The Best of the Worst

John Haberin New York City

Shuttered Galleries and Diversity: 2020 in Review

Can there still be the best in an awful year? And would anyone care to remember it?

Well, of course, you might point out. There is always a best, by definition, even in 2020—all the more so, in fact, for a bad year sets the bar so low. Then, too, one can always hope for the best. All right-thinking people say so. As for remembering, that is half the point of singling out the best, as a hope for the future. It may well be the point, too, of the best art.

About you

Which is also the problem, in a year that many would just as soon forget. Many are calling it the worst year of their lives as well, and I feel guilty already singling out its toll on art. You know the litany all too well, and I have covered art after Covid-19 here as well again and again and again. Galleries shuttered, all too many for good. Museums stood empty, with decimated staff and depleted finances. The unthinkable, in museum deaccessions, took place as well, starting at the Brooklyn Museum.

Shows were delayed or canceled—shows that might have launched a new art history or a career. Even shows that had no doors to shutter, in summer sculpture and public art outdoors, shared their fate. Hoped-for substitutes in virtual art fairs and "virtual exhibitions" can never fully deliver. The toll falls on artists, curators, dealers, and just plain anyone who cares about and misses art. It respects neither museum directors nor the more precarious plight of those who work behind the scenes.

I hate to repeat it all for you, but that, too, is the point. This is all about remembering. It is not in praise of stubborn survivors, that old recourse of newspaper columnists in trying times, for not everyone survives. Whoever you are troubling to read this, this is about you. I could simply call us the best of 2020, and I could just as soon stop there. Besides, you know how much I hate ten-best lists, as if criticism at its best were about picking winners rather than sharing insights and discoveries.

Allow me to go further anyway, because the best and the worst are so hard to forget. Just for starters, there are the everyday openings in the face of dismal attendance. There are the premature closings that have reopened, but that you might still have missed. The Met's British wing, newly remodeled, opened in March just in time to see it close. A new home on Essex Street for the International Center of Photography had opened in January, and it dedicates its reopening to shows about New York after Covid-19 and New Yorkers who care for others. MoMA's 2019 expansion came still earlier, but many have not had a chance to catch it even now, and it looks still stronger after further rehangings, in a 2020 "fall reveal" and 2021 "fall reveal."

The Met utterly mismanaged its move in 2016 into what had become the Met Breuer (and then the Frick Madison). It meant to use its lease to permit shutting and renovating its own wing on Fifth Avenue for modern and contemporary art. Instead, the addition helped blow the budget for just that. The museum had to abandon the building years early (a boon to the Frick Collection, otherwise closed for a makeover), but at least, it hoped, it could go out with a bang—a retrospective of Gerhard Richter, curated by a challenging postmodern critic. It had barely enough time for a whimper, for the show lasted barely a week. Still, I want to remember the former Whitney Museum for how well the Met restored it and for nearly five years of shows along the way.

Richter may have had the shortest-lived blockbuster ever—and hardly the most memorable, a mere postscript to the 2002 Richter retrospective at the Museum of Modern Art. A full room for Richter in MoMA's reveal, for his series on German terrorists who died in prison, shows how much its high-concept approach leaves out. Two other blockbusters, though, should make any best list. Donald Judd at MoMA (and with even larger work at his gallery, David Zwirner) shows Minimalism's maximal ambitions. Mexican muralists at the Whitney were more ambitious still. They encompass prewar Modernism, Latin American art, Abstract Expressionism, a political revolution, and the passions behind them all.

Diversity and struggle

Still, this was not the year for blockbusters. I shall remember not the ponderous futurism of Rem Koolhaas at the Guggenheim, but the quietude of Agnes Pelton, a visionary modern artist at the Whitney. One might remember, too, a series by Jacob Lawrence at the Met, The American Struggle. Then again, one might forget about museum exhibitions entirely after all the closures. MoMA's greatest gains lie in its galleries for the permanent collection, including another remarkable series, by Carrie Mae Weems. Its focus on what it had all along makes deaccessions in Brooklyn more shameful still (and I shall tell you more about that in the weeks ahead).

The rest of the best falls largely outside the obvious institutions. It shows art as neither crushed nor surviving, but in a time of struggle. A growing inequality in the galleries could be a parable of the economy under Covid-19 and Donald J. Trump. Chelsea lost ground, even as a new monster space for Hauser & Wirth joined last year's seven-story building for Pace. The Bushwick scene all but vanished, and the Lower East Side had its turnover, even as new clusters settled down within walking distance, and they had their highlights, too—in Chatham Square in Chinatown and just a few blocks of Tribeca. Now if only the first were closer to the subway.

The rest of the best falls largely outside the obvious institutions. It shows art as neither crushed nor surviving, but in a time of struggle. A growing inequality in the galleries could be a parable of the economy under Covid-19 and Donald J. Trump. Chelsea lost ground, even as a new monster space for Hauser & Wirth joined last year's seven-story building for Pace. The Bushwick scene all but vanished, and the Lower East Side had its turnover, even as new clusters settled down within walking distance, and they had their highlights, too—in Chatham Square in Chinatown and just a few blocks of Tribeca. Now if only the first were closer to the subway.

Chinatown's cluster exhibited some fine group shows and the busy imaginings of a German artist in her sixties, Rosa Loy (at Lyles & King). Tribeca's best included an entire foam-rubber army by Serkan Ozkaya, a telling assault on white standards of beauty by Ruben Natal-San Miguel, and dark memories of home by Serena Stevens (all at Postmasters). It included, too, eclectic figuration and abstraction by Anna Ostoya and Rebecca Morris (both at Bortolami), nature still vying with color-field painting for Joan Snyder at age eighty (at Canada), and the gender provocations of Clarity Haynes (at Denny Dimin). As you can see from my choices already, so much of the year's best came from blacks and women. Put it down to experienced artists or to an increasing demand for diversity. Put it down as well to a year of change and struggle.

Among other older women back in the galleries, Mernet Larsen bridges early Soviet abstraction, contemporary disappointments, and science fiction (at James Cohan). Mary Frank held up both on her own and in a pairing with Charles Burchfield (at D. C. Moore). African American art of particular interest included portraits by Benny Andrews (my own favorite of the year, at Michael Rosenfeld), kite-like constructions by Sanford Biggers (at the Bronx Museum), more dizzying geometries from Odili Donald Odita (at Jack Shainman), Kara Walker drawings (at Sikkema Jenkins), a southern journey by Kevin Beasley (at Casey Kaplan), and a serious housecleaning of a solemn, upscale dealer from Theaster Gates (at Gagosian). The Shed might have done better by Howardena Pindell, fine as she was, but this is after all the gaudy, depressing Hudson Yards. And who knew that Romare Bearden (at D. C. Moore), the doyen of collage and black culture, took abstract art seriously, too?

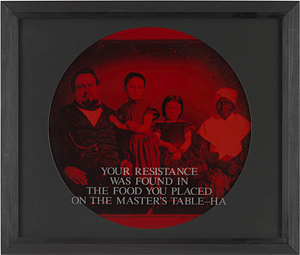

Diversity itself diversified. Black artists also included Africans like Ficre Ghebreyesus (at Galerie Lelong) and Hana Yilma Godine (at Fridman). The first Asia Society triennial is just getting underway. I cannot share in the praise for Kent Monkman (at the Met) or least of all Edgar Heap of Birds (at Fort Gansevoort), but I am learning about Native American art for all that, and Alan Michelson (at the Whitney) could unsettle anyone's certainties. Latinos weighed in as always, with mixed results, like the Puerto Rican print workshop and a Puerto Rican American, Raphael Montañez Ortiz, at El Museo del Barrio (and I shall offer reports soon). The entire year played out alongside Black Lives Matter, and artists both black and white made it a theme.

Diversity is just one story and maybe not the one you most want to hear, in a year when so many voices have been silenced. I would rather look past even these struggles, just as I would rather look past 2020. Another show of political art focused on the prison population, with "An Emphasis on Resistance" at MoMA PS1, and I can only hope for a broader sense of release. I shall not be doing a lot of outdoor dining in the dead of winter. I can, though, hope to see art again one day soon, maybe even without having to make an appointment. And then, slowly, I can start to forget.

Of course, this site has reviewed pretty much all this and more at length. I did not review Kara Walker at Sikkema Jenkins through September 30, because of past coverage of Walker's imagery. Other dates and locations appear with fuller reviews, with links here. You can now also see year-end reviews for 2007, 2008, 2009, 2010, 2011, 2012, 2014, 2015, 2016, 2017, 2018, 2019, 2021, 2022, and 2023.