, like the rectangle and triangle of a house back in Rhapsody. One can also imagine taking one to sail away. The house itself appears in a painting from 1978, but with the central element ripped out of its expected spot and displaced to the right. It would have no home either at the Soho address of the title, 237 Lafayette. The title insists on its specificity all the same.

Bartlett's color, too, falls between art and nature. She tends to primaries, sometimes in dense scrawls as ground for a larger mass in black or white. Yet she can also identify her subject as Amagansett in the Hamptons, and she devotes a series from the early 1990s to times of day, each with its own light. If one painting also happens to have a couple kissing out of Marc Chagall (or perhaps Alfred Eisenstaedt), fine. Her empty pool's presiding deity, a statue of Cupid, is between art and nature as well. So perhaps are the stains on the bottom of the pool, mixing algae and blood red.

The curator, Klaus Ottmann of the Phillips Collection, opens the show with another series, The Seasons from 1990. Each canvas has the saturated light of afternoon sun, but rain and show pelt across two. Playing cards, dominoes, and a skeleton mark the picture plane in all four. One can imagine long time exposures in dark weather. One can also imagine an artist trapped indoors long after Jackson Pollock has crashed into a tree and the summer crowds have gone. Bartlett calls a windy day No One Is Home, from 2006, and that "no one" may or may not include her.

Back to the garden

Born in 1941, Bartlett grew up near the ocean, in Long Beach, and studied at Mills College and Yale before moving to New York in 1967. The show's one early work, of the earth and Mars from space, certainly looks observed at first hand, although she is more likely to have copied them from a magazine. A photograph would have done just as well, in fact, which may be why she started to look beyond conventions and representation. Most of the show, though, skips ahead to the last decade. It also has her working more with text, in increasingly gnomic inscriptions. "This is the exact spot where those who will live meet those who will die."

The text signals more than a few of the changes in her recent work—toward less complexity, a greater darkness, and a heightened self-reflection. The joyful and seemingly artless sophistication of Rhapsody belongs firmly to the past. Her text does, though, pick up the grid of earlier works, with their hundreds of small cells within dozens of tiles. "Do you remember those stories?" Apparently they are not so easy to forget. Neither, it appears, is the weather.

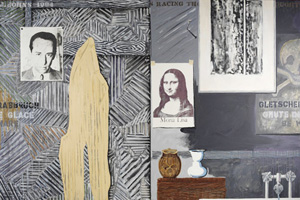

The Seasons has the fullest play between dark and light, nature and art, two and three dimensions, and personal and collective histories. It is an old subject for art, from Nicolas Poussin to Mark Rothko, if not quite as old as the universe. Yet it comes closest to another artist late in life, Jasper Johns, with Johns in gray and his Racing Thoughts from 1983. Even in a disappointing retrospective, Bartlett is taking on the big boys. "Thus we inform ourselves," concludes another text painting, not necessarily ruling out lies. Johns might have said the same about his art as well.

Bartlett breaks the grid almost from the beginning, but not in exactly the same way. Where Rhapsody has nearly a thousand plates, Recitative has fewer than four hundred. It filled a posh Chelsea gallery larger than Paula Cooper's Soho space back in 1976, but its columns vary in height, like a bar chart. Like a chart, too, it could well take abstraction through those lean years when people insisted that painting is dead. The physically open spaces also insist on an open-ended future. Still, the final loose curves have the sense of an ending, as Rhapsody does not, and that ending lies in the past.

Maybe that explains why Rhapsody is exciting, whereas Recitative and her retrospective are just deeply satisfying. They are not giving painting a way to survive, but taking well-earned pleasure in its survival. They are not so much looking around as looking back. Maybe that explains, too, why one can see signs of the 1970s and its New Image painting all over the place right now, as with Michael Hurson and Donald Sultan. Some painting out there is pleasant enough, if derivative, much is both more and less than painting, and much more is just plain boring. Some, though, shares Bartlett's enigma of past reflection and present satisfaction.

I thought of her with the colorful radial geometries on the wall recently from Odili Donald Odita or, less daringly, Yves Oppenheim. Jeremy Gilbert-Rolfe returns to his own practice from decades ago of large canvas, strict grids, asymmetry, and fields of white, but with small brushwork that makes me think of Bartlett's encyclopedia. Many others have embraced her space between abstraction and bare signs of the real. It seems an odd time to complain about a dearth of attention to traditional media, but artists do it constantly. The real question is what they have to add. Perhaps there is nothing new under the sun, but at least the garden in sunshine is more colorful than ever.

Jennifer Bartlett ran at Pace through February 26, 2011, and at the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts through October 13, 2013. Yves Oppenheim ran at Perry Rubenstein through February 12, 2011, and Jeremy Gilbert-Rolfe at Alexander Gray. Odili Donald Odita ran at Jack Shainman through December 23, 2010. Related reviews look at "Rhapsody" when it entered The Museum of Modern Art in 2006 as part of the Edward R. Broida collection and at the pastels in "Hospital."